May 21, 2015: 7am, 52 degrees at start, bright and sunny. 2 Surf Scoters (Melanitta perspicillata) one male, one female; huge flock of about 81 birds, too distant for positive ID, but possibly more Surf Scoters; 2 female Common Mergansers (Mergus merganser); a lone bird that could be either a Black Duck or a female Mallard (I can’t tell them apart!) Bluets along road, blueberries in flower, spruce buds.

Many of the historic photos and much of the information in this post were taken from two sources: Charles Smythe’s Traditional Uses of Fish Houses in Otter Cove, 2008; and Douglas Deur’s The Waterfront of Otter Creek: A Community History, 2012. Both can be downloaded at those links.

Walkers: Karen Zimmerman and Dennis Smith

Karen and Dennis live in Otter Creek, and are passionate about the history and wildlife of the area. Karen is a graphic designer: we met years ago when she designed the logo for my (former) landscape architecture firm, and she writes a wonderful blog called ‘Maine Morsels.’ I knew Dennis from his work monitoring alewife runs with the Somes-Meynell Wildlife Sanctuary.

We met on the Otter Cove Causeway early one sunny morning in late May:

Jenn: You know what was really funny is [when I was hunting for images of Otter Creek] I went to the Acadia archives and I looked through the finding aid at the Mount Desert historical society and I looked at Bar Harbor, and everyone [said], ‘You should go talk to Karen.’ Apparently you are the resource!

Karen: I collect what I can, but yeah, I mean I love it, I’ve moved to Otter Creek, I’m a transplant, but … it’s a big piece of my life. I love our little village and want to keep its history alive as much as possible.

Dennis: You see this line of rocks? That’s the Otter Creek ledge. It had to be something that they [built] …, when they were doing the granite up here, because as you are probably aware there was a big quarry up here. It stretches from there and goes to the other point over there.

J: Yeah, I actually noticed when I was walking by how shallow it is right off that little point there.

D: I wish I knew the history of it.

J: Must make it really hard to get a boat in and out.

K: Yep, which is why a lot of fishermen left here. One of many reasons that they left here is the difficulty of the harbor. But we’re planning on getting a boat and starting again.

J: Awesome! Fishing, a lobster boat?

D: Five traps. Five trap license. If she has five traps and I have five traps, we’ll get all the lobsters you want.

K: Yeah, not doing it commercially, but just part of our growing our own food, that whole thing.

K: Did you get up to the lookout tower from World War I?

J: No. But I saw your blog post on it. It’s right near the parking lot there, near Fabbri? [Ed. note: the Fabbri picnic area.]

K: Well, part of it’s near Fabbri, but the tower itself is by the other parking lot, the one where the high road/low road goes? It’s just like a skip from there. But that whole point is filled with artifacts and traces of the old buildings.

J: I’ve had to kind of stick closer to the shore, ’cause there’s just so much!

…

K: [There’s a] little fish house on the inner cove

J: Oh cool, there’s another one?

K: Yes. It’s in the book, there’s a picture of it. … [Ed.note: see below]

J: I wasn’t clear that there were 2.

K: Yeah, there’s that one, they actually expanded, it used to be just a blind, like a hunting blind, now it’s really adorable, I’ve slept in it a few times. It’s like a ship inside, with built ins and a woodstove. And … windows that look out over the water. I was there one night and I was … awakened by this sound that I had never heard before, dawn or whatever it was, 5am, and it was 12, 14 blue heron out there and they were screaming at the top of their lungs. You always see them being nice and peaceful – I mean they weren’t being war-like but I have no idea what it was all about.

J: I’ve never seen that many blue herons!

K: Yeah, it was one of those once-in-a-lifetime things.

J: Then suddenly you’re not quite so upset about having been woken up.

K: Exactly!

K: So, how do we do this?

J: We just start walking and talking!

…

D: Did I tell you about my first encounter right here on this causeway that I can remember?

J: No?

D: I was five years old and my babysitter brought me down here – we had a path come right from the house. Down here, fishing pollock. Her name was Wilma Walls, and I every time I saw her since then I was back here getting ready to fish.

J: And were your parents into fishing?

D: Not really. My father hired a boat one time and we went to the harbor flounder fishing. We did not get any. I think that was Harry Park Richardson, he had a boat here, a skiff, something like that. My father hired him, I don’t know what he paid him, he may have just traded him something … I caught a lot of pollock, I remember that, and I’ve been in love with fishing ever since.

K: Driving force in his life.

J: So how did you get into fishing; did you work on other peoples’ boats or get your own?

D: Well when I say fishing I’m not lobster fishing, not commercial fishing. Sport fishing more. Salmon, trout, that type of thing. I did go lobstering once or twice but Mount Desert Rock in February was not my cup of tea.

J: Yeah, that’s a hard life.

D: You’re familiar with the new trail here, right?

J: No, I’m not. You know, I’m embarrassed to say how little I knew about Otter Creek before I hit the Point and started researching. I mean you can’t – it’s invisible!

D: It is

K: And we like it that way!

D: This trail here is an extension of the road where they used to haul granite up beyond my house down here to the ships.

D: The road which they built this trail on was a great road. Still got culverts that they put in over a hundred years ago. They hauled the granite all the way from the Seal Harbor side of my house down here to the ships.

K: It’s the Roman road of Otter Creek, it’s just this phenomenal road that has an embankment almost 8 feet tall of well built granite… And it’s still sound and you can see the tunnels under the road that have not filled in at all in a hundred years. They build new ones and they’re falling apart in fifteen years.

J: I know, I was just thinking the DOT needs to come take lessons!

K: So the Park decided to put a path in and met with the Aid Society of Otter Creek, which I’m glad they did because we had a lot of issues about it being destroyed, and they were just thinking, ‘Oh good, we’ve already got a kind of foundation for a footpath.’ So we teamed together … it was going to be “the Blackwoods Connector” and now it’s called the “Quarry Trail” and instead of hiding the Quarry Road it’s interpreted.

[You can read a little more about the Quarry Trail here.]

D: Are you interested in the history of the fish houses and whatnot here too?

J: Yes!

D: You’ve seen the pictures, there were quite a colony of them over that way, and all within my lifetime. I used to be scared to go in one because there were so many damn spiders. … I suppose they ate the flies that came in for the fish. …We used to be able to go all the way down from my father’s house down to shore here as I said before.

J: And did you guys build this house?

D: Stephen, my brother did.

J: And when was that?

D: [Sighs] Gracious god, fifteen, twenty years ago?

J: There was nothing there?

K: There were the foundations of the prior one, there was always a fish house there.

D: Yeah, the old house.

K: They reconstructed it. So historically there was something there, and there were bits and pieces of it, and there was the old wharf, which I guess got chainsawed out about six years ago, unfortunately.

J: Wait, what wharf?

K: There was an old wharf.

J: Oh cool. [Was it] granite or wood?

K: They were wooden posts and they stuck up this far, and you’ll have to talk to Steve Smith about that because it was one of those clean up days and somebody got ambitious and just chainsawed all these posts off, a hundred and fifty years old. Oops. …

J: I got the sense that the Park’s attitude toward cultural landscapes is changing?

K: Thank god.

D: Well, it is but

K: Too late for many things, unfortunately.

D: I’ll deviate a little bit, you see the alder right here, the catkins, I’m pointing out the male catkins, there’s the male catkins, and out on the end of the far limb there’s the female catkins, see those little …

J: The little berry things

D: The little fat, brown ones. [Laughs]

K: The males are long and dangly, the women are round and fat,

J: I’m not going there!

K: if you want some mnemonic device to help you remember which is which!

Dennis had to leave at this point, and Karen and I started climbing down to the shore.

J: So when did you come to Otter Creek?

K: Oh goodness, fifteen, eighteen years ago, somewhere around there. From Bar Harbor.

J: And did you grow up in Bar Harbor?

K: No, in Connecticut.

J: How did you end up here?

K: I was married to a COA student. COA brings many of us here. And I found my place. We moved up here for a couple of years while he went to school, we got divorced, then he graduated and left, and I’ve been here ever since. And then I moved to Otter Creek because I wanted to get out of downtown, fun though that was for many years. I wanted more space and less noise, and I found the house in Otter Creek, major fixer-upper, and did that. And that’s where I met Dennis.

J: While fixing up? How did you guys meet?

K: I was going for a bike ride and this adorable twelve-year-old came running out saying, ‘Stop, stop, come look!’ And he dragged me over to show a big snapping turtle that was laying eggs.

J: Oh my gosh!

K: And it was Dennis’ grandson, and Dennis was there looking at it and saying, ‘Have you ever seen that?’ and I went, ‘Well, no,’ and we chatted and that was my first introduction to him, and then I forgot all about him. … Then I was on the Warrant Committee and … in between that period he got divorced … and there was the Warrant meeting, and he was in there and I knew someone he was standing next to, so I was waving at my friend and he thought I was waving at him. So he came right over and chatted me up, and we went for a hike, and there you go!

J: So you met over a snapping turtle.

K: And our first date was climbing…

J: Oh that’s fantastic!

K: and poking at scat.

J: Clearly the right sort of person.

K: I have never walked this, down below.

J: Really!

K: Yeah, we drive down there, typically, and sit on those rocks and have tea. And … go to the fish house with all his grandkids … We try to get them down there so we can tell them history and share stuff. A lot of them don’t live nearby anymore so it’s … ‘Let’s go down and have some lobsters at the fish house and we’ll tell you about grandpa and great-grandpa and great-great-grandpa. And Dennis is about to be a great-grandfather.

J: Congratulations! That means that you’re a great-grandmother, though.

K: [laughing] Exactly!

…

J: I’d like to know what you find most interesting about living here or about the history.

K: I grew up in a similar small village in Connecticut … and history was a big part of our lives growing up. So when I moved to Bar Harbor that kind of fell away, and when I came to Otter Creek it just was like coming home. A different place, but it had the same heart, the same sense of small community, almost a sense of not ‘us against the world’ but ‘us together,’ whatever it is.

By now we had wandered almost to the fish house:

K: This is where high tide comes in … we have bonfires right here, cooking lobsters … . This is owned by the Aid Society of Otter Creek, so everyone who lives in Otter Creek and joins the Aid Society is technically a part-owner of this, which I think is nice.

J: Yeah, it’s like the village hall. In a small way.

K: It is. The things that are deeded are the Hall and this. Those are the two pieces of property that are owned by the Aid Society.

J: This is cool [looking at rock in deck] So was the original fish house built around the rock?

K: No. [Pointing to the concrete weights on the rock.] These were all local fishermen, they would put them in their traps for weight. … You can always tell if somebody’s been here since you were here last.

J: I can tell it’s been windy [looking at candle.]

K: I love that it’s communal.

J: Do you ever come down and find people are already here?

K: No. [Pointing down toward shore.] Somewhere down there, I don’t know if Cynthia talked to you about them, are rocks that have black stripes of tar, because the ropes would get coated in tar to preserve them

J: Oh cool!

K: And they laid them on the rocks to dry, and then even sixty years later there are many, many rocks out there that …, you pick up this rock and go ‘what’s this black thing, it’s not an algae,’ but it’s the remnants of the tar. Would you like to see inside the shack?

J: Yes, please!

K: There’s a treacherous path up there [to the fish house from the Park Loop Road]. … The one down [side] is that the Park-Aid Society relationship goes back and forth: … we used to have access historically, for a very long time, and we’d exit through Blackwoods campground. You’d come in here, do your fishing, put your traps on, go out, because it used to be, before it was the Park, a community road back to Otter Creek. But there was a party here, I’m not sure what; raucousness, … people drinking, being stupid, and now they gate that road off. So fishermen have to go from here, or visitors or family or whatever, all the way to Seal Harbor. Out by Jordan Pond and back to Otter Creek. You know, legally they can do it, but they’re just making a point, and it’s just kind of irritating. … So here we have … buoys, I think he’s fishing this year.

J: Is that Stephen?

K: Yeah, and we will be.

J: So then there’ll be three people fishing out of here.

K: And there’s a little … place that you can sleep upstairs. It used to have a dormer, which was wonderful, so you could lie up there and look right out here. I’ve tried to talk him into putting the dormer back in.

J: What happened to it?

K: The roof fell in, … when it was repaired it was easier for them to just pull it off and roof flat.

J: I love everyone’s names written around [on the walls.]

K: Have you ever been in the back of theater at the Grand?

J: No. Names?

K: Names.

J: Seriously?

K: Phenomenal. Wall to wall, upstairs, downstairs, every inch with people. They’re beautiful, they’re really really beautiful. Some of them are graphically drawn and some are scribbled, some are people who I guess have become famous who visited, it’s just a whole story.

K: Last year we had veggies growing back there so when we had a lobster feed we could pick cucumbers. And that’s Steve’s traps.

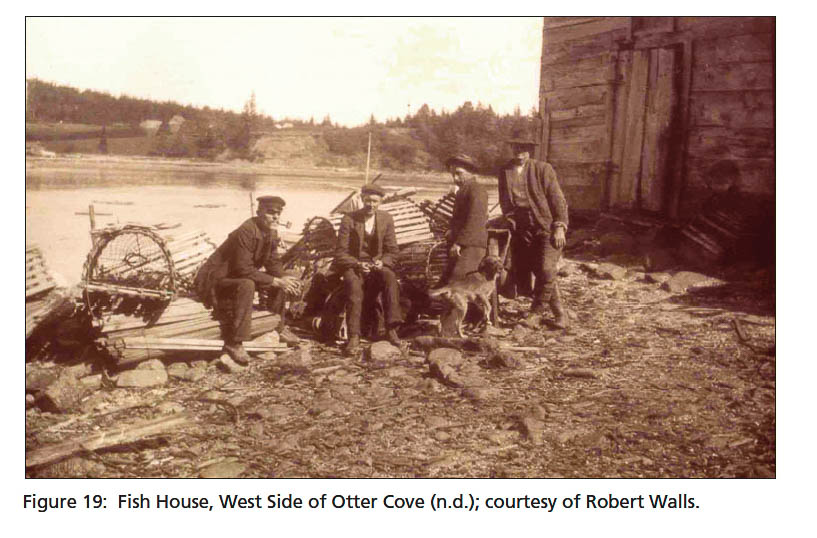

I’m going to interrupt our narrative here to talk about the fish houses. Most of the historical information comes from the studies by Smythe and Deur cited at the very top of this post. On the off chance that you haven’t run into them before, fish houses are found all over Maine (probably all over the world), although they aren’t as common as they used to be. They’re usually shacks or sheds that individual fishermen use for land-based stuff like storing bait and gear and tools, building and mending traps, or prepping trawl lines. According to Smythe’s study, “They were often formerly associated with flakes (drying platforms) used for curing salted cod. They also provided a social space for fishermen as they worked preparing gear and bait for the next day’s fishing.” Here in Otter Creek, they were built without foundations directly on the rocks just above the high tide line. “Interviewees for the current project recalled that, for a time in the early 20th century, the economic importance of these small structures was so universally appreciated that the Town of Bar Harbor actually dispatched staff periodically to maintain the shoreline in front of the fish houses, removing rocks tossed there by waves and performing other minor maintenance.” [Deur]

“Norman Walls describes the use of the fish shacks in Otter Cove during his lifetime: ‘Most of them were shacks, basically, made to hold [bait]. See, you could get your bait in the summertime but they had no place to keep it in the wintertime so they used to get it and store it in the big barrels in there, salt it down. … They were just something that they stored their gear in and their bait in to go lobster fishing. And they used to have to keep it, you know, buy it in the fall of the year to keep it all winter because most of those guys did fish in winters.'” [Smythe]

“My father had two [barrels], and the secret amongst the fishermen was you had to have bait that really was rank. They would make “the Italian fish sauce”—you could smell that stuff for four or five hundred feet. When the shedders started coming in they were all fragile down there and they hide under the rocks because they’re soft as a jellyfish after they shed. So in order to entice them to come out, the fishermen figured you had to have something pretty potent. So they’d make up this bait of herring. I guess some used menhaden or porgies. . . let that ferment real good, you know, and then you’d bait the traps with that.” [Carroll Haskell of Deer Isle, quoted in Smythe.]

Smythe’s report includes some interesting statistics on the fishing population of Otter Creek: “”In the 1870s, there were about 30 fishermen in Otter Creek, and there was a small satellite community with more fishermen on the Bar Harbor side, in the immediate vicinity of the fish houses, which had its own school by 1881. ” There were 27 fishermen on the Mount Desert side of Otter Creek in 1870 (occupation listed as “Cod Fishing”), 33 in 1880 (“Fisherman”), and 10 in 1910 (“Lobster Fisherman”). In 2015, there is 1. These were all in-shore boats, not deep-sea. “While detailed records for 19th century Otter Creek are elusive, the official 1880 catch records for nearby Frenchman’s Bay (in Bar Harbor) is perhaps instructive of the diversity of species caught by early fishermen of Otter Creek. In that year, cod was far and away the predominant catch – its quantities representing almost 90% of the total 73 million pound catch reported for Frenchman’s Bay. Making up the remaining 10% of the catch, there was – in declining order – lobsters, hake, haddock, herring, mackerel, pollock, clams, and cusk.” [Deur]

View from Green Mountain by Sanford Gifford, 1865. That’s Otter Cove in the distance, full of boats.

The fishermen didn’t necessarily own the land the fish houses were built on. “In the 19th and early 20th centuries, land along the shore was not as highly valued and restricted as it is today, and landowners were less concerned about its use by fishermen. If a site was suitable for working (fishing), coastal land was generally viewed as available for use.”

The earliest deed to mention fish houses in Otter Creek was written in 1861, describing a property as “the lot of land on which he … now lives … together with fish house and shed on the shore nearby.” [Smythe] Deur raises some interesting points: “The partition of lots, beginning no later than the 1860s, perhaps reflected a collision between British common law traditions and Yankee legal standards relating to land ownership. References to fish houses on Otter Creek cove appear in deed records as early as 1861, … . Numerous references to fish houses then appear in deeds from 1868 through the end of the century …, suggesting that the exchange of legal title became commonplace at that time, and fish house lots were being partitioned accordingly … . It is unclear, but this timing and sequence of events might suggest that the first generation of fish house builders on Otter Creek cove were, after some 30 years of settlement on the cove, finally being forced to contemplate questions of succession for these informally ‘deeded’ fish house sites. … Perhaps significantly, some individuals were reportedly reluctant to engage in the process of securing deeds for their properties if there was no compelling need to do so, due to the expense, difficulty, and continued ambiguity over the veracity of individual claims.” That ambiguity and the informality of the fish house properties led to trouble in the 20th century …

So if the fish houses were so important that town staff helped maintain them, where did they go? Thereby hangs a tale! In short, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. had big plans for Otter Cove (remember the swimming pool and causeway in the last post?) and during the Depression, he bought up most of the land on the cove to become part of the National Park. The story is a lot more complicated and interesting than that, though, and I highly recommend reading the section in Deur’s book titled “Rockefeller and NPS Acquisition of Otter Cove.” It’s a pretty even-handed account of the conflicts caused by that process and the mixed feelings many locals had about Rockefeller and his work. Over the course of about 10 years, Rockefeller engineered the closing of local roads and the elimination of Otter Creek’s right-of-way to the water, and persuaded the Navy to move the Otter Cliffs radio station. Deur summarizes the controversies involving Rockefeller’s land acquisitions in Otter Creek, Appalachia and Wyoming, noting similarities between the cases and pointing out that he and his land companies were cleared of all formal charges but in all three cases the local communities remained alienated.

“Otter Creek oral tradition seems consistent on the point that Rockefeller used strong-armed tactics in these meetings to secure the vote to cede title to the landing. Some suggest that he packed these meetings with men who were on his payroll, providing transportation to and from the meeting from around the island. … While there was vociferous opposition from some quarters, the proposal to cede public claims to the right-of-way to the Otter Creek cove waterfront passed a March 3rd vote, effectively rescinding the Town of Mount Desert’s public right-of-way to the cove. In retrospect, some suggest that the community was truly divided as “about half the community was gratified to Mr. Rockefeller for the employment” and were not inclined to vote against him even without direct coercion.” [Deur]

Apparently there were legal challenges to many of these moves – I gather that among other things it is not legal to block a navigable waterway – and Rockefeller came up with a plan to allow fishing to continue in the cove while preserving the ‘wild’ look of the area. This was to consolidate the fish houses on the east side of the cove, and build an underpass into the Park Loop Road for an access road (it’s now called “Fish House Road.”) “He is reported to have traveled along the shoreline, providing “handshake deals” [to the fishermen] that he would not extinguish their access to the eastern cove and the fish houses in that location, provided that they would raise no further claims against the loss of rights to access on the inner cove and perhaps on the western shore as well … .” Even with all of this maneuvering, the title to the lands in Otter Creek was so complicated and ambiguous that it took years for the National Park Service to accept them. With all the headaches and misunderstandings they’ve had with the people of Otter Creek ever since, I’ll bet the Park’s early managers sometimes wished the land had stayed private! Deur notes: “While the NPS was not directly involved with Rockefeller’s transactions on the Otter Creek waterfront, the modern agency was the inheritor of the lands and the frustrations that came with them like some sort of ‘political encumbrance.’ The agency was at an additional disadvantage, because so little was recorded of what are reported to be Rockefeller’s “handshake deals” … Some kind of collision between park and resident interests was probably inevitable as Rockefeller passed from the scene and the NPS was left to manage these lands – acquired with considerable friction, no matter the legal ramifications.”

Contemporary attitudes have changed a lot since the early days of the NPS. National parks and even the concept of ‘wilderness’ are more widely considered to be artificial constructions, and “cultural landscapes” are now actively interpreted within the park system. See this post for an interview with Rebecca Cole-Will, Acadia’s current manager of Cultural Resources, who takes a much more inclusive view of working landscapes like Otter Creek than earlier generations of NPS managers did.

“A few interviewees suggest that, to Rockefeller’s credit, the waterfront dependence of Otter Creek may not have been clearly apparent at the time to Rockefeller, the NPS and other outsiders… . The houses and businesses, they note, were situated on the ridges above the cove by necessity, as the shoreline was steep and waves threaten most of the waterfront in storms. The practice of building fish houses below and ‘commuting’ the short distance between them had been seen as the most practical solution to these challenges, yet it left the waterfront looking sparsely settled and still quite “natural” by the standards of urban America. So too, many note that Rockefeller was a benefactor of great importance … to the communities of Mount Desert Island … . There were few arenas of Mount Desert Island life in which he did not exert some influence, reshaping the island to fit his expectations. Some appreciated his efforts, while others objected on complex grounds – that his actions had concrete and adverse impacts, or that they found the disproportionate influence of a single man on their lives to be profoundly distasteful. Despite even the conflicts between Rockefeller and some of the Otter Creek fishing families, some interviewees – descendents of these families – express enthusiasm for his acquisition efforts in preserving the cove shoreline. His legacy is complex; modern responses to it are even more so.” [Deur]

Right. So, messy history of a lovely spot. Back to the Coast Walk!

K: So you walk a mile?

J: I try to to. Sometimes more, sometimes less.

K: Where does this one end today?

J: I usually try and walk for about 2 hours. And sometimes that gets me farther, and sometimes there’s a great tide pool and I get nowhere because I spend like an hour at the tide pool.

K: You did it yesterday?

J: Yeah.

K: I thought you did it once a week?

J: Well, that was the original idea. But … sometimes it just takes a whole lot longer, so I go out more than once a week. But I find that, depending on the terrain, [after] two hours, I’m pretty darn tired. Yesterday, after doing 4 [hours on seaweed-covered boulders], I went home and … I lay down and I couldn’t move for the rest of the day. … I’m just trying to get a look at this duck-y little thing here. [Squinting through the camera’s telephoto lens.]

K: What are they?

J: I can’t tell. Maybe a guillemot? It’s black with a little white on the back of the neck.

K: It’s not a bufflehead, is it?

J: No. Oops, it went away. When it comes back up I’ll hand you the lens so you can take a look. Maybe you’ll have a better idea. … I’ve learned so many birds since I started.

K: You did? Neat!

J: Well my whole, I don’t know, natural history education is – I see something, I take a picture of it and then I figure out what it was. Because I don’t have any background in marine biology or birding or anything. Oh, there it is again, here, take a look. Oh, and it went away again.

[I finally got a good look at it when I enlarged the photos on my computer – it was a Surf Scoter.]

[I finally got a good look at it when I enlarged the photos on my computer – it was a Surf Scoter.]

K: This is natural, which is cool [gesturing to cobble seawall in front of us]. It seems to keep getting higher and higher:

J: Really?

K: Yeah. We were just talking about that, ’cause you’ll be sitting on the deck and you can barely see over the top of it now, … [but] we used to sit here and see the whole expanse. I mean, you can see it standing up, but sitting down…

J: I wonder what’s changed?

K: I don’t know. The number of storms?

J: Cause I would have assumed something like this got built up during the winter and then pulled back down a bit.

K: Right. Like Sand Beach.

J: Yeah.

…

J: Like I said, I am curious about what you find most interesting. Like what are your favorite stories and finds?

K: Probably, interestingly enough, just the opposite of the Park. I like the people stories. I like the stories about the people who lived here, … how they made their living, why that bar is there, what they burned in the lighthouse, in the tower.

J: There was a lighthouse?

K: The lookout tower. I love the natural beauty. And that’s why people came here. But I like the cultural impact that people have made on it.

J: Yeah, and I found it really really disconcerting, I had no idea about any of this, how thoroughly it’s been erased. Like walking around here, you’d never know there was a town right there, and that there was all this amazing colonization of the landscape. I want to see more of that. I like the old pilings. I mean, that’s, frankly, the old pilings are what started this whole thing. It was the remains of the herring weir off Bar Island. If you go out at a really low tide, kind of just off the Bar, there are these stubs of posts that stick out maybe six inches, and they’re obviously in straight lines, but they couldn’t possibly have been a dock, just from where they are, and I wondered about them for years. You know, what the hell are these? And then a couple of years ago the Bar Harbor Historical Society posted a photograph of the Rodick herring weirs.

Photo from the Bar Harbor Historical Society Facebook page

K: Oh! And you went

J: I went, ‘Oh my god there’s so much I don’t know!’ Starting with, ‘you mean herring came inshore?’ There’s no herring in the harbor now. Just the scale of change.

K: We got herrings, and then we made pickled herring.

J: Yum, that’s one of my favorite things. Herring in sour cream sauce.

K: Yup, exactly!

J: So where did you catch it?

K: Dennis came home with the herring. I don’t know if someone gave it to him. We had done it previously with pickerel, which is not my favorite fish at all, and I found a cream [recipe] because my dad, he loved pickled herring. We had all these pickerel, just wanted to try it, so we did, and it was amazingly delicious. Not quite so salty-vinegary. We brined it for days, then pickling spices, and rinsed it and packed it with vinegar, peppercorns, allspice, juniper berries, dill, and cream.

J: That sounds amazing.

K: And now we’ve got six jars in the refrigerator.

J: You’re making me hungry!

K: I had some for breakfast, actually!

J: Oh that’s great. … My grandmother used to make black bread – we’re Baltic, so pickled herring [with] kind of a rough, black, crusty bread – heaven.

K: I have no idea how we’re going to get up to the land again from here, you know.

J: Well, sometimes I can get up, sometimes I have to go back.

K: I know this is very steep, because Blackwoods … there are benches up there, and there’s a little in between where the benches are, … [there’s] a place where otter live, it’s like an otter den, and otter paths and scat and all of that. They’re freshwater, they’re not sea otters, but they happen to live next to the ocean.

…

K: So what do I love about this place? Hmm. I just love the people.

J: I know. Besides the amazing community and the stunningly gorgeous landscape, what do you love about Otter Creek?

K: The history of food, old recipes…

J: Otter Creek recipes?

K: Not terribly old, but you know, women’s club things, jello salads and [inaudible]

K: I’m going to have to get down and crawl.

J: In some ways winter was easier going through landscapes like this, cause it was all frozen and I had creepers on.

K: Good readership?

J: I think so?

K: I see more people referring to your project, which is great.

J: A lot of, like the historical societies and Friends of Acadia are sharing the posts on Facebook.

K: Wonderful.

J: So I don’t even know how many people are actually reading it. Because I can’t track them.

K: You can’t? What is it, WordPress?

J: It’s WordPress and I have it set up with Google Analytics, but I can’t quite figure it out.

K: There’s something called Jetpack, it takes about 20 seconds to put on, it may not be as complicated, it may not give you as much information as Google Analytics – it comes with all the Bangor Daily News blogs, and I ended up putting it on my site. It gives you site stats, tells you how many per day, where they were coming from, if they clicked on any of your links, outgoing; it’s minimal but it lets you know.

J: Yeah. Google Analytics is almost too much, I can’t quite follow what they’re telling me.

K: I’m going to try and go [up the rocks here.] Mmm, maybe I’m not. Want to give me a push?

J: Yup. [Karen climbed up a steep incline to a shelf of rock.]

K: Oh, but how are you going to get up?

J: I’ll get up. You got it? I’m going to send my camera up first, though. The camera really slows me down. [I passed her my camera and awkwardly scrambled up after her.]

K: I would imagine!

J: But, it’s kind of the whole point, so… There are plenty of times I have to put it in my backpack and climb. [Karen extended a hand.] I’d rather not pull you over! Got it!

K: Excellent!

K: Are you going to walk the cliffs in Seal Harbor?

J: Yup. I’m working on getting permission.

K: Do you know where the Maine Coast Heritage Trust has a path that goes down off of Cooksey Drive?

J: No, I know they have a property there, I didn’t know there was a path.

K: Yeah, there’s a path that goes down to the water, perfect for sunrise yoga, one of my twelve spots, but if you’re down at that point and you look to the right you might see something white …. Take the time to walk over to it because it’s the beginning of the biggest quartz intrusion that we have on MDI, and it goes for almost two and a half miles. Dennis and I have followed it – you can’t follow it because you walk into property problems – but we’ve seen it and picked it up and seen it and picked it up. At that one particular point, it’s about this big. And it’s white.

J: OK, and that’s on the Maine Coast Heritage property?

K: It’s actually on the private property, there’s a borderline there. I mean you can get close enough to get a good photo of it without actually stepping on the property.

J: You know, one thing I’ve found really interesting is, all of the tourist spots on this island were private property. Anemone Cave, Schooner Head, Great Head … but they were still popular tourist places and people went there. And I’m so curious about how that worked.

K: Different attitudes. Not ‘mine’ but …

J: Yeah. It kind of reminds me more of the British walking trails, which I know very little about, but they go over private property but they’re [ancient] and people still use them.

—-

K: I’m still thinking about your question about what do I love about it here. What do I find satisfying? It meets needs in so many ways. I mean we have a garden, but we also do a fair amount of foraging and gathering and hunting and fishing. Our grocery bill is pretty minimal. We have a root cellar… we’re just now finishing the last of the carrots and vegetables and potatoes. Which is perfect because now we’re about to plant and get …

J: Get the next round

K: And I do want to know about this bar.

J: Who built it?

K: Yeah.

J: It seems like that would have been quite the undertaking.

K: I don’t even know how old or how long it’s been there. When did the Conservation Corps do their work?

J: 30s?

K: That would have been a perfect Conservation Corps [project], the harbor – [inaudible] kind of shaped the harbor to begin with. That could have made it.

J: Yeah, but they left a lot of records.

K: Ahh. But maybe it’s there in the records and nobody’s ever looked.

J: Oh, yeah. That’s a good question. See, when I asked the Park archivist, I just said I was interested in the Otter Creek area, and the way it’s organized is by sort of as the collections come in, they’re kept as a collection, so I got the sense it was a little hard to find [certain subjects], but if you said you were specifically interested in the CCC activities here she might be able to help.

K: I’ll add it to my list.

J: And of course those records might be in DC. Field trip! I love poking around in archives. It’s the serendipity. Oh you would have loved this. So she brought out these random boxes of photographs

K: Careful up here, this is super slippery.

J: Okay, whoa! [My feet went right out from under me and I sat down abruptly on a squashy mass of rockweed. Whoops.] … And I’m not sure what the collection was. It seemed like it was all one person’s photos.

K: That’s kind of cool.

J: And I’m guessing it was someone who was a ranger or attached to the Park. Whoa. I’ll talk when I’ve gotten through this. [It was another thick patch of rockweed.]

K: Yeah, that one stretch is tricky.

J: Okay, so it was a collection of photos mostly of birds and animals around the island. Really good ones. Like somebody who really knew their stuff. Pictures of wild seabirds that had just hatched, or sitting on their eggs, ‘kildeer on nest’ kind of thing. And those were cool. But then, so there was a picture of ‘ravens in nest.’ Ok that’s cool. So the next picture is titled ‘Sully photographing the ravens’ nest.’

K: Who?

J: Sully. It just says Sully. I think it’s short for Sullivan, ’cause there’s a Sullivan who shows up later. I’m pretty sure it’s the rocks on Hunter Point and the ravens, it turns out, are on a cliff, like two-thirds of the way up, and it’s a cleft in the rock and Sully is perched with a tripod on the other side of the cleft.

K: Nice. Wow.

J: Yeah but then, next photo, ‘Banding ravens.’ So, there’s two guys, one’s on the top of the cliff with a rope, and the other guy is dangling getting down to the ravens’ nest and there’s this whole series of pictures of him clinging to the cliff wall, standing on the ravens’ nest while the ravens are there. Those are going on the blog!

K: Wonderful.

J: Yeah, as soon as I get to Hunters Point those are going up. That’s what I mean by serendipity. But it takes time.

Here’s the photo of the raven chicks; I’ll show you the others when we get to Hunters Point. Photo courtesy of Acadia National Park archives.

K: Which cliffs? Because there’s a ravens’ nest that has had ravens for over a hundred years until somebody bought the property and did some changes and they’ve been gone now. But I would bike out and watch them put the twigs in, because every year it decomposed, get the deer fur and line it, and then lay the eggs, and sometimes there was snow on top of them, and then the eggs would hatch. I was there once when I saw a head open the shell, great big eyes, all you saw was these big eyes, and then we would watch them until they grew until they were like sardines in a can, and then when they were teenagers they could barely fit in the nest. And that’s when I realized well, that’s why the nest doesn’t last to another year, because they got so big they started pushing it…

J: Oh, they sort of burst out?

K: Yeah, it didn’t have its integrity so much anymore. And then they were gone.

J: Wow.

K: That’s on Cooksey Drive, and where’s Hunters Beach in relation to that? I mean, the ledge is, there’s still remnants of the nest there.

J: Darn, I was hoping to see ravens when I went round.

K: Well, this may be a different nest. [Some of the photos have ‘Hunters Point’ in the title, which is the point of land between Hunters Beach and Little Hunters Beach, so they are not in the same location as the nest Karen saw, which was off Cooksey Drive.] … You can just drive down Cooksey Drive and look at this place. The estate is called Raven Ledge, imagine that.

J: And then of course they chased the ravens away. You know there’s an old joke that developments are named for the animals they drove out?

K: [laughs] Oh my god that’s so true isn’t it?

J: Orchard Estates, Fox Run.

K: Ouch.

J: … It’s kind of black humor.

K: Yeah. This looks like a relative easy up, and I may just do that, because past that rock it gets really steep. Are you going to keep on going?

J: I am.

But we weren’t quite ready to part yet, so we sat on a ledge, soaking up the spring sunlight, and chatting a little longer. It got so warm that my iPhone (which I carry pinned to the front of my coat in a black sock to record these conversations) overheated and shut down!

This one’s a crow, not a raven. Raven tails are more diamond-shaped. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a raven in the wild, only at the Tower of London.

K: Are you meeting with somebody to go around that point?

J: Oh, next week? Yeah, Brian Reilly.

K: Who’s that?

J: He’s an environmental consultant, and I’m blanking on the name of the company he works for.

K: Cool, how’d you meet him?

J: He’s friends with Anne Krieg, so we met at a party. And I think he’s working with Frenchman Bay Partners.

K: I don’t know who they are?

J: Jane Disney? Most people know her for the eelgrass studies and water quality? She’s at the Bio Lab.

K: OK.

J: The Frenchman Bay Partners is like a loose consortium of people who are concerned about the Bay, and they’re doing studies on mudflats, clam populations, eelgrass, and they’re also doing long-term I can’t remember what they call it, they’re … talking to all the different constituents for the Bay, like the tour operators and the fisherpeople and the tourists and people who live here, trying to prioritize what’s important. And then come up with a long-term management plan for the Bay.

K: That’s what I love about the Coast Walk. It mixes so many different things, from intimate personal tales to the big picture of the coast and its dynamics.

J: Sometimes my brain gets full.

K: I don’t feel like I’ve shared enough about the fish houses, which is what you wanted to talk about. The majority of them were over there. And I’ve got some beautiful paintings of them by Thelma Wass who was married to one of them. I could give you that if you had any interest in scanning it.

J: I do, actually.

It didn’t look like our schedules would allow a meet-up to look at Karen’s archives before it was time to write this post – too much prep work for the summer rental season for both of us –

K: We’ll do it anyway, even if it doesn’t work into the blog.

J: That’s true, cause I can add it back. I’ve actually been going and adding things, because the more I do this I find things… because I’m writing a book, you know. The blog isn’t the end of it.

K: Wonderful!

J: My friend Kelley [says] this needs to be an app, so when people come here, and they’re like, ‘what’s at Otter Cliffs?’ they bring up the Otter Cliffs portion of the [app]…

K: oh my word

J: So she’s looking into that. How one does that.

K: Oooh

J: Wouldn’t that be cool? So … whenever I find stuff I add it into the portion of the blog I’ve already written.

K: So the fish houses were there until the 1960s. 1961 the Park decided they were an eyesore and they were on Park property. So I’m not sure if they tore them down or burned them down, there was a lot of real unhappiness about this. And a couple of people picked theirs up and physically moved them. Other people left because they didn’t want to be here when that happened. After all was said and done they got in trouble. So for people who asked they rebuilt.

J: The Park got in trouble?

K: Yeah. They didn’t have permission to do this, whatever. I don’t really know all the details. All I know is that Mike Bracy, whose fish house was down there, got a new house from the Park, but he was so mad at the Park that he didn’t want to be here because everybody else was gone, so he picked it up and moved it to the woods in Otter Creek where it is to this day.

J: It’s on your map, isn’t it?

Detail of “The Village of Otter Creek,” hand-drawn map by Karen Zimmerman. Available here.

K: Yeah, Mike Bracy’s fish house. Why is there a fish house in the middle of the woods? Because Mike Bracy didn’t want it down here. Nobody was fishing down here anymore. So it turned into his cabin in the woods.

J: Can’t really blame him.

K: He’s somebody I want to write a story about but there’s so much I’m intimidated by it. He talked with animals and he fed beavers and he was about this tall [with a] shock of blond hair, graying hair, his sweaters were always frayed and he mumbled to himself all the time. So he was one of those people I didn’t really connect with all that much when I first moved here. And Dennis thinks he had Alzheimer’s or something near the end. But when he died, they had the funeral in the cemetery across the street from our house, and Dennis was there and all these people gathered around the casket, and a young deer comes out of the woods, walks over and stands there among the crowd at the service and somebody reached out and the deer let him pet him and the deer kind of walked around and lots of people petted him. Dennis took photographs of this young deer at the cemetery at Mike Bracy’s [funeral], and it was one of the first things he showed me because it’s one of the stories he likes to tell. And then of course our house burned down and in it went the scrapbook with all those photographs that nobody had thought to scan … . Did you see the house after it burned?

J: No.

K: It was just … black chimneys and occasional black hunks of wood. So we were in there with our suits on, because there was still [some] stuff but it was totally sodden, and there was a piece of an old bookcase. So we lifted the bookcase up, and [there was a] pile of my clothing drenched with goopy stuff, so we pulled that away and underneath was the photo album, totally black, scorched around the edges, but there were the pictures of Mike Bracy.

J: Oh my gosh!

K: So they survived the fire, unbelievably survived that fire. … So that’s part of the Mike Bracy story.

J: So why are you intimidated about writing about him?

K: Because every time I talk to somebody about it they say, ‘oh, do you know all this about him?’ And it’s like, ‘no, I didn’t know that.’ ‘Oh, ok.’ ‘Do you know all about him going to the Philippines?’ and they keep telling me other things that I have to include. And he had … it’s kind of like Stevie Smith in a way, I guess he had a huge following of people who really liked him; he had a run-in with one of the Rockefellers and another one hired a plane to come up and have him take them up to the beavers, maybe it was Peggy, I’m forgetting all this stuff, so I have to do the research to find out: alright who was it who came up with the plane and went down to … see the beavers with Mike Bracy? There are two pictures of Mike Bracy in Jordan’s breakfast place, because he used to go in there for breakfast every morning.

J: You really need to write this! He sounds amazing.

K: I know, I do need to write this, but …, in the meantime, take whatever you want of it. And that’s part of why I love Otter Creek, I guess. Because everything you tug on is connected to this whole giant world of things and sometimes you can follow them and sometimes you can’t because there’ll be another one tugging on you and ….

J: I’m finding that about the whole island. Here’s an example. You know the post I did on Sand Beach with the movie photos?

K: Oh, yeah!

J: So there was a picture of a young girl looking grumpy, which I thought was hilarious. Turns out that’s Tasha Higgins’ great-aunt. And so Tasha’s looking up what became of her. Apparently she became a nurse in the Navy. And Tasha said she always sent each of her great-grandchildren a dollar on their birthdays.

K: Aww.

J: So that’s like, when I say I need to add things back in, that’s going to get added in when Tasha gets a little more [info.] But I’ll bet you if we write something about Mike Bracy we will get so much stuff about Mike Bracy, especially if I say that you want to write something. Do mind if I do?

K: No, of course not!

J: Well let’s do it! It’ll be like an ad for information.

K: I put a picture out of somebody at the fish houses, it was taken by, oh famous photographer from the fifties, he was kind of a swashbuckler guy, I know you know him. Oh, he did a whole mass of black-and-white books, Downeast Maine, The Maine Coast,

J: Sarge Collier?

K: Yes! Thank you. So he did a photograph of a woman at one of the fish houses.

J: I’ve seen that! And she’s in a dress and totally like [strikes a pose] … yeah.

[Both laughing]

Photo by Sargent Collier, ca.1950, from Karen’s blog

K: And I asked everybody I knew, nobody knows who this is, so I put it on and the story was about not knowing who this person was, and it wasn’t up for an hour and somebody told me who it was! Wow. So I had to go back and write ‘Editor’s Note: by the way, we now know who she is.’ The identical picture is in the Manor House on West Street, and Stacy Smith who owns the Manor House inn grew up seeing that picture, and it was her girlfriend’s mother. … Stories within stories with stories! Aren’t they wonderful?

And then it really was time for Karen to head in to her office, so she scrambled up the rest of the cliff to the Park Loop Road, and I continued on.

One of the first things I noticed once I started focusing on the details around me was the change in the the velvety, bright green marine algae covering the rocks. Back at Otter Point, Chris Petersen had pointed out that the periwinkles were eating it, and by late June it would all be gone. First I noticed patches like this, where the periwinkle had surrounded it and were munching inward:

And then I found even more patches like this, where they had fed along cracks in the rock, and then struck out across the fields of seaweed like little lawnmowers.

Then I got distracted by things swimming in one of the higher-elevation tide pools, and spent a good fifteen minutes trying to get a good shot of this:

After a whole lot of research the only thing I can say for sure is it’s some kind of amphipod. After that I worked my way down to the tidepools close to the low tide line. The area was completely encrusted in barnacles,

After a whole lot of research the only thing I can say for sure is it’s some kind of amphipod. After that I worked my way down to the tidepools close to the low tide line. The area was completely encrusted in barnacles,

which made kneeling for photographs kind of painful.

which made kneeling for photographs kind of painful.

The light was good, though, so it was totally worth it. Often the sunlight is from above, and the glare on the water surface obscures everything in the pool, so when I get sunlight coming in from the side, like this

I rejoice.

The lower areas of this tide pool were completely encrusted in a pink crustose coralline (Lithothamnion maybe?) that was also covering the horse mussels and limpets.

I looked up from this tide pool just in time to see an enormous flock of something fly overhead and land far out in the bay.

After blowing up the photos on the computer as far as possible and staring at the little details ’til my eyes went blurry, my best guess is they were:

After blowing up the photos on the computer as far as possible and staring at the little details ’til my eyes went blurry, my best guess is they were:

more Surf Scoters? Black Ducks? No idea, sorry, they were too far out to get useful shots, which was really annoying since it was the biggest flock of anything I’ve seen in years.

more Surf Scoters? Black Ducks? No idea, sorry, they were too far out to get useful shots, which was really annoying since it was the biggest flock of anything I’ve seen in years.

Soon after that, I reached a deep cleft in the shore and had to scramble up the cliff to the Park Loop Road. There’s a nice lookout point near the path to the campground there, and I sat on the benches and looked ahead to the beginning of Coast Walk 12:

Up on dry land, signs of spring were everywhere. Even the junipers

Everything was budding and leafing and bursting into flower:

but by the time I’d walked all the way back to the Causeway, where I’d left my car, my legs were wobbly with all the squatting-by-tidepools and climbing-of-cliffs, and I was more interested in a hot shower and a nap than the glories of springtime. As usual. And also as usual, by the time I reach the end of one of these posts, I’m all talked out!

Next we head towards Hunters Beach with Brian Reilly. It take me about 40 hours per post to edit photos, transcribe interviews, research history, identify plants or animals, and just plain write. Let’s see if I can get this next post done by Christmas!

Hi Karen,

Loved everything you had to say and all of the pics. I’m sold on coming up to Maine soon anyway. My friend will be moving there soon to Eastport this spring. And I plan to visit her there and do lots of camping out, fishing, and etc., through out the state. Otter Point will be included in one of my many destinations of Maine. Thank you for all of your walks, hikes, and squats you do for the perfect shots. I have thoroughly enjoyed all of the pics and reading about Otter Point. And thank you so much for the share. Blessings to you.

Hi Lori,

Stop and visit on your way! We love Eastport, what is your friend going to do there? Photos in this blog by amazing photographer Jennifer Booher. Hope to see you, and thanks or reading.