April 13, 2015: 65ºF, 11:40am-2pm with low tide at 12:30, sunny and warm, not much wind. One loon and two or three crows.

April 13, 2015: 65ºF, 11:40am-2pm with low tide at 12:30, sunny and warm, not much wind. One loon and two or three crows.

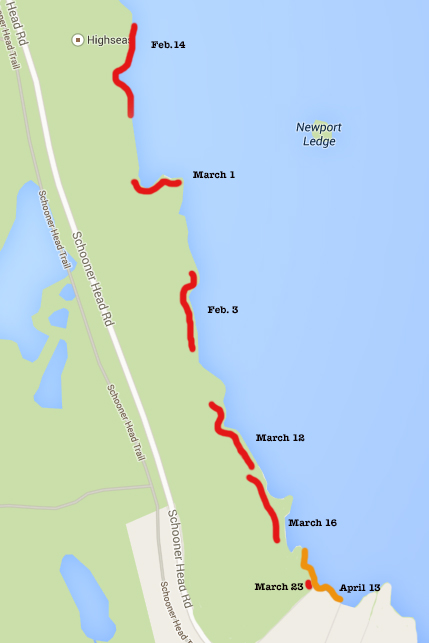

Coast Walk 6: Feb.3 through April 13. That wasn’t so bad – it only took 9 weeks to go about half a mile (not counting trekking in to the shore and back out again.)

The weather changed abruptly this week. And by abruptly I mean it feels like we went from mid-winter to early summer, skipping spring entirely. Last Monday I canceled the Coast Walk because a disgusting mix of snow, sleet, and rain was falling out of the sky and I was pretty sure the shore would still be covered in waterfalls of ice. Today it was 36ºF when I went out at 6am, but by the time low tide rolled around it was sunny and 65º.

As soon as I left the house I had to strip off my coat and fleece, which led to the first problem of the new season: where to put all the things I’ve been carrying in my coat pockets! Clearly I will have to buy pants with enormous pockets or get some kind of fanny pack, because it is a royal pain to pull my backpack off every time I want a tissue. And I don’t dare carry my iPhone in my back pocket – the ice may be gone, but the rocks are still covered in slippery green algae. And in barnacles, which turned out to be the second wardrobe-related issue of the day. This was my first day out without gloves, and scrambling over barnacle-encrusted outcroppings with bare hands was quite painful. I managed not to cut myself this time (barnacle scrapes hurt more than paper cuts and they usually get a little infected) but next time I’ll have to bring a pair of fingerless biking gloves. Mine have padded palms which will be very helpful, although I suspect they won’t last long. Wonder how many pairs I’ll need to get through the summer? Ditto for jeans: my poor snow pants are held together with gaffer tape after 3 months of sliding over ice and barnacles.

I trekked in to the same point that I finished the last post with, just at the northern edge of Schooner Head, but this time I was able to scramble down the low cliff. It was about six or seven feet high, and I jumped the last three feet, thinking that once upon a time when I was ten I used to get a swing going six feet in the air and jump off because it felt like flying. When did a little three-foot jump start to feel scary? Anyway, I headed north to see how much I could reach of the areas I missed while hiking along the top of the cliff.

I trekked in to the same point that I finished the last post with, just at the northern edge of Schooner Head, but this time I was able to scramble down the low cliff. It was about six or seven feet high, and I jumped the last three feet, thinking that once upon a time when I was ten I used to get a swing going six feet in the air and jump off because it felt like flying. When did a little three-foot jump start to feel scary? Anyway, I headed north to see how much I could reach of the areas I missed while hiking along the top of the cliff.

According to my map (The Bedrock Geology of Mount Desert Island), this whole area is part of the shatter zone, which is where the volcano that became Cadillac Mountain pushed through the existing bedrock before the glaciers came, so long ago it makes my brain hurt to imagine it. [My husband proofread this post, and he asked why it’s called the shatter zone. I was like, “Geez, how do you not know that? Oh, right, you didn’t chaperone the 6th grade field trip to Great Head. Twice.” According to the park ranger who led our group (and yes, how amazing is it that our kids go on field trips led by National Park Rangers?) the shatter zone is the very large zone around the perimeter of that ancient volcano where the magma pushed up through the bedrock and shattered it. When we reach Great Head I’ll show you zones where the bedrock floated in the magma until it cooled, and you can see shattered chunks of it embedded in the granite.] There were some really odd bits of rock down there:

That sea stack looks a lot like Bar Harbor Formation stone (which you can see off the Shore Path by the Bar Harbor Inn.)

That sea stack looks a lot like Bar Harbor Formation stone (which you can see off the Shore Path by the Bar Harbor Inn.)

Most of the shore was pretty steep, with lots of these little gullies cutting into the stone. It made for a lot of climbing up and slithering down. You can see how thick the barnacles are, too. Definitely adventurous terrain!

Most of the shore was pretty steep, with lots of these little gullies cutting into the stone. It made for a lot of climbing up and slithering down. You can see how thick the barnacles are, too. Definitely adventurous terrain!

The barnacles were not only dense, covering the surfaces completely, they were really tall, probably because they were packed in so tightly. I suspect that bare patch was opened up by ice forming and then getting pulled off by the waves.

The barnacles were not only dense, covering the surfaces completely, they were really tall, probably because they were packed in so tightly. I suspect that bare patch was opened up by ice forming and then getting pulled off by the waves.

One of the gullies opened out into a small cobble beach under a massive overhang that was almost a shallow cave. Almost.

One of the gullies opened out into a small cobble beach under a massive overhang that was almost a shallow cave. Almost.

It was so nice to see the tidepools without a crust of ice. Seaweed was actually moving around, as were the periwinkles, and I saw the first scud swimming. I couldn’t get a clear photo, sorry; they are tiny and they move so fast, it’s like trying to photograph a toddler on Christmas morning:

It was so nice to see the tidepools without a crust of ice. Seaweed was actually moving around, as were the periwinkles, and I saw the first scud swimming. I couldn’t get a clear photo, sorry; they are tiny and they move so fast, it’s like trying to photograph a toddler on Christmas morning:

Isn’t she cute? Scud are crustaceans, related to shrimp, wood lice, and lobsters, kind of in the way I’m related to my great-grandmother’s sister’s children – distant branch of the same family. Scud and shrimp, for example, are both Malacostraca, which is a class of crustaceans, but scud are Amphipods and shrimp are Decapods. The ‘pod’ in the name comes from the Greek word for foot, and amphipods (translates as ‘different feet’) have two different types of legs, while decapods (translates as ‘ten feet’) have, you got it, ten legs. Scud have seven pairs of leg-ish appendages, so you’d think they’d logically be called septapods, but the legs aren’t all the same and then there are two more leg-ish things that are sort of mouth parts, so it was probably too complicated to explain all that in a made-up Greek-based word. Malacostraca also comes from the Greek and translates as ‘soft shell,’ although as Wikipedia points out, they are only soft after moulting. Thank you, Wikipedia. You’ll have noticed that all the Latin names (aka scientific names) in this paragraph are Greek. They’re called Latin names because the grammatical structure is based on Latin, regardless of what language the name draws from. Scientific names looked pretty uniform when all the people naming things were European, but it makes for some interesting juxtapositions now that science is more inclusive and the base language is, say, Inuit (Tiktaalik roseae, for example.)

Isn’t she cute? Scud are crustaceans, related to shrimp, wood lice, and lobsters, kind of in the way I’m related to my great-grandmother’s sister’s children – distant branch of the same family. Scud and shrimp, for example, are both Malacostraca, which is a class of crustaceans, but scud are Amphipods and shrimp are Decapods. The ‘pod’ in the name comes from the Greek word for foot, and amphipods (translates as ‘different feet’) have two different types of legs, while decapods (translates as ‘ten feet’) have, you got it, ten legs. Scud have seven pairs of leg-ish appendages, so you’d think they’d logically be called septapods, but the legs aren’t all the same and then there are two more leg-ish things that are sort of mouth parts, so it was probably too complicated to explain all that in a made-up Greek-based word. Malacostraca also comes from the Greek and translates as ‘soft shell,’ although as Wikipedia points out, they are only soft after moulting. Thank you, Wikipedia. You’ll have noticed that all the Latin names (aka scientific names) in this paragraph are Greek. They’re called Latin names because the grammatical structure is based on Latin, regardless of what language the name draws from. Scientific names looked pretty uniform when all the people naming things were European, but it makes for some interesting juxtapositions now that science is more inclusive and the base language is, say, Inuit (Tiktaalik roseae, for example.)

P.S. The Latin name for ‘Latin names’ is ‘binomial nomenclature.’

That reddish seaweed in the tidepools puzzled me. I’m not great with seaweed identification, but I’m pretty sure I’ve never seen that before. It also blanketed the rocks in a thick red mass down at the low tide line. After doing some research, I think it’s Dumontia contorta (also known as Dumontia incrassata .) It doesn’t seem to have a common name, although all the sources I found say it’s common in the intertidal zone. The bright green mats of seaweed stumped me. It could be Acrosiphonia arcta, or it could be Ulva intestinalis, or it could be something else entirely. I’ll have to look at it more closely next time I run into it. Sometimes it’s hard to know what to pay attention to when I’m out there.

That reddish seaweed in the tidepools puzzled me. I’m not great with seaweed identification, but I’m pretty sure I’ve never seen that before. It also blanketed the rocks in a thick red mass down at the low tide line. After doing some research, I think it’s Dumontia contorta (also known as Dumontia incrassata .) It doesn’t seem to have a common name, although all the sources I found say it’s common in the intertidal zone. The bright green mats of seaweed stumped me. It could be Acrosiphonia arcta, or it could be Ulva intestinalis, or it could be something else entirely. I’ll have to look at it more closely next time I run into it. Sometimes it’s hard to know what to pay attention to when I’m out there.

Eventually I ran into a part of the shore that said very clearly, “You shall not pass:”

Eventually I ran into a part of the shore that said very clearly, “You shall not pass:”

so I turned back toward Schooner Head, where the cliff drops down to a very pretty cobble beach.

so I turned back toward Schooner Head, where the cliff drops down to a very pretty cobble beach.

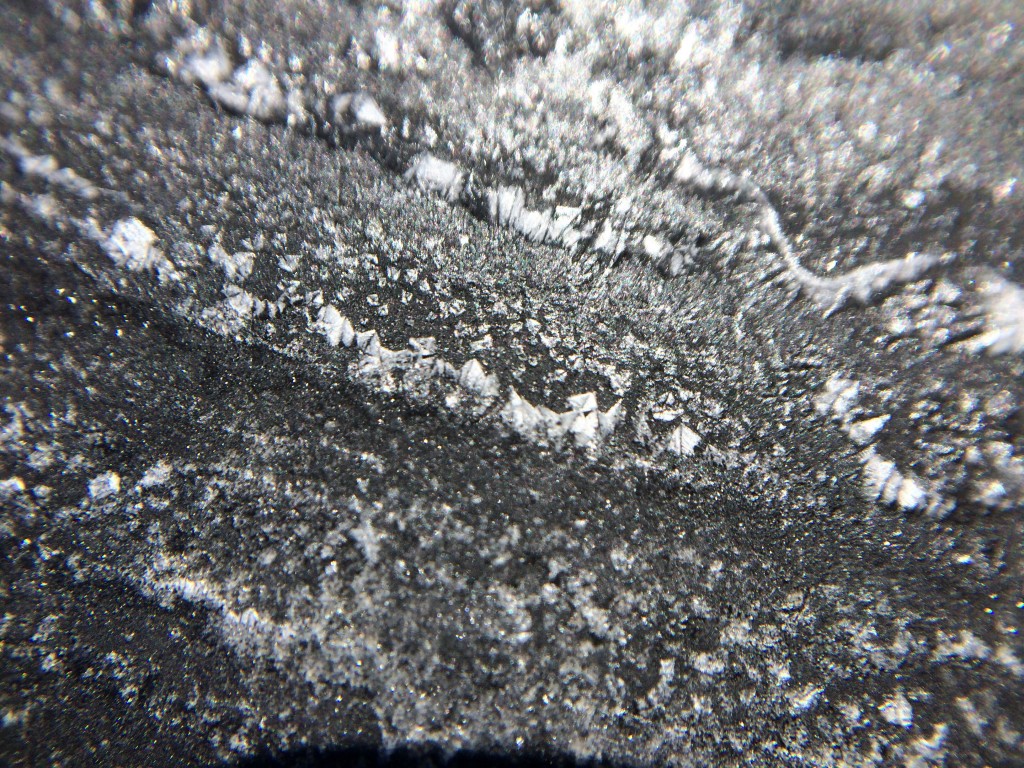

This cobble had a shallow depression worn into the top, which had filled with seawater. As the water evaporated, it left rings of salt crystals around the puddle.

This cobble had a shallow depression worn into the top, which had filled with seawater. As the water evaporated, it left rings of salt crystals around the puddle.

If you come on a Coast Walk with me, be prepared to squat on a stony beach and watch water evaporate. And maybe afterward we’ll go for a cup of coffee and watch paint dry.

If you come on a Coast Walk with me, be prepared to squat on a stony beach and watch water evaporate. And maybe afterward we’ll go for a cup of coffee and watch paint dry.

Closeup of the salt rings (taken with a macro lens on my iPhone):

And with that, I was on Schooner Head, and had passed out of the park boundaries. Thank you Acadia, it’s been wonderful! See you on the other side (of Schooner Head.)

And with that, I was on Schooner Head, and had passed out of the park boundaries. Thank you Acadia, it’s been wonderful! See you on the other side (of Schooner Head.)

P.S. I had permission from the landowner to be here, don’t worry!

Pingback: Coast Walk 11: Part 1, The Inner Cove | The Coast Walk Project

Pingback: Coast Walk 13: Hunters Beach to East Point, Seal Harbor; Part 5 – The Coast Walk Project