Looking back at Asticou Landing and Terraces from the dock.

The Coast Walk is entering an experimental phase. I mentioned in my last post that I received a Kindling Fund grant this year to help with the cost of transcribing interviews. Usually I talk to people while we are hiking a section of coast, and then write an essay weaving that discussion around the photos and narrative of the walk. Well, I need to use up my grant money by the end of the year, and that won’t happen with my current pace of obtaining permissions for these hikes (about 6 months per mile) so I’ve started interviewing people like mad, wherever and whenever they are willing to meet. I’m going to present the interviews to you as they happen, and tie them back into the Coast Walks when I pick up that thread again.

Rodney Eason, CEO of the Land & Garden Preserve, was good-natured enough to be my first guinea pig volunteer. The Preserve manages the Asticou Azalea Garden, the Thuya Garden and Lodge, the Asticou Terraces (which some of us call “the path up to Thuya”) and the Asticou Landing (also known as “the Thuya Dock.”) As of this year, they also manage the Little Long Pond area. Rodney and I met at the Asticou Landing at 3pm on September 29, 2017. It was 65ºF (18ºC), sunny, with a light wind from the mouth of the harbor: a gorgeous late-summer day. He had brought a handful of photos from the Thuya archives.

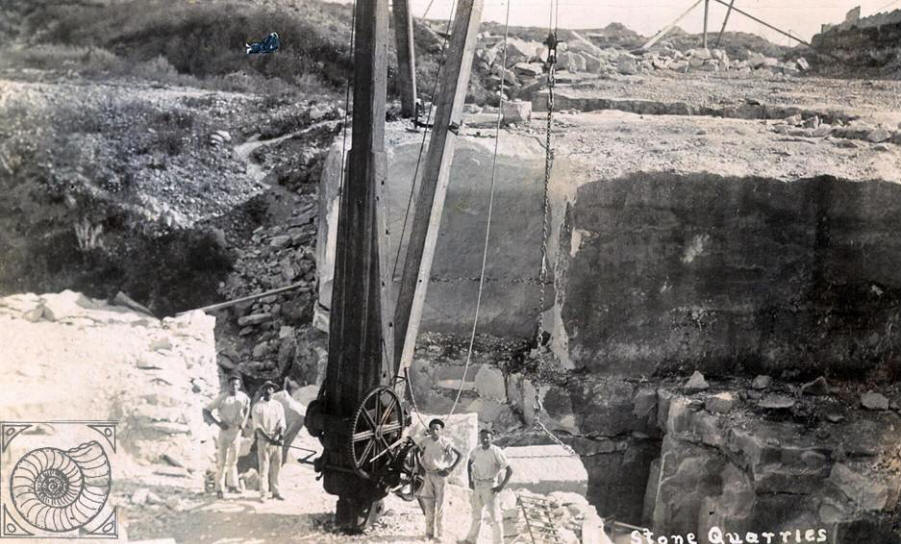

Construction of the path and landing, from approximately the same area as the photo below. Photo courtesy of the Land & Garden Preserve.

Rodney: So, what can I help you with?

Jenn: Tell me about these photos.

Rodney: Sure. We got these from Ken Savage. Ken was Charles [Savage]’s son. … Just to back up a bit. … Joseph Curtis was a Bostonian who set up sort of a rusticator’s colony up Thuya Drive. He had built a procession of houses … up to the last house, which is now Thuya Lodge. He had envisioned a place for residents of Northeast Harbor and their guests, where they could walk. This was sort of simultaneous to the whole concept of what became Acadia National Park. This movement was afoot. … Charles Savage was running the Asticou Inn then, [and he] was approached by Curtis to take over the responsibility of the Asticou Terraces. … There was some money there, and over time he hired crews to build the walkways, which are there now, including this dock, because Curtis had wanted a dock.

The path down to Asticou Landing.

We actually have the language of the deed from Curtis that states this dock and float should be open and accessible for the residents of Northeast Harbor. I think he had envisioned people coming over from Northeast Harbor, across the harbor, docking here, coming up the ramp, and then eventually making their way all the way up, … enjoying the Asticou Terraces.

Jenn: Do people do that?

Rodney: I would say some people do, and I’m not a good judge of monitoring it, but Rick LeDuc who’s Thuya’s manager said he sees people utilize the space and visit the gardens … Curtis did not have the gardens. He had an orchard up there. Savage added the gardens in the late fifties. …Those were Beatrix Farrand’s plants from Reef Point.

Jenn: I didn’t realize that! I knew that they went to the Asticou [Azalea Garden], but

Rodney: If you read his first statement of purpose, which is down in the Rockefeller archives in Tarrytown, New York, his original intent was to move Farrand’s collection to Thuya, because that’s all he had responsibility for. He was trustee of Thuya. So, he had envisioned, ‘we’ll turn Thuya into essentially an Arnold Arboretum for the north,’ because some of the plants at Reef Point had come from Sargent, who was the director of the Arnold Arboretum. [Ed.note: Charles Sprague Sargent https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Sprague_Sargent , professor of botany at Harvard University and the founding director of the Arnold Arboretum, was one of Beatrix Farrand’s early mentors.]

When Farrand sold Reef Point to Robert Patterson, Bob Patterson, [he] wanted to sell the plants, where they were going to just demolish them. Charles Savage wrote a proposal to John D. Rockefeller Jr., and said ‘could I get your financial backing?’ Rockefeller gave him the money to move [the plants], and then when he started moving the plants … he found that Thuya was not large enough. He wrote another proposal to Rockefeller saying, ‘here’s my vision for Asticou [Azalea Garden],’ which was a swamp.

Jenn: Wow.

Rodney: They sculpted the pond and moved the remaining plants from Farrand’s collection to there. Anyway, that’s where Curtis’s [original] vision of having this procession up to the lodge sort of morphed, and Savage added on the garden to it. He’s the one that hired the crews to build the stone stairs, and the lookouts, and so it’s a combination of both men’s vision.

Jenn: Which one built the library up there? Isn’t there a botanical library?

Rodney: Yes. There is. I’m thinking that Savage had a strong hand in the formation of that with the rare volumes and collections. In the Northeast Harbor library, they actually have the trustee’s report, which Savage put together. And it is amazing. The photographs of the gardens being formed.

Jenn: Oh my god, I’ll have to look for that.

Rodney: A lot of these are in that report.

Jenn: Okay.

Rodney: He has ledgers. He has balance sheets. He has everything. Quite exhaustive book. You can go down in the archives and see the original trustee’s report, which outlines that.

Jenn: I’m going to have to do that.

Rodney: Yeah. It has the inventory of the rare book collection – I think portions of it were sold prior to Thuya becoming a part of the Land and Garden Preserve. I mean, there were some rare herbals that were in that collection [and are] no longer there.

Jenn: Okay.

Rodney: Anyway. I could go on.

Jenn: Please do. This is fascinating. … I read [Letitia Baldwin’s book about Thuya] a year or so ago, so I’ve forgotten some of the finer points. …

Path to the Asticou Landing. Photo courtesy of the Land & Garden Preserve.

Rodney: This one here [pointing to the photo above] … I find really cool. …This is the ramp we walked down to get here. This was [and] … is a public way. As I understand it, before Peabody Drive was expanded, and I don’t know when that was done, it was a … gentler slope, and you can see here, Savage had some vision of a mixed garden. And the garden actually continued, and there was a shelter here as well. These power lines are along Peabody Drive. This was a totally different experience down to the dock and along the shore of North East Harbor. Supposedly, … there was a walkway, or there was some form of a walkway all the way to Seal Harbor. I don’t know if it followed the coastline, or if it followed Peabody Drive.

Jenn: It’s interesting. I don’t remember seeing that on any of the old path maps. [Ed.note: I still haven’t been able to find a map that shows it, but I’ve heard about the old path from more people since this interview.]

Rodney: Again, this is all hearsay that this kept going. The kids could ride their bikes from … the Asticou Inn or Northeast Harbor – they could follow the sidewalks and go all the way to Seal Harbor.

Jenn: That must have been so cool.

Rodney: Yes. There’s a small group of us who are trying to get expanded shoulders on Peabody Drive so we can get bicycle and pedestrian [access], safer access all along. Anyway, knowing that Peabody Drive can’t get wider here because of the slope, it might be interesting to see if this ramp could keep going. And that could resurrect the old walkway.

Jenn: That would be great.

Rodney: Yeah. Then you’d go below Peabody Drive if you’re on a bicycle, and then slope back up and connect on the other side.

Jenn: How are the property owners reacting?

Rodney: Those that know about it thus far have been great. Anything to have safer access for their families and for their kids, but we haven’t talked to everybody. That’s the next step.

Jenn: I’ll tell you, talking to everybody takes a lot of time.

Rodney: It does. But it’s so critical to the process, that’s for sure. We’ve had some along Peabody Drive have just said, “yeah, great idea.” We’ve had no one say no yet.

Path to the Asticou Landing. Photo courtesy of the Land & Garden Preserve.

Rodney: This is looking back up [the path]. I think this was gravel. …

Jenn: Yeah. It looks like a carriage road, sort of.

Rodney: I think that’s what it was. I think this surface was gravel as well [the surfacing of the terrace at the dock, which is currently old, cracked asphalt]. We’re talking about, in the future, taking this asphalt up and restoring it back to gravel.

Jenn: That’d be nice.

Rodney: Yeah. Changing the overall appearance. [Pointing to another photo.] I don’t know exactly where this is.

Path near the Asticou Landing. Photo courtesy of the Land & Garden Preserve.

Jenn: Wow. It looks like … the path was closer to the water.

Rodney: Right. This is a really cool photograph.

Jenn: It’s a beautiful view. It’s kind of a neat railing too.

Rodney: It looks like Asticou Terrace’s [railing], but then there’s the water. I’m not sure exactly where this was, unless it was a continuation of the pathway past the copper beech there.

Jenn: Yeah. Have you tried to find that tree?

Rodney: No.

Jenn: Do you know when the photos were taken?

Rodney: [Charles Savage] took over as trustee in the late twenties. … It was in sometime in the thirties, would’ve been my guess.

Photo courtesy of the Land & Garden Preserve.

Jenn: I notice there’s no mechanization in the construction photos. It looks like they’re doing it all by hand here.

Rodney: Right. I don’t know if there was a steam powered winch that pulled the cables so they could lift the stones or not.

Ed.note: the original photos are much darker, I’ve brightened these a lot, so you can now see the base of the crane a little. You know me, I went off on an internet hunt for the type of crane that might have been used. It looks a bit like this pre-WWII British hand-driven crane:

And here’s a fascinating and only slightly relevant page on the history of human-powered cranes.

Rodney: And who these guys were, I don’t know if they were the Candages or who [Savage] had employed to do the masonry work. I’m sure that information is buried somewhere and can be found.

Jenn: That would be cool to find out.

Construction of Asticou Landing. Photo courtesy of the Land & Garden Preserve.

Rodney: Yeah. A lot of the work at Seal Harbor was done by Candages. They actually did a lot of the retaining walls that you see around Seal Harbor, but then who did Northeast Harbor? I don’t know.

Jenn: I’m trying to remember. Was it the Candages who did the Village Green at Seal Harbor?

Rodney: I think so.

Jenn: There used to be a low retaining wall. It’s kind of buried now. Only the top bit of it still shows. [Ed.note: Yes, it was the Candage firm and there are photos of it in Coast Walk 14.]

Rodney: It’s in that book about Seal Harbor-

Jenn: Yeah.

Rodney: … that little folio book.

Jenn: Oh yeah, Remembering Seal Harbor or something [Ed.note: Revisiting Seal Harbor]

Rodney: Yeah. They talk about the Candages, and I think they probably did that wall up by the church. If you’re leaving, if you’re going past the coffee shop on the right, there’s a beautiful stone wall there.

Jenn: Oh right, when the houses … like when you’re heading out of Seal Harbor. Yeah, that is a beauty.

Rodney: That wall keeps going. There’s one right opposite of the store fronts.

Jenn: Oh. Maybe that’s the one I’m thinking of.

Rodney: And then tucked up in the woods is a summer church.

Jenn: I didn’t know that.

Rodney: It’s a stucco church that’s only open in the summer time.

Jenn: Okay.

Rodney: You should check it out. It’s beautiful.

Jenn: I will.

Rodney: Yeah.

Jenn: The other really beautiful stone wall there is the one on that little tiny Farrand garden.

Rodney: Where’s the Farrand garden?

Jenn: When you’re in the intersection, with the little spring in the middle of it-

Rodney: Yeah.

Jenn: … just to the right, it steps down. It’s like a little half circle. It’s a memorial to, I think Edward Dunham. [Again, photos of it in Coast Walk 14.]

Rodney: Right above the playground.

Jenn: But gorgeous stone work there. If you haven’t been in there, stop some time.

Stonework along the Asticou Landing path.

Rodney: I’ll take a look. This walkway here… the pathway’s part of Thuya, but along the way, there’s a fence.

Jenn: I saw that, with the ‘private’ sign.

Rodney: That’s Richard Estes. [Ed.note: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Estes and https://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/estes]

Water Taxi, Mount Desert, 1999. Collection of the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Missouri.

Rodney: He’s a painter. In New York. He has the house across the street from Thuya’s parking lot. There’s that white house on the hill, and then he has the dock. The people just adjacent to the parking lot, I met them this summer, and I think they’re from the Philadelphia area. There’s Story Litchfield, and then there’s a house that’s for sale. I want to say, then it’s the Inn.

Jenn: Yeah. They’ve got three or four of those little cottages, right?

Rodney: [Those] were different Savage homes, and they moved them around. Sam McGee is a great resource. … Sam wrote that article for the Historical Society. …It talks about how the family moved houses.

Jenn: What? I haven’t seen that.

Rodney: [About] the Savage family, that whole area of Asticou, … they would take a home and then add onto it, and so that’s where a whole village of the Savage family was. [Ed.note: “They Should Have Constructed Their Buildings on Wheels,” by Samuel Savage McGee. See bibliography.]

Jenn: Neat.

Rodney: They would have a winter house. Then in the summer, they’d move back off the street and live in the summer house [Ed.note: so they could rent out the big house to the summer people.] Then went back to their big house [in the winter.]

Jenn: Cool. Sounds like people are still doing that.

Rodney: It was a precursor to Air B&B.

Jenn: Yeah. You know, that’s my main income these days.

Rodney: Is it really?

Jenn: Weekly rentals. Yeah. It’s a way to [make a living] on the island, you know?

Rodney: And you’re working with LARK?

Jenn: Yep. Although less of that now. Brian and I bought the house next door to us about a year and a half ago. … It was pretty tumbledown, so we’ve been renovating it and renting it out. That’s been taking all my time.

Rodney: I bet. You doing the renovation yourself?

Jenn: A lot of it. I spent most of yesterday learning how to stop the stairs from creaking.

Rodney: How do you do that?

Jenn: Apparently the creaking is caused when the various [parts] of the stairs get loosened up over time and rub against each other. I tried a couple of things that didn’t work, so I finally took apart one of the stairs. Pried the tread up as much as I could. [Ed.note: So I could see where the stringers were.]

Rodney: Right.

Jenn: Then I got really long, finish-head screws-

Rodney: Okay.

Jenn: … and screwed everything all back together really well.

Rodney: And that worked?

Jenn: Yes. I got rid of like ninety percent of the squeaking.

Jenn: I meant to ask you, how did you end up here? You started what, like two years ago?

Rodney: Two years ago. Interesting question. We were in Boothbay for three years, working at the botanical gardens down there, and prior to that I was at Longwood Gardens for eight years.

Jenn: I didn’t know that.

Rodney: Yeah.

Jenn: Cool.

Rodney: I was down there for eight years. It was a great job, but I was ready to do something different. Somewhere else. We had always vacationed up here. Carrie went to college with Sarah Richardson Stanley [Ed.note: Sarah’s a landscape designer and an old friend of both myself and Carrie Eason. She lives on MDI. Hi, Sarah!] We started vacationing up here in college. Then we went, let’s move [to Maine]. Then the job opened up in Boothbay, and then, I don’t know, two years ago when Carole Plenty was retiring, the reserve hired a head hunter, a search firm. They had gotten my name, and I came up and interviewed and went through the various processes. They offered me the job.

Jenn: That’s awesome.

Rodney: It is awesome.

Jenn: Kind of flattering to be recruited like that.

Rodney: Definitely so. The ironic thing is that I was practicing as a landscape architect the first time we came up here, which was 1997. I had been doing some gardens, but not to the extent [I wanted] – intimate spaces in designs make me feel like, yeah I’m glad I’m in this profession. I remember we walked into the Rockefeller garden, and I had been in North Carolina where I was practicing in Raleigh. Our firm was doing parking lot fit-outs [and] warehouses.

Jenn: Oh god.

Rodney: Essentially, I was doing planting design by code. For x number of parking spaces you have to have x lineal feet of shrubs. And you have to have x number of trees. You draw a radius around each tree, and there can be no open space from the radius anywhere. I said, ‘I can’t do this, this is not what I went to school for’. When I walked in the Rockefeller garden, I said ‘I want to be in the garden, I need to change my career.’ Then, pretty soon thereafter, I left landscape architecture and went into gardens.

Jenn: Wow.

Rodney: Yeah. Now I get to work here, which is really cool.

Jenn: Yeah.

Rodney: It’s funny. Over twenty years ago.

Rodney: Back to this, is there anything I can help with? Are there any questions you have for me …?

Jenn: I think you just gave me some pretty interesting information! What I’m looking for [is hard to explain] … it’s an intersection between the natural history of the place and its cultural history. There’s so much intersection on this island. It’s hard to find a square inch of shore line that hasn’t been used. Colonized. I’m just fascinated with the way … that people have used the island for making a living, and for recreation, and for things that blur the lines between those. I don’t always know what I’m looking for until I trip over it.

Rodney: Right. I get it. You talk about tripping over it … one of the things [I’m interested in is] the Seaside trail, I’m really intrigued by Edward Rand.

Jenn: He did the maps, right?

Rodney: And he was the botanist of the Champlain Society. He did the first floristic inventory of Mount Desert Island.

Jenn: Yes. I’m thinking there was a map that went into the book?

“Map of Mount Desert Island, Maine / Compiled for The Flora of Mt. Desert Island by Edward L. Rand.” 1893.

Rodney: He had the map commissioned with topography so he could mark where he found the different colonies of plants.

Jenn: Yeah.

Rodney: There’s a lady [who] did an internship or some grant with Acadia National Park. She went back and tried to find some of Rand’s colonies.

Jenn: Oh, cool.

Rodney: And … because of the herbarium samples, and because he mapped everything prior to GPS … and he gave physical descriptions of where everything was, she tried to extrapolate where he was. She’s showing thirty percent species loss. [Ed.note: Rodney sent me the info later. “The Changing Flora of Mount Desert Island” by Caitlin McDonough MacKenzie, see bibliography below.]

Jenn: Oh, wow.

Rodney: She says, “is this climate change?” It’d be wonderful if someone had the time, and had grant money to not only take Rand’s information with flora, but also take the other information from the Champlain Society related to climate. And be able to say, this is how much things have changed in a hundred and twenty-some years.

Jenn: Yeah.

Rodney: Anyway … Going on the Seaside trail, there’s a plaque there.

Jenn: Wait, which is the Seaside trail?

Rodney: That’s the one you have to go up the private driveway, across from Seal Harbor Beach, west of Stanley Brook Road. It goes up to the Edwards property.

Jenn: Okay.

Rodney: And then if you veer off into the woods, there is a big boulder with a memorial plaque to Edward Rand. It talks about him conducting that first flora of Mount Desert Island.

Jenn: Wow. I’m going to have to look for that.

Rodney: Yeah. Yeah.

Jenn: I didn’t know that was there. …

Rodney: They had to maintain that, for the Seaside trail, because the Seaside trail went, as I understand it, from the hotel … to the Jordan Highlands. [Ed.note: the old Seaside Inn was in the meadow at the Seal Harbor Beach. See Coast Walk 14 for photos.]

Jenn: Yeah. I didn’t realize it was still there. That’s so cool.

Rodney: The trail’s still there. And Acadia National Park worked this summer to restore it, and so they’re actively working on it there.

…

Rodney: Someone who’s really good about knowing where the old trails are is Keith Johnston. He’s in charge of all the trail maintenance for Acadia National Park.

Jenn: Oh. Wow. Is he still doing that?

Rodney: Yeah, he’s based at McFarland Hill. …

Jenn: I should talk to him.

Rodney: You need to talk to him. Keith’s the one who said … I don’t know how many miles of abandoned trails there are in Acadia National Park. Is there a secret map of abandoned trails?

Jenn: There are a couple of blogs online where people hunt them down and try and tell you how to get to them. But I don’t know of any published maps.

Rodney: Yeah. Me either. I don’t know if Tom Saint Germain’s working on one or not.

Jenn: I don’t know. [Ed.note: I actually just heard about a book of abandoned trails, although I haven’t read it yet: The Acadia You Haven’t Seen, by Matthew Marchon.]

Rodney: I’ve walked the Iron Rung trail, which is Hunter’s Beach. Have you ever been there?

Jenn: No, I haven’t. Where does it start from?

Rodney: It starts at Hunter’s Beach, and it goes towards Dick Wolf’s. There’s the old, iron handrails.

Jenn: Oh! Yeah. I have, actually. It used to be called the Seal Harbor trail or something.

Rodney: It went all the way around.

Jenn: Yeah. There’s still a lot of those handrails up there.

Rodney: Did you do that?

Jenn: Some of it, I did. A lot of it, I was actually down on the tide line. I went with Tim [Garrity] from the historical society. Tim and I went exploring over there from Hunter’s Beach. [Ed.note: That was Coast Walk 13.] Yeah. The funny thing is, the minute you see those handrails … you’re like, village improvement society. Like, nineteen hundred or so.

Rodney: Yeah.

Jenn: There’s just something so characteristic about them.

Rodney: That’s so cool to know that that went around. I’d love to [know] if they have similar things over there in Northeast Harbor.

Jenn: I haven’t done my research over there yet. I’ll let you know if I find anything.

Rodney: Okay.

Jenn: I found remnants of the bridges that used to cross some of the gaps in the trail over there. The bridges are long gone, but you can see where the pipes anchoring them were.

Rodney: Would that have been near the Basses, or where?

Jenn: No. This was more around the point toward Hunter’s Beach. It was probably more like on David Rockefeller’s land there. The part that’s semi-public. There was a lot of the trail still left there.

Rodney: Okay.

Jenn: I got permission [for the Coast Walk] from the next landowner, and … I think there was some on [that] property too. …

Rodney: Nice.

Jenn: Bits and pieces there.

Rodney: Wow. Such an interesting place.

Jenn: Yeah.

Rodney: I love living here.

Jenn: Me too. Finding all the old traces, and decoding them.

Rodney: It’s rich with history.

Jenn: Yeah.

Rodney: The preserve has numerous endowments that help fund the operations of the preserve. Curtis set up an endowment … that was transferred to Savage when he was trustee. … That is to help maintain this. It’s modest, but it helps maintain this area, because he wanted it open and accessible to the public.

Jenn: It’s amazing to me how many people have done things like that on this island. Like, in addition to the Park there are all these little holdings of semi-public access points.

Rodney: Yeah. I haven’t read anything specific, I’m sure it exists, about the mindset or the ethos at that time. This summer, I read the biography on Alexander von Humboldt by Andrea Wulf. Wonderful book. He inspired so many naturalists, including Darwin. When Darwin was doing his research in the mid eighteen hundreds, then of course the intellectuals of Harvard said, “Oh gosh, we can explain things through analysis of our natural ecosystems. We have to go study and explore.“ So the Champlain Society was a manifestation of this Darwinian concept of being able to learn nature through observation … I’d like to think that Curtis wanted to promote that. I don’t know that he explicitly did that, or if it was just to convene with nature. You know, Olmsted had that similar philosophy where nature’s what cures you.

Jenn: The lungs of the city.

Rodney: Yeah. Yeah. … Nature itself is a hospital, and I like to think we live in one gigantic self-healing place.

Jenn: Yeah. It needs a little bit of care.

Rodney: We all do.

Jenn: Do you know what I’ve found interesting, is that in the last year, I’ve started to hear more and more professionals on the island start talking about climate change in public lectures. Mary Roper brought it up, when she talked at the Farrand Society.

Rodney: Yeah.

Jenn: I was just at John Richards’ and Sam Eliot’s talk [about the book they wrote about Little Long Pond.] They were talking about climate change at Little Long Pond … . Are you seeing effects up there [at Thuya]?

Rodney: We were just talking about this. I’ve only been in Maine five years. I love it here … I grew up in North Carolina where you can plant in January, it just never stopped. When I first moved here, people didn’t plant until Memorial Day, and you sort of quit in late September. And I’m thinking, why are we quitting? Then all of a sudden in December everything freezes up and you realize why, but [now] everybody talks about, gosh the season’s really extending here into the fall. We’re seeing the seasons grow longer on the shoulders. I think, of course the red pine scale is the canary in the coal mine.

Jenn: Oh yeah.

Rodney: There will be no red pines left on the island. It’s just a matter of what’s next. When we were down on the Boothbay peninsula, there was [an] outbreak of the Hemlock woolly adelgid which is slowly making it’s way up the Maine coast. Someone told me, as a measuring stick, that the adelgid cannot survive minus-twenty [degrees], like minus-twenty is the killing point.

Jenn: Wow. So, we’re not even getting that [cold] anymore.

Rodney: No. The adelgid, I think is down near the Camden/ Rockland area, and slowly making it’s way up. It’s probably just a matter of time before we see the hemlock woolly adelgid on our native hemlock stands. There are only a few of them on the island, but still.

Jenn: It’s going to be depressing.

Rodney: It is. It is. [Like] the mid Atlantic when we were in Pennsylvania or even in the south, [where] so much of the native understory now is taken over by invasive exotics, because there’s really not a hard freeze that chokes them out. Here … there’s [still] predominately native vegetation.

Jenn: I haven’t been hands-on involved with the plantings for a long time, but [as a landscape architect] I was seriously worried about the birch borer, and the viburnum beetle. I had stopped planting the native birches.

Rodney: It’s tough. That, and you’re right about the viburnum leaf beetle.

Jenn: Yeah.

Rodney: Again, in Boothbay, we didn’t really plant viburnum for that reason. It’s nice to come here and see some viburnum.

Jenn: But the problem with planting them is that they’re so much more vulnerable when they’re recently planted. It’s the same thing with the birches. The existing stands seem to have more resilience. But if you plant a birch … they just kept getting devastated. The yellows and grays seem to be tougher, but the paper birches, which is what we all love and want, I just stopped planting them. Which made me so sad.

Rodney: Unfortunately, to deal with that, you either change species or you start using something like Merit, which is an insecticide, and inject the plant.

Jenn: Yeah. It has to be systemic.

Rodney: At the preserve we don’t use any artificial insecticides or pesticides. … It’s just a matter of species selection. You’re right, either the [plant] palette’s going to get really limited with climate change, or there’s got to be some flexibility, because, I don’t want to get off subject, but people [are against] GMO. I understand that standpoint from a food standpoint, but from a landscape adaptability/survivability standpoint, there’s got to be some research done with native species. And whether that’s finding certain characteristics of native stands and being able to breed that into others so that it can survive a certain climate, like the National Arboretum has been working for years on survivability of hemlocks.

Jenn: And elm.

Rodney: Right.

Jenn: The whole … the Patriot elm and all that.

Rodney: A buddy of mine, who’s the director down there, he’s like, “You want to see a slow process? Get into tree breeding.” Because you can’t release it until like twenty years. You have to breed it, you have to select, and then you have to watch its resistance before you bring it onto the market. He’s like, you could release one or two trees your whole career.

Yeah, those are some of the things that we’re starting to wonder. I would love to talk with someone who’s, say, at the Bio Lab, who’s looking at things under a microscope. What are the invasive biologicals that we can’t see with our eyes, but we can see under a microscope?

Jenn: Oh, that’s a creepy thought.

Rodney: How is that microscopic level changing with climate change?

Jenn: Yeah.

Rodney: The reason I bring that up is, a few years ago I saw at a conference, a lady was talking about diatoms, and she was talking about how there are healthy diatoms in water. She monitors the lakes around Florida and … Florida’s now being overrun with invasive diatoms from bilge water from other countries.

Jenn: Wow.

Rodney: At the microscopic level, the foreign diatoms can actually run out the native diatoms which affects the whole fish life cycle.

Jenn: Yeah. We’re seeing stuff up here with bryozoans and tunicates.

Rodney: Oh.

Jenn: They’re not microscopic, but they’re fairly small creatures. We’re definitely getting some invasions of those. So yeah, it’s at every scale.

Rodney: Yeah. Maybe there’s a summit that needs to occur at some point on MDI about the effects of climate change.

Jenn: Probably wise, because a lot of things are going to happen. Like at the book talk [the other] night, they said just flat out, “When sea level rises, Little Long Pond is going to be a cove.” I was like, wow that’s hard to picture.

Rodney: Yeah. Depending on what happens with the model. It’d be a tidal response, and what kind of engineering effects would go into place to either abate that or allow the ocean to flow more freely without Peabody Drive being washed out.

Jenn: And that would be a trick. You’d need to do a bridge.

Rodney: I know. I know. I mean, the sea wall holds it back to some extent in the winter time, but that’s managed. A friend of mine is the director of the botanical garden in Oklahoma, and a lot of their funding comes from families connected with petroleum. He cannot mention climate change. He is not allowed to acknowledge it or mention it.

Jenn: That must be tough. Do you get any pressure?

Rodney: No.

Jenn: Good.

Rodney: Not at all.

Jenn: Yeah. I don’t understand how something so fundamental and world-changing has become so politically charged.

Rodney: Yeah.

Jenn: I mean, I do understand it, but it seems like even the people who don’t want us to acknowledge it are going to be affected by it. It seems like just self-preservation.

Rodney: I don’t get it. I don’t get it.

Jenn: I’m sorry. Didn’t want to go down that path.

Rodney: No, that’s fine. I think if anything, thinking about these particular gardens, how’s the aesthetic going to be in the next fifteen to twenty years. I mean, the aesthetics of these gardens are predicated on either the asian style or this English-cottage style.

Jenn: Yeah.

Rodney: With longer seasons or warmer springs or variable temperature fluctuation, I think, if anything, we’ll need to have an area for trial and research if we want to maintain that aesthetic. What are some plants of maybe different cultivars or different species that would be able to maintain that aesthetic, or do we slowly shift the aesthetic to use plants which are more adaptable to this climate? Or the changing climate.

Jenn: I think you’ll be able to keep the aesthetic in most cases.

Rodney: Yeah.

Jenn: Using warmer climate plants.

Rodney: Sorry. It’s my kid texting me.

Jenn: Have we taken too long? I know you’ve got a pretty full schedule.

Rodney: It is four.

Jenn: It is? Oh my gosh!

Rodney: I’ve got to go. [We walked up to the start of the path.] Just ignore this bittersweet. One of our projects [as] part of the renewal of this [dock area] is to rethink the landscape, which is this amalgamation of natives and of exotics. It’s interesting that Farrand had dwarf spruce at Reef Point, and at some point Savage or one of his designees repeated that as these sentries. Over time they’re no longer dwarf spruces.

Jenn: They’re a little out of scale now.

Rodney: All right. See you later.

Jenn: Thank you again.

Rodney: My pleasure.

WORKS CITED

Baldwin, Letitia S. Thuya Garden: Asticou Terraces & Thuya Lodge. Mount Desert Land & Garden Preserve, 2008.

MacKenzie, Caitlin McDonough, “The Changing Flora of Mount Desert Island.” Chebacco, volume XVI, 2015.

Marchon, Matthew. The Acadia You Haven’t Seen. CreateSpace, 2017.

McGee, Samuel Savage. “They Should Have Constructed Their Buildings on Wheels,” Mount Desert Island: Shaped by Nature. Maine Memory Network, April 2013. Date accessed: October 9, 2017. http://mdi.mainememory.net/page/3806/display.html

Vandenburgh, Lydia and Shettleworth, Earle G., Jr. Revisiting Seal Harbor and Acadia National Park. Arcadia Publishing, 1997.

Wulf, Andrea. The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World. Random House, 2015.

ADDENDUM

Another photo of the path from Asticou Dock to Seal Harbor, looking back at Asticou Dock.

Hi Jenn,

I’ve bushwacked around this area quite a bit trying to follow the old paths. The lower path is the easier one to follow and it’s not really easy. There is a dry stone wall along a good stretch of the beach with several collapsed parts. Trees have grown in making following it tough but it can be more or less followed to the first driveway to the south.

The upper trail is thickly grown in and difficult to follow. It goes from the first turn on the terraces trail, parallel to the road, almost to the Asticou Drive.

Lots of good info here. I haven’t met Rodney yet.

See you!

-Kenn-

So cool, Kenn! One of these days I’m going to have a party so all the Coast Walk people can meet each other.

Pingback: Asticou Dock, January 29, 2019 (Beachcombing series No.92 – Jennifer Steen Booher

Pingback: Coast Walk 18: Roberts Point, Northeast Harbor – The Coast Walk Project

The coastal walk 18 was published a few years prior to gazing upon it last night…

Is this reply section active?

yes, it is.