July 31, 2015: 4:41-7:30pm, 85ºF, light breeze from mouth of cove, a few puffy cumulus clouds in deep blue sky. Grasshoppers, no-see-ums, bald eagle, green crabs, at least 14 dead Moon Jellies (Aurelia aurita), Sand Shrimp (Crangon septemspinosa), 4 dead and 1 live Rock Crabs (Cancer irroratus), 3 herring gulls, 4 crows; heard 2 chickadees and a loon but didn’t see them.

Some of my posts take you to places you wish you could see but can’t reach without scrambling down cliffs, or along private properties you can’t walk without permission from the owners. This one takes you someplace you’ve never wanted to go: it’s the first mudflat of the Coast Walk! I know I’ve driven past the Inner Cove many times and it looked so unappealing: squishy and buggy and boring. Come on, let’s take a closer look…

It was a gorgeous, hot, late afternoon when I parked at the fish house landing and headed toward the causeway. I last walked through here in late May and the change in traffic was impressive. In May I had the place to myself, but in July the causeway was lined with cars and there were beachcombers everywhere. I knew it was irrational, but I found myself resenting them anyway. After the long, solitary winter it still seems strange to find the shore so crowded. When I crossed the causeway and climbed down onto the mudflats, though, I was alone again. I can’t imagine why the tourists weren’t swarming on this side:

Look how clean and white those sneakers are! You’ll see how long that lasted … The upper edges of the cove were filled with grasses and sedges and several large patches of these two plants: on the left is Sea Plantain (Plantago maritima) and on the right is Sea Blite (Suaeda maritima). I see them a lot along the high tide line and in the spray zone.

It was very quiet as I moved down into the empty cove: I could hear water trickling from all directions and the occasional bubble popping in a puddle. Walking across the flats there were sign of worm-life everywhere. I wish I knew more about marine worms; if only one of my mud-flat-loving friends could have come with me.

The mud in this area was solid enough to walk on (mostly), so I hung out for a while by the edge of the stream of brackish water trickling through the east side of the mudflats. It was full of life – periwinkle grazing, tiny crabs, translucent sand shrimp, and a lot of tiny shrimp-like things that I couldn’t see properly. [If you come on a Coast Walk with me, be prepared to squat for 20 minutes watching practically-invisible half-inch-long translucent things whizz around in puddles while mud oozes into your sneakers.]

This is a Sand Shrimp (Crangon septemspinosa):

It’s in the very center of the photo. Maybe this will help:

Better? Full disclosure: I had no idea what these were, so I posted the photos on Facebook and a bunch of my better-educated friends set me straight.

There were crabs of all kinds, from the size of my pinkie nail to the size of my palm. At the time I thought they were all Green Crabs, which was depressing, but looking at my photos I see at least two other species. I think this one might be a rock crab, but can’t quite tell – it was smaller than a periwinkle! And underwater, too.

Eventually I got a cramp and had to start moving again. The mud quickly got too squishy to walk on so I moved a little higher on the shore where it was rockier. I wasn’t trying to keep my feet clean; hoping to hike a mudflat with clean feet would be kind of delusional, but have you heard the term ‘honeypot?’ It’s a wetter, stickier area in a mudflat that you find mostly by stepping into it and finding you can’t step out. I was hiking in sneakers [still hadn’t bought proper boots to replace my deceased pair], and I was trying to avoid losing them in the mud.

The rockweed that had been exposed by low tide was pale brown and dusty looking, covered in what I think was dried silty clay that must have been stirred up by the tides, suspended in the water, and deposited as the tide receded:

A whole swarm of Moon Jellies (Aurelia aurita) had washed up in the rockweed. I counted 14 in this patch – all sizes from softball up to dinner plate.

See those four white things in the jellyfish? Those are its gonads. Jellyfish don’t have a lot of internal structures – the part we think of as the ‘jelly’ acts as their lungs and their digestive system (it’s called the “gastrovascular cavity“) and they don’t have a circulatory or excretory system (no blood or poop) – but they do have a reproductive system. Those moon jellies have very clear priorities.

Also notice the crust of mud beginning to creep up around the edges of my sneakers.

Those “bugs” on the jellyfish are springtails. Remember way way back on Schooner Head when I lectured you about decapods and amphipods and Latin names based on Greek adjectives? So springtails are hexapods. Hexapods were once considered insects but are now their own separate thing, which is why I had to put quotations on the word ‘bugs.’ Hexa comes from the Greek word for six and pod comes from the Greek word for foot, so yeah, the hexapods have six legs. Just like bugs! But they’re not bugs because science. There are a lot of different species of springtails (“a lot” is shorthand for “I couldn’t find a specific number”) and Wikipedia estimates there are 100,000 individuals per square meter of ground anywhere on earth where there is soil. Let’s pause to consider that. Different species have adapted to different environments – you’ve probably seen snow fleas in the winter? Those are springtails, too.

These particular springtails are Anurida maritima, a species adapted to the intertidal zone. You often see them in masses on the surface of tidepools. Their bodies are covered with hydrophobic hairs that let them move around on top of the water. (Hydrophobic in this case is a chemistry term meaning the hairs effectively repel water.) Here they are performing their function as scavengers, helping break down organic matter (aka dead jellyfish).

The shore started to get rockier, and I found animal scat on top of the stones, out in the open, just above the high tide line. Again! Wish I could figure out what animal does this. There were several piles of similar shape but with varied content – one was white and seemed to be mostly thin shell fragments like crab carapaces, another was dark and appeared to have seeds in it, and the third

was brown and full of stuff that looked like insect bodies. Maybe chitin is indigestible?

Jumping from decomposing jellyfish to macro photos of poop – are you thoroughly grossed out yet?

You’re welcome.

[Nov.29, 2015 – Pretty sure it was either otter or racoon scat.]

Just past the poop, the shore was covered with old quarry stones,

which must be the location of Ans’ Wharf on this map:

detail of “The Village of Otter Creek,” hand-drawn map by Karen Zimmerman. Available here. This is a great map if you are curious about Otter Creek history. Karen is a graphic designer who lives in Otter Creek and has become sort of an unofficial historian of the town. This is only a little bit of the map, and the rest of it is just as packed with interesting tidbits. My favorite is the midwife’s house: “over 75 babies born here!”

Ans’ Wharf is named for Ansel Davis, who fished out of the cove in the 20th century. Davis’ house was up the hill from the wharf. He also had a fish house next to the Walls fish house we saw on the east side of the cove (labelled “fish houses were here” on the map.)

The wharf was originally built in the 1870s for Cyrus Hall’s first quarry on MDI. Yes, the first “Hall’s Quarry” on the island was here in Otter Creek! So was the second (across the cove on the west side.) The town we currently know as Hall Quarry, over on Somes Sound, was Hall’s third venture, begun in 1883. You can see the first quarry on this 1887 map:

Cyrus James Hall was born outside Belfast (Maine, not Northern Ireland) in 1834, taught school for a while, then started a lumber and granite business in Belfast. We’ll talk a lot more about Hall when we reach Hall Quarry, but various sources describe him as well-dressed with scholarly interests, but tough and hands-on in the quarry.

Hall came to MDI looking for a better grade of stone, and settled on the distinctive pink-red granite of Otter Creek. He formed the Standard Granite Company in 1870, and the Otter Creek quarry began production in 1871. Eventually Hall recruited experienced stonecutters and quarry men from Italy, Scotland, Finland, and Sweden, and Otter Creek became a bustling commercial center, sending granite all over the East Coast. OC granite was also used in the Northeast Harbor Episcopal Church.

I’ve been hunting for old photos for several weeks (one reason this post has taken a month to write) but the photo below is the ONLY one I could find of Otter Creek Cove during the quarrying period, and nobody seems to know who took it or when. I struck out finding anything else at the MDI Historical Society, the archives of the Northeast Harbor Library, and even the Maine Granite Industry Museum!

In this early photo of Otter Creek Cove, a schooner is docked at the approximate location of Jimmy’s Wharf on the west shore. A fish house is visible on the east shore. Image courtesy of the Northeast Harbor Library.

I can’t see it in the photo, but apparently the shoreline was full of quarry-related structures: wharves, roads, derricks, pens for the oxen who pulled the loads of granite around, and so forth. According to Deur (source listed below) “Hall’s men constructed wharves from natural rock ledges … on either side of Otter Creek cove. Modern residents refer to the initial wharf constructed on the eastern side as “An’s Wharf,” while the wharf for the quarry on the western side was called “Jimmy’s Wharf.” A third wharf, Grover’s Wharf, operated near the west-side fish houses for a time… . Shipping of granite was, at best, difficult from this small and shallow cove… . Ships loading granite from the quarries commonly were allowed to become grounded at low tide, were loaded in this condition, and then floated free with their loads on the rising tides… . During the quarrying, ships filled Otter Creek. At times, there were ships at both An’s Wharf and Jimmy’s Wharf simultaneously. At other times, ships were aligned to fill the bay from one wharf to another – perhaps in an effort to minimize listing of ships while they were loaded at low tide. As explained by Norm Walls, ‘all the way across Otter Cove on the inside of [what is now] the Causeway. My grandmother…told me that she could [practically] walk from this side to the other side across boats. They would be tied up in there waiting to get loaded with stone.’ ”

Otter Creek granite was not only distinctively colored, it was one of the hardest stones quarried in Maine. The hardness of the stone, which wore out tools and slowed work, and the difficult harbor limited the production possible in the quarry. (Deur again:) “Drills and other tools had to be sharpened and repaired almost constantly. … Even when operating at breakneck speed, an entire tidal cycle was required to load a ship with granite, and typically only two ship loads of stone could leave the cove per day.” Once he opened the quarry on Somes Sound, Hall sold off his Otter Creek property to smaller companies. “Comparatively small-scale quarrying operations persisted, some under the direction of J.S. Salisbury. Salisbury resumed some of Hall’s aggressive marketing of the distinctive Otter Creek granite, successfully selling numerous loads to builders in Boston and other Northeast cities through the late 19th century, though production at the quarries tapered off considerably by the late 1880s. … Salisbury maintained quarrying operations until the beginning of the 20th century. After that time, the quarries were largely disbanded, with small-scale quarry operations emerging occasionally for local stone projects.”

[Sources for the above include C.V. Truax, “The Pink Granite of Somes Sound,” Downeast Magazine, Oct 1972; Douglas Deur, The Waterfront of Otter Creek: A Community History, National Park Service, 2012; Steve Haynes, Maine Granite Industry Historical Society website, and 2 unpublished manuscripts in the collection of the MDI Historical Society.]

At the risk of making this post unreadably long, I have to tell you about the Maine Granite Industry Museum.

As I read through the chapter about the quarries in Deur’s book, I kept coming across quotes from Steve Haynes, so I did a little research and found he is the guy behind this museum. It’s on the Beech Hill Crossroad in Somesville, and I’ve driven by it a few times over the years, always thinking I should stop and have a look, but of course I was always in a hurry to get somewhere and then forgot about it as soon as it was out of sight. You know how things go. Well, damn, but I had missed out! This place is amazing. It’s not big and it’s not fancy, but it sure is comprehensive. The walls are covered with historic photos of quarries all over Maine, and photos of the people who owned them and worked in them. Steve has been interviewing former quarry workers for years, and man, would I love to go through his archived material. He’s working on a book, so one of these days we’ll all get to read it.

As I read through the chapter about the quarries in Deur’s book, I kept coming across quotes from Steve Haynes, so I did a little research and found he is the guy behind this museum. It’s on the Beech Hill Crossroad in Somesville, and I’ve driven by it a few times over the years, always thinking I should stop and have a look, but of course I was always in a hurry to get somewhere and then forgot about it as soon as it was out of sight. You know how things go. Well, damn, but I had missed out! This place is amazing. It’s not big and it’s not fancy, but it sure is comprehensive. The walls are covered with historic photos of quarries all over Maine, and photos of the people who owned them and worked in them. Steve has been interviewing former quarry workers for years, and man, would I love to go through his archived material. He’s working on a book, so one of these days we’ll all get to read it.

He made this map showing all the quarries he’s documented on MDI:

There’s a stone sample for each quarry:

Steve has located the old quarries on the map with samples of the stone. It was fascinating to see how the color and texture of the granite changed from place to place. But wait, there’s more.

He showed me the tools the workers used to quarry stone (yes, he’s collected historic tools, too.) You know how my mind gets boggled at least once on most Coast Walks? This was the moment. See the squarish hammer and the long piece of iron lying on the table at the right? When books talk about “drilling” in the old quarries, well, that’s the drill. One guy would hold the iron rod at the point where they wanted to make a hole, and another guy would whack it with the hammer. Hard. Then the first guy would turn the rod slightly, and the second guy would hit it again. Turn, hit, turn, hit. Eventually they would have a hole. You say the word “drill” and I picture a machine. Something with gears, at any rate. Not two guys and a piece of iron! Every single building ever built before, what, the 1880s? – the stone came out of the ground like that. One whack at a time. At least in the 19th century they could put blasting powder in the holes.

These are tools for finishing the stone – splitting it, adding a texture to the face, or polishing it. I’m sorry I didn’t get a closer picture of this, but see the gray rectangle of stone on top of the granite block at left? That’s emery. Steve said emery has been quarried in Greece for thousands of years. It is about a 9 on the Mohs scale (diamond is a 10) and is used for polishing stone. Like this: you take that block of emery and rub it against the granite for a few hours. There’s a technique to it, obviously, but that’s what it comes down to. Patience. Steve has samples of stone from all the quarries he’s documented. You can kind of see them on the tables around the walls in the top photo. He polished every one of them by hand. I’m just going to pause for a minute while we think about the time and labor involved.

These are tools for finishing the stone – splitting it, adding a texture to the face, or polishing it. I’m sorry I didn’t get a closer picture of this, but see the gray rectangle of stone on top of the granite block at left? That’s emery. Steve said emery has been quarried in Greece for thousands of years. It is about a 9 on the Mohs scale (diamond is a 10) and is used for polishing stone. Like this: you take that block of emery and rub it against the granite for a few hours. There’s a technique to it, obviously, but that’s what it comes down to. Patience. Steve has samples of stone from all the quarries he’s documented. You can kind of see them on the tables around the walls in the top photo. He polished every one of them by hand. I’m just going to pause for a minute while we think about the time and labor involved.

And then we’ll get back to the mudflats. The shore got progressively steeper as I moved north toward the creek mouth. I don’t know when the stone was put there, but it all seems to be quarried, so I’d guess it’s been there a while:

I had a moment of humility right here but I didn’t know it until I got home. You know how I’m all ‘I’m an artist, I’m so observant, I’ll show you cool places and things you haven’t seen?’ Well! I was trying to photograph the gulls flying around, but I was shooting into the sun and couldn’t really see what I was shooting. None of those photos came out well – surprise – but when I looked through them on my computer I found this:

A bald eagle had been watching me the whole time.

After not-seeing the eagle I saw this:

A skeleton out in the middle of the flats.

What do you think – small deer? Medium size dog? No skull anywhere, sorry.

By now I was getting really close to the mouth of the creek and the shore was flattening out. The alders dipped so low over the cove there was rockweed tangled in their branches.

Looking back toward the causeway from the mouth of Otter Creek:

What’s that you say, it looks like an empty swimming pool? Funny you should say that. I’d heard John D. Rockefeller, Jr. wanted to make this a swimming area when he had the causeway built, so I did a little research and found some interesting info. [The quotations and most of the info that follows come from Otter Creek Cove Bridge and Causeway, Richard H. Quin & Neil Maher, Historic American Engineering Record, 1995.] Point one is that Rockefeller didn’t build the causeway. Oh, he built the roads on either side, commissioned the design, and hired Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. to review it, but for some reason he moved on to other projects, and the causeway was paid for by the Park Service and constructed by the Bureau of Public Roads, a government agency that had a contract for building roads in the national parks at the time (and which eventually became the Federal Highway Administration.) The BPR also built the road up Cadillac. Point two is that yes, a number of people thought this would make a good swimming area, and the arches under the causeway were built with slots for boards that would hold the water in the inner cove. (Look at the bottom right corner of the drawing below.) They are still there. The Inner Cove could made into a swimming pool tomorrow. In theory.

The lead engineer on the design was Leo Grossman of the Public Roads Administration, and the contractors were Sammons, Robertson & Henry, of Huntington, West Virginia, and J. M, Francesea & Co. of Fayetteville, West Virginia. I have to admit, when I read that they’d brought contractors in from Away, I thought, ‘and what were the local builders, toast?’ I mean, the quarry just up the hill had only been closed for maybe fifteen years.

The HAES survey had a ton of technical detail, and I was tempted to quote the whole thing, but I guess I’ll take pity on anyone who doesn’t care about the relative cost of a bascule bridge as opposed to masonry-faced earthwork. If you want to geek out you can find the full report here. The report summarizes the causeway’s construction method: “The entire structure is 215′ in length with a bridge span of 62′. The middle of the three arches is 15′ wide while the two side arches are each 12′ wide. The structure is constructed atop a natural bar which extends nearly across the upper part of Otter Creek Cove. It features a concrete core wall through part of the bar to prevent water from undermining it; otherwise the bridge is of nearly solid masonry construction. This contrasts with the other bridges on the system, which are generally reinforced concrete bridges faced in native granite. In this case, stone construction was adopted because of fears that salt water would cause deterioration of a concrete structure. The central or “bridge” section of the structure is comprised of solid stone masonry arches. These are covered with a Class A concrete backing, troweled smooth, over which there is a waterproofing membrane. Above this is a level of stone or gravel sheathing, and then a compacted earth fill between the arches and the spandrels. Above this is a standard bituminous asphalt roadway surface. The Otter Creek Cove Bridge and Causeway is essentially a filled spandrel arch bridge with causeway extensions to either side.”

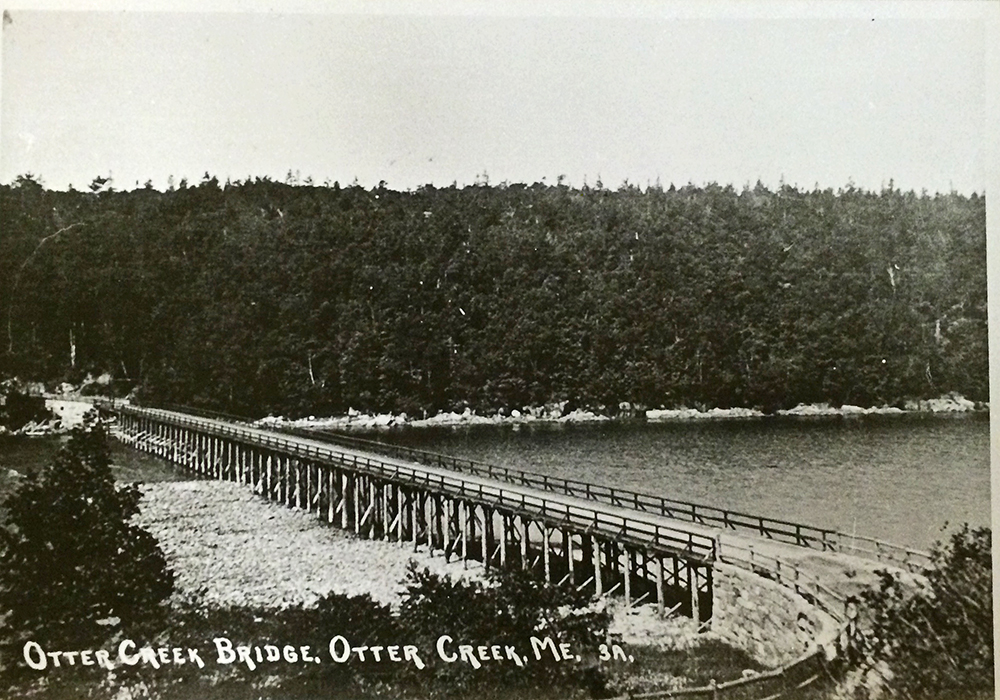

There were several prior attempts to build a bridge across the cove, beginning in the late 1880s. All of them were destroyed in storms. Sometime after 1913, Hancock County finally built one that lasted more than a few months. “This structure was 625′ long and consisted of a 555′ wooden trestle bisected by a 70′ pivoting swing bridge. The central stone-filled crib pier of the swing bridge was bordered on either side by two 30′ channels, while the ends of the swing spans rested on granite abutments. The connecting trestle, standing some 22′ above the water level, was constructed on the north end on a natural bar composed of sand, cobbles and boulders thrown up by the sea.”

You can see the existing bar in this photo – looks like it ran halfway across the cove. Image courtesy of the Northeast Harbor Library

The swing-span of the bridge began to fall apart by the 1920s, when Rockefeller was working on the Park Loop Road plans. “In August 1925, Rockefeller employed the J. G. White Engineering Corporation of New York to inspect both the cove and the old swing-span bridge. The firm reported that the bridge’s trestle, although in a “considerably decayed” condition, was nonetheless intact though the swing-span had disappeared. The central pier remained, although it too was in a dilapidated state. … The bar across the cove was described as approximately 500′ long at low tide and 350′ wide, and the creek channel was measured as 55′ wide and 4′ deep.”

“… The J. G. White report recommended that the new bridge should be constructed immediately south or seaward of the existing trestle and bridge. The natural bar, the report suggested, would offer protection for any structure built upon it. … In the fall of 1925 the company conducted a second series of surveys and borings and reported in December on physical conditions at the site. … Borings in the channel bar revealed its composition as a 1′ layer of cobbles and small boulders underlain by 4′- 8′ of sand which rested on soft blue clay. Beneath the channel itself, rock was struck at depths ranging from 2′-14′. While most of the rocks had probably been deposited by storm tides, a granite ledge was clearly evident about 12′ beneath the trestle’s west abutment and served as its foundation.”

“The White Engineering Corporation [proposed] a “causeway-dam.” … This option would also feature a spillway near the middle of the structure… . The spillway would ordinarily be closed with stop logs to an elevation of about 1′ below high tide. This would trap sea water behind the structure, creating a pond or pool which could be used for swimming. The stop logs could be adjusted for height of tide, or to adjust clarity or levels of salinity. The depth of the “pool” would range from 0′ at the shore to about 14′ in the channel. … The company again suggested that if a dam were to be constructed it would be necessary to obtain all riparian rights above the structure, and the permission of the War Department would have to be secured for any structure as the cove was technically an historically navigable body of water. …”

“Over the next four years, Rockefeller’s chief local concern was the extension of his comprehensive carriage road system and the continuation of work on the park motor road system which ultimately evolved into the Park Loop Road. In 1930, he engaged noted landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. to study the Otter Creek Cove crossing, and provided him with copies of the J. G. White reports. He evidently told Olmsted that he was interested in the concept of impounding the cove to allow for swimming, as ideas concerning the measure appear in the reports. Olmsted surveyed the cove in March 1930. He agreed with the White Corporation engineers that the road should be built across the bar and not run around the head of the cove far to the north. … Yet whereas the White company’s proposal envisioned the causeway as cutting straight across the bar, Olmsted recommended that it be curved. Olmsted also … recommended lowering the structure about 3′ for “reasons of appearance rather than economy.” A separate channel, he argued, could be constructed for Otter Creek if it was determined that fresh water entering the head of the cove might “pollute” the salt water behind the dam (bacterial growth is hampered by high salinity, while fresh water encourages it). This water in this “scenic pool” behind the dam, Olmsted believed, would warm enough during the summer to permit comfortable bathing while a “much-to-be desired sand beach” could be developed against the outer wall of the raised bar, adding to the pleasure of the bathing pool on the other side. … In conclusion, Olmsted summarized his views on the matter. ‘I would recommend without hesitation the construction of a solid fill causeway across the inner bar for the road-crossing with the incidental formation of a sheltered and sun-warmed tidal bathing pool behind it, as giving both the most agreeable solution of the whole problem from a landscape point of view and one of the least costly solutions that would be reasonably satisfactory.’ [Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., “Special Memorandum in Regard to Crossing of Otter Creek Cove,” March 1930. Acadia National Park Library.]”

“By the mid-1930s, Rockefeller was withdrawing from further work on the park motor road system. Although he financed the construction of the Ocean Drive and Otter Cliffs sections of the Park Loop Road, he ultimately declined to construct the Otter Creek Cove Bridge which would have connected the two segments. The National Park Service turned to the Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) … BPR structural engineers concluded that the causeway should be constructed of dumped rock with large blocks on the outside. Instead of a clay core, they suggested a thin concrete core wall rising only to within a foot of high water, the maximum height thought desirable to hold back tidewater in the basin. Clay, they believed, was liable to erode from tidal ebbs and flows in a loose-jointed rock structure. The openings, which could be closed with stop-logs, should be located in the deepest part of the channel. This would allow small boats without masts to pass through if the openings were left open, negating any legal objections regarding navigation. … Olmsted met with Rockefeller in late November 1935 and secured his acquiescence to these revisions. The Bureau of Public Roads began preparing new plans for the Otter Creek Cove Bridge and Causeway during spring of 1936.”

“In its 1937 appropriation, the National Park Service secured $500,000 for the construction of the Otter Creek Cove Causeway and the adjacent Black Woods section of the Park Loop Road. With the funding assured, Rockefeller transferred the adjacent land to the government so the road project could proceed.”

“To determine the final location for the route across the cove, BPR engineers established a location line approximating the curved top of the bar. Since the bar was composed of rounded stones or cobbles, the top surface of which shifted with the tides, it was necessary to determine if the bar could permanently bear the roadway. The engineers staked a line across the bar from shore to shore, then took borings every 50′ along the line. As they had no power equipment, the engineers acquired a supply of used pipe and used local laborers to drive the pipe to the bottom. Once the information was tabulated, it was decided to construct a long concrete core wall to serve as a spine to prevent the undermining of the structure. Stone riprap would be used to protect the fill on the ocean side since it had also to be placed on a relatively flat slope to minimize damage from the waves. … The structure was completed in September 1939 and the Otter Creek section of the Park Loop Road was opened to traffic. Rockefeller notified Olmsted that the road had been opened and wrote that he was especially pleased with the causeway, stating that it “looks as if it has always been there, so naturally is it related to the surrounding country, while the curve only adds to its beauty.” He added that motorists were delighted with the road, and congratulated Olmsted on his role in the successful design of the structure. Despite the intentions of Rockefeller and his planners, and the provision for stop-boards in the three bridge arches, the structure was evidently never used for impounding waters in the cove. It is very likely the Park Service would have objected to the concept of an artificial swimming basin as inappropriate for a national park and would have ordered the stream flow left unobstructed.”

We now return to our regularly scheduled program.

The sun went behind the hill as I rounded the end of the cove and the temperature dropped about ten degrees. (Not exaggerating: it had been 85ºF when I started at 4:40pm, and was 76º when I reached my car around 7:30.) It’s amazing how cold 76º feels when you are sweaty and tired and in the shade!

There was a surprising amount of industrial debris at the mouth of the creek. I’ve heard engines were sometimes used as moorings:

The mud there and along the west side felt like clay, and you can see how the rocks were covered in a thin coating of it. Now we can add clay to the list of slippery things that cover the rocks I’m walking across (seaweed, algae, and ice so far.) My sneakers were already soaked, so I stood in the channel to rinse off some of the clay:

Just around the curve of the cove’s head I found the Otter Creek town boat ramp:

I never did find the landward entrance to it. There were some pretty waterfalls in a little cove just north of the ramp. You can probably tell from the photos that twilight was falling here on the shadowed side, even though the east side was still brightly lit.

As I got past the muddiest area, I had to get through a stretch of rockweed-covered boulders.

Usually I deal with tricky ground like this by finding cracks or spaces between boulders to brace my feet, or I jam them into crevices. It works well with boots but was really painful with sneakers! By the end my right arch was aching, I was limping slightly, and my left toes all bruised. No more hikes til I get proper gear! Eventually I reached Jimmy’s Wharf (see Karen’s map way way up above).

“Jimmy’s Wharf – A stone wharf formerly used for transshipment of granite from the Hall quarry on the west side of Otter Creek cove. The identity of Jimmy remains unclear, except that this was a resident who used this point for water access at this point following the peak of quarrying in the late 19th century.” (Deur, p.24)

I was slipping a lot by this point, maybe because of the clay and the treacherous ground, but maybe because I was getting tired. I try to be sensible about my limits – it would be SO EMBARRASSING to have Search & Rescue come and bail me out if I sprain an ankle being stupid! I also knew that not far past the wharf the shore turns into sheer granite cliffs right up to the causeway tunnel, so I scrambled up the hill looking for a trail marked on my map.

Found it. Terrible photo, I know – it was really dark in the woods by this time. The path I was on intersected the Quarry Path at its southern end. This is a new trail in Acadia, and is pretty cool:

Found it. Terrible photo, I know – it was really dark in the woods by this time. The path I was on intersected the Quarry Path at its southern end. This is a new trail in Acadia, and is pretty cool:

“The brand-new Quarry Trail and Otter Cove Trail—connecting Blackwoods Campground with Ocean Drive and the Ocean Path through Otter Cove—were opened on National Trails Day, Saturday, June 7th … Visitors camping at Blackwoods can now access the very popular and scenic trails on Gorham Mountain, the Beehive, Champlain, and beyond, without getting in a car nor even walking along the Loop Road. The Quarry Trail … was built using an old road, which dates back to the era when granite quarried in Otter Creek would be loaded onto ships in Otter Cove. Many Otter Creek residents can remember taking the old Quarry Road to the shore for fishing, swimming, or just an enjoyable walk. In the Winter 2013 Friends of Acadia Journal’s “Where in Acadia?” feature, resident Rick Higgins remembered childhood swims from Jimmy’s Wharf as the tide came in, because “the water would be much warmer from the sun beating on the mud flats.” Fifth-generation resident Dennis Smith recalls that some of his first memories are of walking down to the causeway with his babysitter and fishing for pollack—he says he’s “been a fish fanatic ever since.” Smith was interviewed for a Friends of Acadia video about the trail (it can be viewed at vimeo.com/friendsofacadia) in which he noted that his grandfather used the Quarry Road when cutting firewood in the park—an activity frowned on by George Dorr, much to the grandfather’s disgust. Smith chuckled at the memory, recognizing that although past generations had to give certain things up when the park was formed, today’s generations can easily see all that has been gained in return.” [“Old Roads to New Trails,” Thomas & Church, Friends of Acadia Journal, Fall 2014.]

The trail curved down the hill and I limped out onto the causeway, splattered with mud up to my knees, limping and vowing to get a decent pair of hiking boots in the morning. This is beginning to seem normal: the Coast Walks always seem to start out with me chasing random grasshoppers for a good photo and by the end I’m so tired a whale could breach and I might not care.

In the next installment, Karen Zimmerman takes us INSIDE the Otter Cove fish shack. Stay tuned!

Pingback: Notecards are ready! | Jennifer Steen Booher, Quercus Design

The detail and research are thorough and accurate. Thank you for preserving our history. And for sharing Steve Hayne’s knowledge. I have loved his map showing the different granites we have here. A visit to his museum is highly recommended. Your trip through inner cove, my back yard, captures the wealth of cultural and natural history, as well as the simple joy of exploring all the treasures low tide can offer. Glad you did not slip on the clay!

Thanks, Karen! I’ve so enjoyed exploring Otter Creek Cove. I had no idea how much history was hidden there!

fascinating! as an occasional visitor to mdi and mother of the northeast harbor archivist, i came over at her advice, and i will return!

I’m glad you enjoyed it, and Hannah’s awesome!

Pingback: Coast Walk 11: Part 2 – the West Side of Otter Cove | The Coast Walk Project