May 13, 2015: 12:30-3:15pm, low tide at 1:08pm, 63ºF, sunny, strong wind and heavy surf. Cold in the wind, warm out of it. 10 eiders (5 male, 5 female), 2 possible laughing gulls, several Herring Gulls, 1 crow, 1 dead salamander, 2 green crabs (1 dead, 1 alive), 1st live sea urchin of the Walk.

I’m afraid the blog has been falling behind a bit – I’ve reached Hunter’s Beach in real life, but here on the blog we’re still on Otter Point. When I first started working out the logistics of this project, I thought one mile per week sounded reasonable, and based on my previous beachcombing experience, I thought I could go about a mile in roughly two hours. Ha! My usual beachcombing haunts were relatively flat beaches that are good collectors of junk, like Hulls Cove. Now that the ice has melted, I can’t blame my slow pace on winter, and I’ve had to admit that even though I’m getting stronger and faster, scrambling up and down ledges and small cliffs just takes longer.

And when you throw in a good tide pool, some interesting rock formations, and a critter or two, well, the hours just slide by. I’ve kept up the pace of one mile per week by spreading it over the course of several days, but there’s this little matter of earning a living (and raising a family) that’s messing up that plan … I hate to say it, but I’m going to have to slow down. Yes, I know, one mile every two weeks sounds positively lazy, doesn’t it? But going around Otter Point and the east side of Otter Cove took me about 15 hours over the course of 5 days because the tide pools were amazing and I didn’t want to miss anything. Then there were at least 30 hours of editing photos and transcribing audio from interviews, hunting through the Acadia National Park archives, researching critters, searching for old photos, and reading up on the history of Otter Creek … there were so many amazing things in that one mile it’s going to take three blog posts to cover them all!

So here we are, two weeks ago, heading down the Otter Cliff path with my husband, Brian, on a gorgeous spring day, with a strong wind whipping our hair into our faces and waves crashing against the rocks.

The first thing I noticed was the abrupt shift from the angular but rounded pink granite we’ve been walking on since Sand Beach

to the mixed up, sharply broken formations of the shatter zone.

Then I found a dead salamander in a rock pool up near the top of the cliffs and forgot all about geology because I was too busy looking in every pool to see if there were any live ones. (I’ve been hoping for salamanders ever since Rich told me he’d found their eggs in pools here at Otter Point.) Nope, no salamanders.

As we climbed a little further down we found a dozen or so ladybugs scattered across the rocks:

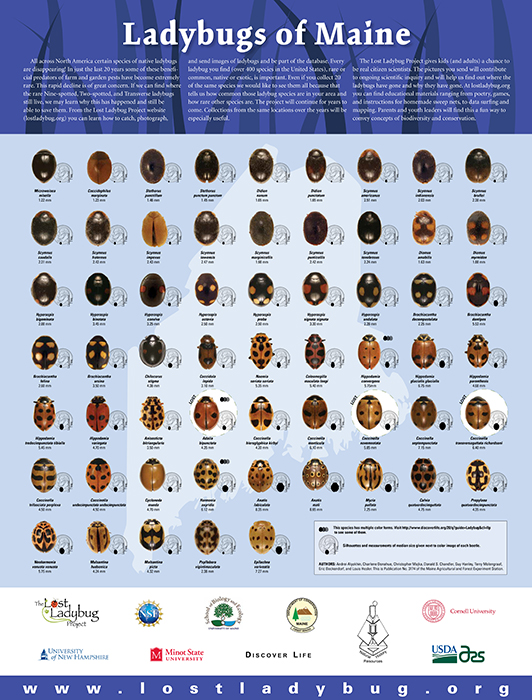

And this is typical of why writing the blog takes so long: at the the time, I just thought, ‘Huh, that’s odd,’ but back home editing the photos I got curious about why ladybugs would be crawling around on granite in the spray zone. They eat aphids, right? And there are no aphids on seaweed. Or rocks. A Google search for “Maine ladybug” brought me to The Lost Ladybug Project and this poster of all the ladybugs found in Maine:

Who knew there were so many species! The LLP is documenting ladybug populations in North America, trying to figure out why native ladybug populations have decreased while imported ladybugs have spread rapidly. “This is happening very quickly and we don’t know how, or why… We’re asking you to join us in finding out where all the ladybugs have gone so we can try to prevent more native species from becoming so rare.” I’m fascinated by other people’s obsessions and a big fan of citizen science, so down the internet rabbit hole I went, trying to ID my bugs so I could add my photos and info to their database, because they asked so nicely.

I was really hoping we had found some Coccinella novemnotata, the Nine-spotted Ladybug (the LLP organizers’ enthusiasm must be infectious because I’ve never thought twice about ladybugs before other than to sweep their dead bodies off my windowsills) but after spending half an hour staring at photos on the Lost Ladybug site, with excursions to Wikipedia, I’m pretty sure our bugs were Coccinella septempunctata, the Seven-spotted Ladybug, which is the most common ladybug in Europe. The species was introduced in the US back in the 70s as a biological control for agricultural pests like aphids. If you remember my rant about Latin names, you might guess that ‘sept’ mean ‘seven’ and ‘punctacta’ means ‘spotted’ (as in ‘punctuation’ and ‘puncture.’)

A few other interesting things turned up: this particular species was the first to be named ‘ladybug’ and all the others were named by association; ladybugs were named for the Virgin Mary (as in “Our Lady); and the seven spots symbolize “her seven joys and seven sorrows,” which is a Catholic thing so I had to look it up. If you are curious, the joys are listed here and the sorrows here. It’s a particularly strange association since ladybugs are not only carnivores (they eat aphids), they can be cannibals, too.

I also discovered that ladybugs have a couple of larval forms, which shouldn’t have surprised me, but it did:

“Ladybird May 2008-1” by Alvesgaspar – Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Oh, and when ladybugs are threatened they bleed from the knees (apparently it tastes and smells bad to predators.) I still don’t know what they were doing wandering around on the shore, although I did read that they like to overwinter in a south-facing spot with tussocks of grass and sheltered by boulders, so maybe they were just waking up from a long winter’s nap.

So, after the ladybugs, we reached sea level, and the tide pools got more and more crowded with seaweeds.

The sun was right overhead, and the glare made it difficult to see under the water and just about impossible to photograph. You can probably tell the photos look a little flat today – that’s the overhead lighting.

The topography alternated between ledges stretching out into the sea

and bouldery areas completely carpeted with rockweed.

There were even a couple of stretches of our old friend, the Bar Harbor Formation.

We saw the first live sea urchins of the Walk, but I couldn’t get a decent photo of them. They were too far down and the glare was too bright. On our way back up the cliff we spotted something moving in this tide pool:

We saw the first live sea urchins of the Walk, but I couldn’t get a decent photo of them. They were too far down and the glare was too bright. On our way back up the cliff we spotted something moving in this tide pool:

Several somethings, really. They were black, fish-shaped, a couple of inches long, and moved very fast. We climbed back down to get a better look but the somethings promptly hid. We waited patiently for about ten minutes, but they were stubborn and we went home without seeing them.

Several somethings, really. They were black, fish-shaped, a couple of inches long, and moved very fast. We climbed back down to get a better look but the somethings promptly hid. We waited patiently for about ten minutes, but they were stubborn and we went home without seeing them.

In other news, the pile of things I found back on Coast Walk 3 is on the light table, and the next still life is starting to take shape.

Take your time. It’s not a race. I love every minute of it. 😉