May 6, 2015: 6-11:30am, forgot to note temperature, probably in the low 60s when we started, might have been 70ºF by the end of the walk. 1 Red Squirrel, 2 Herring Gulls, 1 Purple Sandpiper, flock of 10 Guillemots, 1 Cormorant being harassed by a Herring Gull, 5 birds flew by overhead that might have been Canada Geese.

Walkers:

Kelley Sanborn, Director of Special Services, Mount Desert Island Regional School System

Lilea Simis, owner, Town Hill Market

Kelley and I met at the Great Head parking lot at 6am on a bright, sunny morning. (Lilea had to get her kids off to school and planned to join us later.) It was about 45 minutes after sunrise, and the day still felt all new and shiny. We struck out along the path, talking about the long winter and how beautiful the day had turned out. Certain people may have started singing, “Oh what a beautiful morning” because we’ve known each other for twenty years and it no longer matters if certain people can carry a tune or not.

Even though we’ve moved into new geologic territory, hiking over Cadillac Mountain granite now, the shoreline continued the pattern I’d seen all along of headlands and coves. Along this mile or so between Sand Beach and Otter Cliffs, the headlands tended to be weathered and rounded, while the coves were filled with enormous round cobbles.

Kelley has had some trouble with her knee, which has to be intensely frustrating for such an active woman (her snowshoes got me through the winter!), so when I went scrambling down the rocks to check out tide pools, she mostly followed along the trail at the top of the cliff. (That’s why she’s so far away in the photo up top.)

from “A Souvenir of Bar Harbor – Mount Desert Maine,” W.H. Sherman, 1893. Photo courtesy of the Jesup Memorial Library

There were a few spots where it was possible to get down to sea level, but the stones were covered with a slippery algae I don’t remember seeing before. It was dark green, and Kelley called it “Elvis velvet,” because it looked like the background of one of those paintings of Elvis on black velvet:

I haven’t identified it yet. It was lovely, but inconvenient. You can see it glowing bright green in some of the photos:

I did eventually find a safe spot to climb down. In one of the pools near the top of the descent (not a tide pool, too high up, probably runoff) I found a dozen or so things that looked like caterpillars. I assume they are some kind of terrestrial larvae that were washed into the pool by the last rain storm. At least one was still alive, I couldn’t tell about the others.

Looking over the edge of a cliff, Kelley spotted this cutie, which I think is a Purple Sandpiper, hunting for breakfast.

The discovery of the day was a long, narrow tide pool full of tiny anemones.

They were about the size of a quarter, and almost translucent.

Ever since Schooner Head I’ve been finding wildly striped Dog Whelks. I had no idea their shells could be so varied.

The lowest tide pools had forests of seaweeds:

Then there was this amazing cobble beach. I’m not sure you can actually call it a cobble beach, it was more of a boulder beach. Those stones are all big enough for both my feet to stand on, and the cliff face must have been forty feet high.

Of course I had to go exploring in this forest of sea stacks!

The size of the boulders made it difficult to walk – your foot only connects with a small part of the curve, so every step is wobbly.

By the time I crossed the cove it was 8:30am, and suddenly we were at Thunder Hole.

The observation platform and walkways at Thunder Hole are being rebuilt, and the Park Service really really really doesn’t want you walking around down there.

Lilea found us just before Thunder Hole, so we all sat on a broad rock ledge in the spring sunshine, eating apples and granola bars, catching our breath. While the three of us are taking that break, I’m going to tell you about a part of the walk that happened a few days earlier, but belongs here at Thunder Hole.

May 3, 2015: 64ºF at 4:30, but by 5:30 had dropped to 52ºF, and the wind got much stronger.

George Neptune, Museum Educator, Abbe Museum, Bar Harbor, Maine, and member of the Passamaquoddy tribe.

You may remember George from the very first Coast Walk on New Years Day. We had planned long ago to meet here at Thunder Hole for the story of Koluscap and the Whale, and he did tell me that story, but we went on to have a long, fascinating talk, touching on Passamaquoddy spiritual beliefs, the struggle to get Maine schools to stop using “Indians” as mascots, and his dreams for the future. He even brought out his drum and sang the most beautiful song.

And my iPhone recording vanished. It was working, I checked it as we talked to make sure, but somewhere between pressing the stop button at the end of our talk, and opening the program to view the video, it vanished. And I cannot get it back. So I’ve tried to recreate as much of the conversation as I can, although it’s all in my own words now, not George’s, and I know I’ve forgotten so many important details, I could just cry.

So.

The story of Koluscap and the whale is part of a much longer story about the epic fight between Pukcinsqehs, a witch, and Koluscap, a kind of demi-god and cultural hero of the Wabanaki tribes. We’ll hear the full story when we reach Somes Sound, where some of it takes place. It is an important episode as it describes the first treaty ever made in the Dawnland, and establishes the importance of the pipe as a symbol of friendship. (Slight digression here, apparently smoking a pipe together is comparable to the European concept of breaking bread together.)

At this point in the story, Pukcinsqehs (sounds like pook-sin-squash) has kidnapped Koluscap’s relatives, Grandmother Woodchuck and his younger brother Pine Marten. He chased her a long distance, but she stole his canoe and set out across the sea with her captives. Koluscap couldn’t follow so he sang the whales’ song and Putep (sounds like “boo-dep”) came to him. He asked her to carry him across the water, but she was worried about running aground and asked him to promise that she would be safe. Koluscap promised, and asked her to promise to keep him safe on the journey, which she did. So he climbed on her back and they set out after Pukcinsqehs.

As they got closer to the other shore, the clams on the bottom began to sing to Whale that she was getting too close and would run aground. Koluscap did not understand the clams’ song, and Whale told him what they were saying and asked if it were true. Koluscap lied and said they were still a long way from shore, so Whale continued swimming. Soon the clams sang to Whale again, warning her that she was too close and would be beached very soon. Again she asked Koluscap and again he told her to keep swimming. Soon poor Whale did run aground, and Koluscap jumped off her back onto the beach. Whale was very upset that he had lied to her, and reproached him for breaking the agreement. Koluscap said, “I promised you would be safe,” and placing the butt end of his spear against her forehead, he pushed her off the beach and into deep water. Then Koluscap gave Whale his pipe to celebrate their treaty and their friendship, and she swam off, with the pipe smoke rising above her.

George chose to tell this story at Thunder Hole because the Passamaquoddy name for this spot is based on the words for ‘blowing water into the air,’ which are also the basis for the whale’s name, Putep. He also pointed out a naturally-formed face in the rock, which fits in with the very end of Koluscap’s saga, in which he left to go to a place behind the sun, where he is making weapons for a battle at the end of the world, but before he left, he set images of himself in the rocks throughout the Dawnland.

Somehow we moved from the face in the rock to the idea of the cleft in the rock as an opening to the underworld. I had to stop George and ask what the underworld is. I don’t like to assume I understand a concept just because I know what the word means. My idea of “underworld” is basically Greco-Roman, but for George, the underworld is not hell, or death, or anything particularly negative. See the seven sides on his drum? One for each direction: east, west, north, south, above, middle (here on earth) and below. Above and below are both spiritual (and this is where I really miss my recording of our conversation!), with above being more ethereal and below more closely tied to earthly things. Things that happen in both places get played out here in the middle, on earth. More to the point, a place like Thunder Hole, a deep cleft in the earth at the edge of the ocean, is a possible point of communication between the realms. As George described it, joining the elements is powerful, and a ceremony here would most likely involve fire, to include all of them. We also discussed his concept of time, which is not linear, but more like a spiral, with distant ancestors still considered family, and part of the current “we.” I’m reluctant to try to paraphrase all this, as I’m in danger of getting it badly wrong. I was raised in the Jewish tradition when I was little, and the Protestant tradition when I was older, and I think in the end religion comes down to stories and belief. Stories are very powerful, and it’s important to get them right.

We talked about the situation in Skowhegan, where George was planning to go the next day for a school board hearing about changing the school mascot, currently the Skowhegan Indians. Skowhegan is apparently the last town in Maine to use that name for their sports team. I admitted my ignorance, and said that for me, personally, if a group of people found the use of their name or image offensive, that would be enough for me to stop using it, but I didn’t quite understand why it was offensive in this case. I grew up in Massachusetts, and there were teams named for the Minutemen, or the Patriots, who used the image of a person as their logo. How was this different, I asked? George pointed out that those were specific groups, well identified in historic or military terms, while “Indians” lumps together entire nations of people who have widely differing customs and histories and beliefs into one dismissive and off-handed term.

Yeah, I can get that.

[As of May 10, the school committee had voted to keep the name.]

In my favorite part of our conversation, George told me about his dreams for the future. He’d like to have a gallery with working studios filled with Wabanaki artists and artisans. Bar Harbor would become an art destination like Santa Fe, where authentic work is appreciated and native symbols are woven into murals and decoration throughout the town (but not misused.) He mentioned the Wabanaki double curve as an example, and once again I had to stop him and admit ignorance: “What’s a double curve?” In answer, George showed me the tattoo on his neck:

By this time the wind had picked up and the temperature had dropped almost ten degrees. My fingers were turning numb, so we headed back to our cars.

By this time the wind had picked up and the temperature had dropped almost ten degrees. My fingers were turning numb, so we headed back to our cars.

It rarely fails – in the course of every single coast walk I learn something that boggles my mind. I generally think I’m pretty smart and well-educated and widely read. I know the whole point of this walk is to learn stuff and become a better artist, but four months in and the biggest lesson I’m learning is the depth of my own ignorance. There is a gaseous form of granite, mice dig tunnels in deep snow, we live on a prehistoric volcano, deer get hurt and I can’t help them, the colonization of the Americas is still happening and I’m part of it, I can climb a steep rock face with my bare hands, and some sea anemones reproduce by splitting in half. What kind of art can I possibly make that would adequately communicate the intricate life of a barnacle let alone the pain the Passamaquoddy feel at having the name of a nation without the actual rights of self governance? I have to hold myself open and accept all the data, even the painful and uncomfortable stuff that I don’t know how to address, in the belief that somehow, when it all gets shaken up together, something big, and powerful, and beautiful will come back out.

…

Back to the sunny day with friends. (And if that gives you mental whiplash, yes, me too.)

I tottered across one more cobble beach, but decided that three hours of scrambling was all my legs could handle, so I climbed back up to the path and we strolled out to Otter Cliffs.

So why is it called “Otter Cliffs?” I’ve come across two stories. One is that they were named for the Sea Mink (Neovison macrodon), which was hunted to extinction by 1870, before it was even cataloged by naturalists. The species was described through skeletons, a taxidermied specimen, and anecdotal evidence. The mink was a coastal dweller, ranged from Casco Bay north to Newfoundland, and was the largest of all the minks. It apparently lived on seabirds, seabird eggs, marine invertebrates, and insects.

The other possibility is that Otter Creek was named for river otters found there, that the town of Otter Creek was named for the stream, and that Otter Cove and Otter Point were named by extension. I’ve found several references that call Otter Point the Otter-Creek Point (see below). In that case, the animal in question is probably Lontra canadensis, the North American River Otter:

River otters can be found in both freshwater and coastal marine areas. They are found throughout the entire US, except where pollution or habitat loss have driven them away. River otters apparently eat fish, turtles, crayfish, and frogs. I’ve never seen one, but the Acadia National Park website lists them as a common species here. Maybe someday!

“After [passing through the Gorge], the road turns up along the Peak of Otter; runs high along the ridgy east wall of Otter Cove, with charming views of the cove and its settlement of farms; and finally stops at a little house. A fee is paid at the farmhouse at the end of the road; and leaving the carriage, the holiday rambler walks along a pleasant path, through a short stretch of evergreen woodland, and emerges on the vast cliffs, at whose foot, [nearly] a hundred feet below, the sea roars and whitens ceaselessly. The trend of the shoreline is visible as far as the yellow Newport Sand [Sand Beach] and the high promontory of Great Head. Otter-Creek Point is over a mile long, between the sea and Otter Cove, and rises to a height of 188 feet, covered with woods, and fronted on either side by noble cliffs. … A mile inland rises the Peak of Otter, a wild foot-hill of Newport [Champlain] Mountain. This region received its name from the otters that once abounded here, but have long since passed away. … Beyond Otter’s Nest, the summer-residence of Lieut. Aulick Palmer, of Washington, a road runs on to the end of Otter-Creek Point. Unless it is nominated in the bond, the buckboard drivers oftentimes decline to drive out over this noble road. On the western side of the point is a notable cavern, near which the natives have dug a deep pit, in the search for Capt. Kidd’s buried treasures. …Otter Cove makes in for half a mile, between high wooded shores; and has on one side a quarry of … red granite. In ancient times the head of the cove was occupied with beaver-dams.” [“The Journey to Otter Point,” M.F. Sweetser, 1888, reprinted in Discovering Old Bar Harbor and Acadia National Park, Ruth Ann Hill, 1993.]

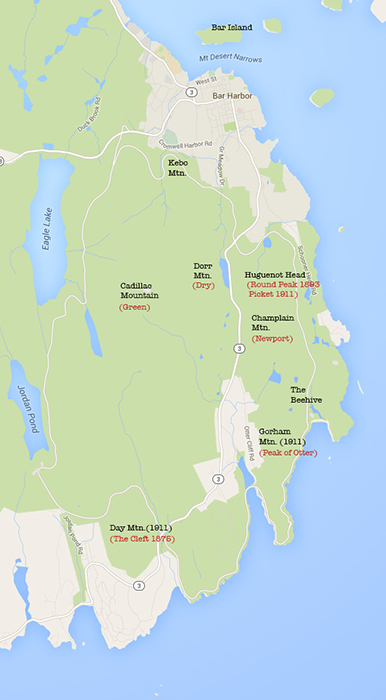

Notice that in the 1887 map, “Peak of Otter” refers to what we now call Gorham Mountain, while on the 1911 map it is the lump of land on Otter Point. Maps from 1890 and 1893 agree with the 1887 map, but there are two 1911 maps that move “Peak of Otter” to the point and call the larger mountain “Gorham.” Mountains moving: I don’t really know what to make of that.

Looking back from Otter Cliffs into what I now know is called Newport Cove, named for the mountain behind the Beehive at left, which is now Champlain, but was once Newport. Newport Mountain and Cove were named for Christopher Newport, an English sea captain who was commander of the expedition that settled Jamestown (in the course of which he almost executed Captain John Smith, which would have been a tragedy for Disney) and who inadvertently colonized Bermuda. The Beehive and Kebo seem to be the only mountains in this area that were not renamed in the last century: they show up with their contemporary names on an 1875 map, the oldest one I have that labels the mountains.

The current names are in black. The old names are in red. After I made the map, I realized that ‘Dry Mountain’ was first changed to ‘Flying Squadron,’ although it doesn’t show up with that name on any of my maps, and was changed to ‘Dorr’ after Dorr’s death in 1944.

I got curious and looked into the name changes very briefly. It looks like most of them were changed in 1918 when George Dorr, in his role as Monument Custodian for the Hancock County Trustees of Public Reservations, made a formal proposal to the National Park Service. Others changes were proposed in 1919 when the Sieur de Monts National Monument became Lafayette National Park, although they didn’t gain approval until 1929. Dorr’s reasoning seems to have been that the old names were boring, and he wanted names with historical associations, which seems a bit high-handed to me. There’s a good, short, article in the Woodlawn Museum’s newsletter that summarizes some of the controversies around the name changes. My favorite quote: “Privately, Ellsworth District Court Judge John A. Peters advanced the popular misconception that if Green Mountain could be renamed Cadillac then logically Dorr “ought to call another one ‘Buick’ and certainly a peak near Seal Harbor ought to be called ‘Ford.’”

My brain feels utterly stuffed at the moment, but when it clears I’ll do some more research and give you a ‘bonus post’ on the mountain names.

More next week as we head around Otter Point into Otter Cove and up to Otter Creek.

I’m loving this trip and your reports. I love the details and hearing about plants and animals,that I’ve never seen before. Mostly, i love that you want to learn about it as much as you can, but that you are also realizing,that names of places and tribes, can’t seem to be hammered down to absolutes. That life and times and stories and recollections change and get altered from one door to the next. It’s great to stuff as much in our heads as we can and as you said…when we shake it all out, the only thing that is an absolute, is that the centuries of people before you AND you, will see the SAME WONDERFUL THINGS!!!! How amazing that we can share that ONE certain thing with our ancestors! Report On! Laura 🙂

Thank you, Laura! I’m so glad you’re enjoying the journey.

Pingback: Interview: Darron Collins at the College of the Atlantic – The Coast Walk Project