“Ranger talking to campers,” Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Acadia National Park, Catalog #ACAD 29258

May 27, 2015: noon-3pm. 71 degrees, sunny, strong breeze, light clouds.

Walker: Brian Reilly, Senior Consultant – Natural Resource Assets, Cardno

On a gorgeous morning in late May, Brian Reilly and I parked at the Blackwoods Campground (a perk of being an Artist-in-Residence) and started strolling down the camp road to the shore. We’d met a couple of times, once through the Frenchman Bay Partners and again at a friend’s party, but all I knew was that he was an outdoorsy person doing something vaguely environmental for a living. Brian turned out to be a strong and adventurous hiker, which was a good thing given the steep terrain we found on this hike!

Before we start the narrative proper, while Brian and I are still wandering around the access roads looking for the path to the shore, let me fill you in on my research. [My main sources were: Cultural Landscape Report for Blackwoods and Seawall Campgrounds, H. Eliot Foulds, Acadia National Park, National Park Service, Boston, 1996; and Presenting Nature, The Historic Landscape Design of the National Park Service, Linda Flint McClelland, National Park Service, 1993.]

Image from Foulds, Cultural Landscape Report for Blackwoods and Seawall Campgrounds, 1996.

The first public campground on MDI was on Bar Harbor’s Athletic Fields, down at the end of Ledgelawn. Before it was either the Athletic Fields or a tourist campground

Image from Foulds, Cultural Landscape Report for Blackwoods and Seawall Campgrounds, 1996.

it was one of the last Wabanaki communities on the island. This is where they went when development pressure drove them off their traditional campsite above the Bar (we talked about that on Coast Walk 1.)

Image from Foulds, Cultural Landscape Report for Blackwoods and Seawall Campgrounds, 1996.

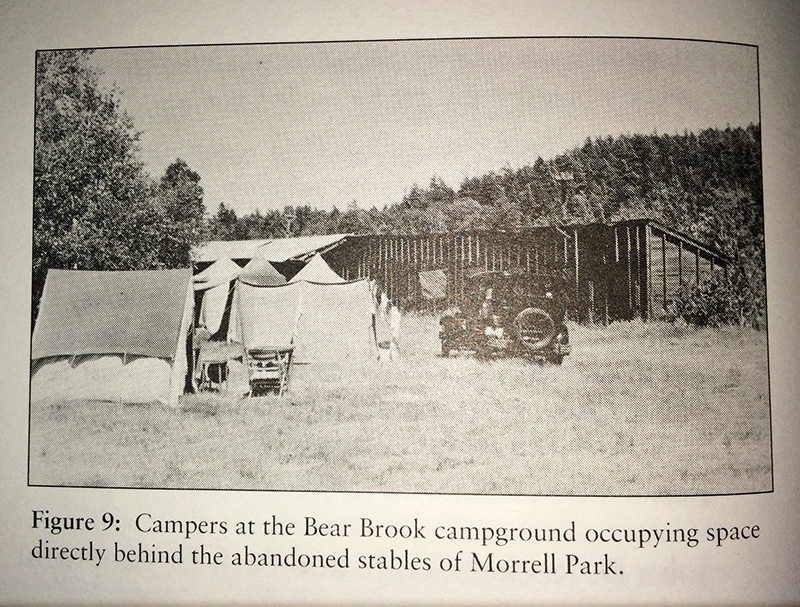

For various reasons, mostly aesthetic, the Park (aka George Dorr) developed a public campground, this one officially part of Acadia, near the old racetrack at Robin Hood Park (also called Morrell Park) around 1927. According to Foulds, Bear Brook was “typical of national park campgrounds of the 1920’s, … campsites and parking were provided randomly at the edge of clearings or in areas where the forest understory had been removed.” Basically, you drove in, parked next to the road, and pitched your tent wherever looked reasonably flat. You know how my mind always boggles at some point during a Coast Walk? Coming right up…

Image from Foulds, Cultural Landscape Report for Blackwoods and Seawall Campgrounds, 1996.

Those random campsites in all the national parks led to – surprise – cars parking on tree roots, compacted soil, dying undergrowth, erosion, and general deterioration of the camp area. E.P. Meinecke, a forest pathologist with the Park Service, analyzed a lot of these failing campgrounds in the late 1920s, and came up with a series of recommendations.

This is the mind-boggling moment. Picture a car-accessible campsite – any campsite, pretty much anywhere in the world. There’s a place to park; there’s a relatively flat place to pitch your tent; there’s a place for a fire; and there’s usually a picnic table. That didn’t just happen. It was designed. By E.P. Meinecke. In the late 20s. I don’t know about you, but I totally take campgrounds for granted. Like toothbrushes. Or wheels. They just seem sort of obvious, and it’s really weird to imagine a time when they didn’t exist. Meinecke’s ideas were codified in the Park Service design manuals and incorporated in all NPS campgrounds from that point forward, from which they spread pretty much everywhere.

Image from Foulds, Cultural Landscape Report for Blackwoods and Seawall Campgrounds, 1996.

Before Meinecke invented the campsite (and why, we should all be asking, is there no E.P. Meinecke Day celebrating this?), you just pulled over and camped wherever. Because see, before the 1920s, car-camping didn’t exist. For the most part, only wealthy people could afford to take a train out to a National Park and stay in the hotels there or hire a guide to take them out to the back country. Then cars became common in the middle class, and suddenly everyone could get to the parks. And in the early 1900s, the Fresh Air movement, the Boy Scouts, the Girl Scouts, the YMCA and Teddy Roosevelt had all spread the popularity of camping and outdoor activity. So you had a lot more people wanting to camp, with the ability to reach the parks. Which was awesome, but also a conundrum that the Park Service is still trying to solve: how do you provide access for everybody (which is part one of the NPS’s basic mission) while preserving the resource (which is part two)? [P.S. You can read more about Meinecke and campground development here.]

Image from Foulds, Cultural Landscape Report for Blackwoods and Seawall Campgrounds, 1996.

Anyway, in 1932 Bear Brook was renovated using Meinecke’s principles. Poking around in the Park archives, I found a letter from the 1934 campground ranger setting out all the details of his job – how to welcome campers, when he allowed campfires, organizing talent shows and naturalist programs … it’s awesome!

At the end of the letter was this tally sheet of all the campers in 1934 showing profession, annual income, how they arrived – all kinds of stuff! Looks like most campers in 1934 were “professionals” (I assume they mean doctors, lawyers, and so forth) making more than $2,000 a year, on their annual vacation, which was two or three weeks (practically nobody checked the ‘one week’ box), and arriving by car. Cool, huh?

Photo courtesy of Acadia National Park Archives; “September 13, 1934, Report of Campground Ranger for summer season 1934″, Box 74 , folder 3

Photo courtesy of Acadia National Park Archives, Catalog #ACAD 29539

I found the photo above in a fairly random box of photos in the ANP Archives. It was only labeled “Hikers on Lookout over campground.” I think it must be Bear Brook, because there’s no pond at Blackwoods and I can’t think of any big hills around Seawall. The Bear Brook campground was closed and converted to a picnic area by 1962. And I think that’s probably plenty of time spent talking about a feature that isn’t even remotely on the path of the Coast Walk! Let’s get back to Blackwoods.

Blackwoods trivia: The earliest map I’ve seen that names this area (1893, above) calls it “Dark Hill.” I read somewhere that it was named for the spruce forest that covered it, but I haven’t been able to find that reference again. By 1911, it’s labeled “The Black Woods:”

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who has snuck into pretty much every frickin’ post since we rounded Otter Point, financed a private campground here that opened in 1926. According to Foulds, “Another subtle yet important political benefit of the Blackwoods site was the campground’s isolation ‘from the finer residential sections of the summer people’ which were located near Bar Harbor and Seal Harbor.”

The country sank into the Depression years, and when FDR took office there was a flurry of activity that resulted in two Acts directly influencing our story. The first, the Federal Emergency Relief Act (FERA), which was designed to help families move off Dust Bowl lands, started designating “submarginal lands” (in order to help people escape them.) In one of those rare moments of bureaucratic brilliancy, FERA ordered the Park Service to find any recreational potential in those submarginal lands, which were to be developed as “Recreational Demonstration Areas (RDA).” Guess where Blackwoods and Seawall came from?

“Pulpwood operation at Blackwoods.” Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Acadia National Park, catalog #ACAD29539

The second was the establishment of the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1933. MDI got two CCC camps right away – NP-1 was set up in May of 1933 on McFarland Hill in Bar Harbor, and NP-2 was set up on Long Pond in Southwest Harbor in June. They started work on the Bear Brook renovations in 1933 and on Seawall in 1935. Finally in 1937 the CCC started surveying and clearing land for the Blackwoods campground.

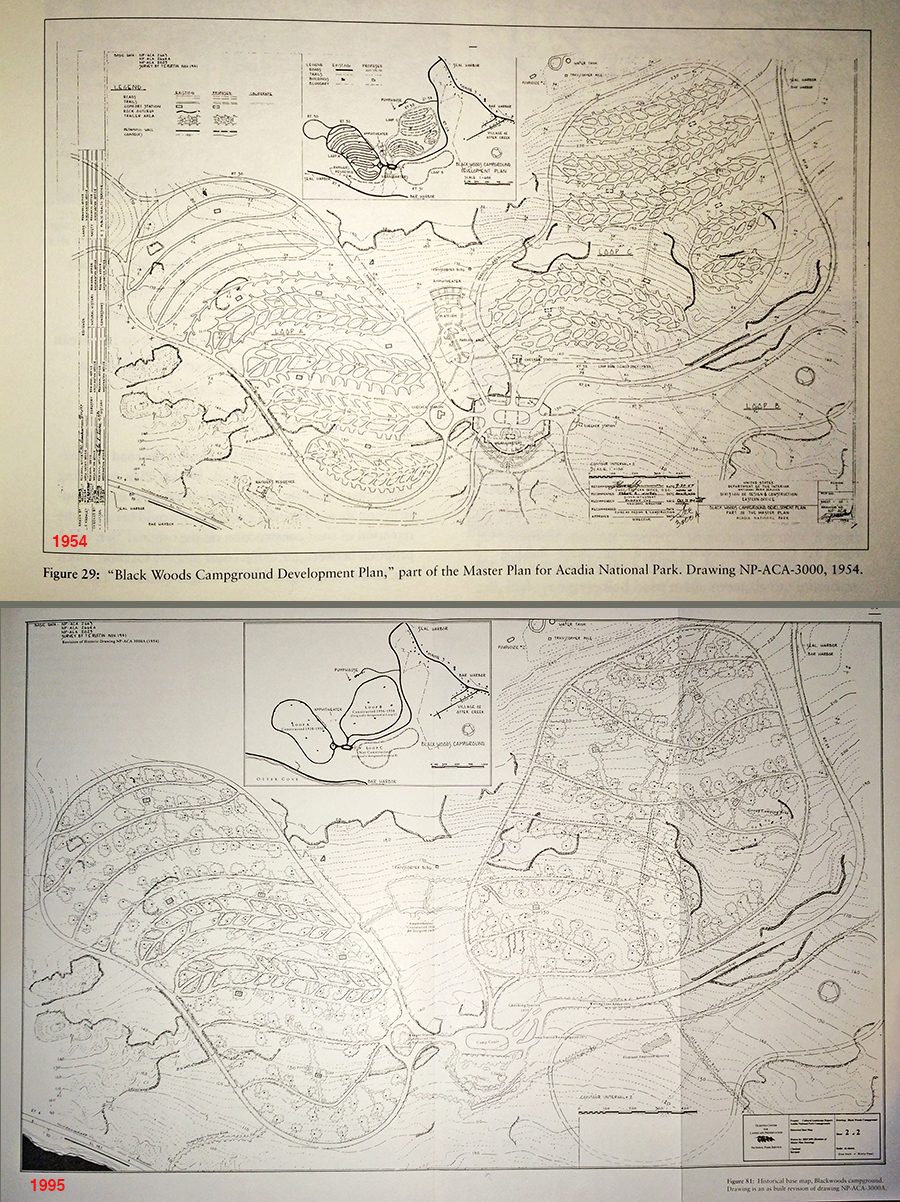

Images from Foulds, Cultural Landscape Report for Blackwoods and Seawall Campgrounds, 1996.

Blackwoods’ early layout was planned to accommodate trailers as well as cars. Rather than a spur for parking a car, Blackwoods sites used “bypass” and “link” designs which allowed the car and trailer to drive off the camp road, park, and drive back on without turning around. The initial plan was ambitious, and would have provided about 400 campsites (Seawall only had 63) and much of it was never built.

When World War II broke out, it diverted funds and labor away from the CCC, construction slowed, and as gasoline rationing was imposed, tourism declined as well. When the CCC in Acadia was disbanded in 1942, Blackwoods was not operational. Campground construction basically stopped, resuming after the war when tourism surged again. Blackwoods’ Loop A finally opened to the public in 1946, and the Fire of ’47 promptly redirected all park money and personnel to clean-up. In 1949, only the Bear Brook and Seawall campgrounds were being publicized. Over the next few years comfort stations and the amphitheater were built. In 1956-61 the second campsite loop at Blackwoods was built, abandoning the bypass-style campsite for the spur type – you can see the changes comparing the design with the as-built in the plans above.

Image from Foulds, Cultural Landscape Report for Blackwoods and Seawall Campgrounds, 1996.

“President Eisenhower appointed the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission (ORRRC) in 1958 … . The ORRRC was given the broad charge to propose a national agenda for outdoor recreation and conservation … The sensitivity of the ORRRC report toward private vendors of recreational services and opportunities, may explain why bathing and laundry facilities were not developed at either campground … . Although these facilities were originally planned as a part of campground development, local vendors of campground services had filled the vacuum caused by the lack of on site facilities during the postwar vears.” And so the Otter Creek Hot Showers are still with us.

Image from Foulds, Cultural Landscape Report for Blackwoods and Seawall Campgrounds, 1996.

Although most of Blackwoods was built post-war, the remaining pieces of the CCC installation qualified it for the National Register of Historic Places: Loop A, “five historic comfort stations,” the entrance drive, and the camp court. [Foulds, 1996] Is anyone else juvenile enough to giggle at the idea of historic toilets?

Maybe I should just get back to the day’s travels…

“Blackwoods campers with string of pollock.” Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Acadia National Park, Catalog #ACAD 29258

Brian: I hardly ever come in to Blackwoods

Jenn: No, me either. I’ve been here once for a Boy Scout campout.

B: Yeah, that’s why I’ve been here. Now you’re not a Boy Scout?

J: No, I was a Den Mother. My husband was actually a leader, what do you call it

B: Pack Master, Pack Leader

J: Yes, Pack Leader. This was Cub Scouts. We didn’t make it to actual Boy Scouts.

B: That is so too bad, because, so I was a Scout Master, I was a Cub Scout, I was an Eagle Scout, or I am an Eagle Scout.

J: Awesome! No kidding.

B: I was a scout leader in Illinois when we moved here, Cub Scout, and then when we moved here became a scout leader in Northeast Harbor. And I was the scout leader for many years in Northeast Harbor and now I’m actually still involved in the district. … I’m the committee chairman. And it’s so too bad, because so many kids get burned out in Cub Scouts, that they don’t go on to Boy Scouts. And Cub Scouts is great but Boy Scouts is so much more fun.

J: Well, how should I put this, Christopher made it into Boy Scouts, and was still having a good time but there was that whole thing with homosexuals [a controversy within scouting leadership about whether gay youth and leaders should be allowed to participate], there was that whole flare-up, you know, five, six years ago? And the leadership of the troop in Bar Harbor had very different opinions about that than Brian and I did.

B: Oh, okay.

J: And we didn’t actually have a falling out with them, we tend to be somewhat diplomatic, but it cut down on my personal enthusiasm for the whole organization.

B: Sure. That’s too bad. … And I don’t know what your beliefs were or anything, I know that when we started the troop in Northeast Harbor, so I re-started the troop, … and remember I was From Away, right? So I’m the guy from away who’s starting a Boy Scout troop, they don’t know me from Adam, so I had to kind of call up and chat with the guy who ran the troop before me, Bill Ferm, wonderful guy, and he basically asked me what my thoughts were on homosexuals and religion in Scouts. And my personal opinion was I didn’t care. I don’t care. You believe in what you want to believe and as long as you respect other people’s beliefs, there you go. … And he said, ‘Great, here’s the key to the, here’s the checkbook,’ basically, and there you go.

J: That sounds a little more inclusive. Our troop actually had a disagreement with the Congregational Church and moved over to the Baptist. That was the point at which I started feeling, ‘It’s okay if you don’t want to go to Boy Scouts anymore.’

B: I don’t care. As long as the boys, [you] teach them to respect other people’s opinions and to respect other people and to respect themselves and have a good time.

J: That’s where I am. I don’t think people need to be left out.

B: Oh god, no! No, we didn’t leave anybody out. We were very inclusive. And then we had some people who were very religious and some people who were very atheist. And that was a delicate balance. Cause the religious people would like to say a prayer and we had to respect that, but then we also had to respect that we couldn’t go over the top. And you know there was a little bit of checks and balances on the leader’s part. We had to make sure that everyone felt included.

J: That sounds like a much more sensible approach.

B: Yeah, we were kind of a non-typical troop.

J: Yeah, it’s a shame because it’s a great organization.

B: But we took all the boys in, half of them became Eagle Scouts, no one’s in jail.

J: That’s how you know you’ve succeeded, right?

B: That’s where I’m at!

J: I was a Girl Scout. I was a Girl Scout up until, I made it through the Junior level. [Nope, I was a Cadet when I stopped.] But then I went to a different school and couldn’t make the meetings anymore or I would probably still be a Girl Scout.

B: I liked the Boy Scouts. When I was a boy … I went for a time when we had a bad leader so I dropped out for a while and then I joined a different troop. We went camping, like wilderness camping, white-water rafting; the troop that we had here, we treated it like a high adventure troop, so we didn’t have a trailer, we never car-camped. If we wanted to go camping we carried everything on our back. We hiked in several miles and we went camping.

J: Awesome!

B: They didn’t like Camp, they didn’t like Boy Scout Camp because it was too programmatic, so when we went camping, like for our long term camping, … we went down the Allagash for a week, or we went and hiked the AT for a week [ed.note: Appalachian Trail] and that was our Boy Scout Camp.

J: That’s amazing.

B: Yeah. So I kept the boys in all the way through senior year of high school. From 5th grade through senior year of high school.

J: That should go on your résumé. That’s like a life achievement.

B: We had great, great kids so it made it really easy. God, look at this weather!

J: So this is where I stopped last walk, and it looked like we had a series of outcrops and then small bouldery beaches coming up.

B: OK. Do we walk down at the water? You’re the leader, I’ll follow you.

J: Usually I like to get down as close to the water as I can, but scoping this out, let’s just see. I also know that in this kind of terrain I have got about two hours of energy. So. It looks like there’s a point there where there’s like a bouldery beach kind of thing. I’ll bet it would be easier to get down right there, so let’s walk along the top right to there and then go down and then go along the shore from there. Plan?

B: Plan!

B: … We could go that way and that would get us closer. We couldn’t go that way anyway because there’s a giant, um,…

J: Cleft?

B: Yeah

J: Yup. We could go around the outside, it’ll be easier.

J: Hey Brian, hold on. Sorry. The camera slows me down a lot. … [Sounds of scrambling, some swearing, and I guess we backtracked a bit where I couldn’t get through.] I don’t know if I mentioned this but the first rule of the Coast Walk is ‘Don’t die.’

B: Oh, good!

J: So don’t break my rules, ok?

B: So when my field teams go out I give them all certain rules, too. ‘Be safe’ is the number one, ‘Have fun,’ and then actually because I deal with oil spills, it’s ‘Don’t eat the oil.’

J: Eew

B: Have fun, be safe, don’t eat the oil.

J: So, are you doing logistics for cleanup? Or you actually out in the field cleaning?

B: Fortunately I don’t actually clean, I deal with what they call ‘natural resource damage assessment’ so I figure out how bad, how much impact did the oil spill have on the environment. And then we come back in and restore the environment to compensate for any damage. So if an oil spill impacts pelicans, say, we have to come back in and maybe make new baby pelicans to bring the population back up to baseline.

J: So like breeding them in captivity and releasing them?

B: No, you find out what the limiting factor is; like for pelicans it’s space to breed. They breed on islands, so what you do is you build an island.

J: Oh cool!

B: And when you build that island, pelicans will come back and breed there and you get credit for the new pelicans that are born there that wouldn’t have been born otherwise.

J: You know I never thought of it as … it’s like a ledger, like accounting, inflow and outflow.

B: We count it as debit and credit.

J: That’s the words I was looking for.

B: That’s exactly what it is. And I work with economists every single day to do that accounting. So there’s a pelican debit, and we create a pelican credit, and when the two equal, we’re done.

J: So are you working on the spill in California now?

B: No, in fact I thought I was going to have to go out there but I’m not. There’s only a couple of firms that do what I do, but they happened to hire a different firm if you can believe that. So I’m not on the California spill. I do a lot of work in the Gulf. I recently had a spill out in Illinois, [and one in] North Dakota.

J: I keep thinking I should hand everyone who walks with me a 4 pound piece of glass, so I can keep up to them.

B: I thought about bringing a camera, I thought about bringing binoculars, and I’m glad I didn’t do either.

J: It’s so much easier with two hands!

B: If you want me to carry anything or need any help let me know.

J: Naw, I need to carry my own camera and the other stuff is on my back where it doesn’t matter.

B: [Looking over the edge of a deep cleft barring our way] I think this might violate your rule of dying, so maybe go up and around?

J: [Sighs] Let’s see. No good. [We climbed around the edge of it.] It smells good to wade through, though. The sweet fern. There’s the road again.

B: I know we want to avoid the road, should we head back down that way?

J: Yeah, actually, let’s do that. Lot of up and down today, huh?

B: When you have to walk back, how do you walk back? On the roads?

J: Yeah, I take the easiest route back.

B: So when you’re done with the project, what is the plan?

J: Write a book. I mean I’m writing a blog as I go, which is really helping kind of pull stuff together, but I think it’ll make a great book, the question is gonna be how do I fit it into a reasonable size book? There’s so much information.

B: It’ll take you a year, right?

J: [Laughs] More like three.

B: Three years? Oh my god Jenn, hurry up, walk!

J: Well there’s this making-a-living thing, you know?

J: I’m going to go around and see if we can get down that side. … Nope. it’s pretty sheer. But I think we can get down that. …

B: Bad day to die!

J: Is there ever a good one?

…

B: Let me know if you need a hand.

J: Thanks. I’m getting pretty good at this [climbing one-handed with the camera tucked under my left arm.] This thing on the end of the camera is technically to cut glare … but it’s most useful at keeping my camera lens from smacking against cliffs while I’m climbing. I’ve killed one filter. I keep a clear UV filter on the end of the lens, and I [scratched] one this winter which made me really glad I had it.

…

B: [Looking down at a possible route to the shore] Right here you were thinking?

J: I was hoping! No? Does it look do-able from up here?

B: Well, it would be tricky. Could we do it? Yeah we could!

J: Only if we were willing to jump 6 feet!

B: Yeah, we could get over on this way and kind of hug our way down.

J: Let’s check out the next one.

B: I’m thinking the next one is…

J: No, this one’s not looking any better

B: Well down there we could, clearly.

J: What do you think, go through the woods and see if we can get onto that slope-y bit?

B: So I went to Africa last fall.

J: Oh my gosh, where?

B: Down the Zambezi River.

J: Wow!

B: So we started, we saw Victoria Falls. Oh, we could go right here! Do you think we could do that?

J: No, cause once we got to that jumping off point, it looks like another 6 foot jump to me.

B: I think we need to continue on through here. So we started at Victoria Falls and then went whitewater rafting for three days down the Zambezi. 21 sets of rapids, 10 of them were Class V.

J: Oh my god

B: It was great. That was really amazing. Then we went down to the lower Zambezi where we spent 4 days canoeing with hippos.

J: Oh my goodness! That’s kind of dangerous, isn’t it?

B: Oh it was great fun. Yes! It is dangerous, and yes, it was great fun.

J: Just like the Class V rapids.

B: Yeah.

….

J: [We finally found a passable slope] There we go! God, all the pollen coming off of these things! Whew! [The conifers were shedding pollen like snow.]

B: Gonna be a little bit of a drop but I think we can do it.

J: I’m gonna hand you my stuff.

B: Got it. Yes, there you go, you got a good one there [foothold].

[Sounds of scrambling and plopping.]

J: Okay, I’ll take that back.

B: We’re covered in pollen!

J: Oh my god look how gorgeous that is … I’m just getting the pollen off my lens.

B: [Looking out along the shore] Beautiful, look at that. You have a good job.

J: I wish it was a job!

Rockweed covers boulders at low tide off Hunters Point, Acadia National Park, Maine

B: Okay, you’re the boss, how do we – do you go down closer to the water?

J: Let’s go down

B: So what do you do for a real job?

J: I rent my house out in the summers. And I mean I earn something from photography but definitely not a living. This year I’m going to be giving workshops over the summer, too. [And a couple months after this walk I started working as a landscape architect again, too. I’m with LARK Studio in Bar Harbor.] I think that’s a black-backed gull over there. God they’re huge, aren’t they? Now we just kind of pick our way through the seaweed. Carefully.

…

Periwinkles and several forms of coralline in a tide pool, Acadia National Park, Maine

J: Look at the colors in here. Between the striped rock and the coralline? That’s so cool.

B: Whoop! It’s a bit slippery!

J: Thanks, I appreciate the warning.

…

J: OK, I’m going to take your picture now.

B: Really?

J: Yup. Smile.

B: Ok. I don’t know about that.

J: It’s ok, I’ll [pick] the one where you’re not making a funny face and your eyes are open. Although you’ve got sunglasses on, so …

B: I always wear sunglass

J: so it doesn’t matter. I always take 4 or 5 pictures of people because I learned after the first time that someone is going to close their eyes and have their mouth half open.

B: I love these rocks. My wife used to collect rocks like this that looked like bird eggs.

J: I have so many.

B: I do too, absolutely, they’re all over.

J: People at the Park were a little concerned about my beachcombing in the Park, and they were mostly worried about rocks, and I was just like, ‘You know what, I have way too many rocks already, you don’t need to worry.’

[Wind drowned us out]

J: I’ve actually got an old CD storage thing, it looks like an old filing cabinet but the drawers are just CD-sized, it’s just filled with rocks. Because all our music is digital now.

B: I like the lucky rocks. The striped ones.

J: Yeah, and … when you think about what went into making this?

B: Yeah.

J: Like this is probably the older rock, and this is the volcano coming up through, and then … thousands of years right there just making the rock, and then time for it to fall off and weather …

B: Millions of years old.

J: It’s just kind of mind-boggling when you think about the process of making these. Which I never did before I started this walk. I was just like, ooh, striped rocks! But I’ve been learning about all kinds of stuff.

…

J: Jane Disney was out [on the Coast Walk] once. She’s waiting for me to get back around to the mudflats.

B: I’m meeting Jane today. …

J: What are you guys working on?

B: The Frenchman Bay Partnership is working on a new tool that my company’s helped develop, which is an ecosystem services [tool]

J: Oh! I was part of that! I came to the [community workshop] at Galyn’s [Restaurant]… That was a very cool thing. [About thirty members of the business community came together to discuss priorities for Frenchmans Bay – aquaculturists and seafood dealers were concerned with clean water and species populations, kayak tour guides were concerned about preserving views and public access, things like that, and Brian’s process helped sort out the concerns and prioritize them, which was a first step in developing a management plan for the bay.]

B: So we’re gonna do that again on the other side of the bay next week. And once we have more information we should be able to take it now to the next level.

J: It’ll be interesting to see if the priorities are the same on the other side.

…

B: Whoa.

J: You okay?

B: Yup. I would not recommend taking that route.

J: Would you admit it if you were not okay?

B: Yes.

J: Good, just checking.

B: I am well beyond that in my life.

J: … My first reaction after hurting myself is always, “I’m fine, I’m fine” and then, “Um, no I’m not. Maybe I need help.” I mean not right now.

B: I’ll admit, it depends on how I hurt myself.

…

A Herring Gull had caught a crab and was trying to pull its claws off when a big wave crashed nearby and startled it off its perch.

J: Whoa! Did you see that?

B: Yeah. [Laughing]

J: It didn’t drop its crab, either. Oh man, I hope I caught that. …

…

B: …On the Zambezi just below Victoria Falls there were these giant columns of that black basalt sticking up and you could tell that they were lava tubes, and the river had come and eroded all around them. And they were as big as a house, just coming straight up about 400 feet.

J: I would love to see that. I’ve just started learning about geology and it’s just – my mind is constantly getting blown. I’m surprised there’s anything left up there.

B: It’s really cool and people don’t know it, they think ‘oh it’s just a bunch of rocks,’ right?

J: Yeah, it’s just sort of there.

B: Look at the black there.

J: Oh yeah. [Looking at deep grooves in the rock.] So do you think this is glacial?

B: I do. And right here you can see … where they crossed. It blows my mind that the Georges Banks is a terminal moraine. And that that’s where the rest of our island is, is out creating the Georges Banks. And this was the Wisconsin Glacier, so it’s what covered pretty much the north half of North America.

J: Wait, this wasn’t the Laurentide? Or is that part of the same one?

B: Well, I’ve always understood it to be the Wisconsin Glacier. Now, I don’t know if this is a different lobe? If you know something different, I could be wrong.

J: I don’t know, I could be remembering wrong. Like I told you, I’m new at this!

B: There were multiple lobes to the glaciers, so this could be, what did you call it, the Laurentide?

J: Laurentide. From the St. Laurence Basin. …

B: I remember reading about the Wisconsin because that’s what we were dealing with in Illinois.

J: Oh so you come halfway across the country and you’re still in the same glacier.

B: Exactly.

[We were both right – the Laurentide Ice Sheet was one of several ice sheets included in the Wisconsin Glacial Episode. The Laurentide covered this area and melted about 20,000 years ago.]

…

[Sound of gulls and wind in the background]

J: Check out that wall. That is gorgeous. [And nobody sees it unless they come down here.] They really did amazing work, all the Park masons.

B: I like the rock in front of it, the jagged, more the basalt, small squares versus some of this granite.

J: The juxtaposition.

…

B: [looking into a tide pool.] I’m always amazed there isn’t more stuff. But I guess it’s a very difficult environment.

J: Part of it is also that we’re higher up. The lower tide pools have more diversity. But they also have thicker seaweed so it’s harder to see. Yeah, I’m just seeing a couple of blue mussels and mostly periwinkle.

B: Right.

J: Couple of limpets. Scud.

B: What’s the little swimmy things?

J: Probably scud. Wow, it’s almost getting warm enough to start walking in the tide pools. I think come summer I might start hiking in my scuba boots.

B: Oh, yeah.

J: So I can just walk in through them.

B: How are they on the sole, though. Do they have a hard enough sole?

J: They wouldn’t be great. The barnacles would destroy them after a few hikes.

B: Well my thing is I don’t want to feel the rocks under my feet.

J: Yeah.

B: You don’t want to go hiking in tennis shoes

J: Yeah, that’s why I’ve got these. Well, I think it’ll depend on the terrain I’m going through.

…

J: Hard to see anything from up here.

B: There doesn’t look to be a lot in here. I see a couple of periwinkles, I don’t see any mussels at all.

J: I’m looking over where the kelp is, and I can see there’s a lot more coralline growing over there and what with the big kelp it looks more promising, but there’s no way I’m getting over there. [Laughs] Turning around [is tricky,] it’s like a 12-point turn.

B: Yeah, careful.

J: It’s actually harder now than it was in the winter.

B: Oh really?

J: Yeah, cause in the winter I had creepers.

B: Right.

…

J: I have got to get actual hiking boots. [I was wearing my winter snowboots.]

B: I’m not sure what boots would be good on this terrain.

J: Well, these are just a little bit sweaty. Non-insulated hiking boots would be an improvement. But mine literally fell apart – the soles of both of them came off.

B: Saltwater’s not good for them.

J: Yeah. Well they were also 20 years old.

B: Oh that would do it. Sounds like a trip to Cadillac [Mountain Sports] is in order.

J: I just haven’t made the time so I’ve been hiking in snowboots.

B: I’m sure you’ll do that more gracefully than I just did.

J: No, probably not. … Yeah, definitely not.

B: This is incredible. This is really really pretty.

J: And we are not getting down to it.

B: I want to get down into it.

J: There’s no way. Unless there’s a … no.

B: And if we got down into it there’s no way to get back up either.

J: Well getting up’s always easier, but no. …. I think we’re just going to have to look at this one. … Wow.

…

J: [sounds of plastic clattering against stone] Ow. I’m okay. My camera’s okay.

B: I almost brought my backpack with the first aid kit.

J: I have a little first aid kit. Bandages and alcohol wipes, mostly.

B: I figure alcohol is for after.

J: Yeah, we’ve earned a drink.

B: I can keep going on up here, probably easier than going around.

J: Okay.

B: You okay?

J: Yup.

B: Nothing broken?

J: Scraped, but not broken.

B: Scrapes heal.

J: Exactly.

B: You know what, we probably should head up to the road.

J: I think you’re right. Save a little wear and tear on ourselves. ….

…

B: I hate taking you away from the water.

J: [Starting to sound pretty tired] It’s okay, it’s still shore. Close enough. Don’t put your hand in the deer poo there.

B: Oh, thank you. How about you.

J: I missed it, thank goodness. [Looking at a crab shell.] See we’re still on the shore, there’s marine life up here.

B: Thanks to the seagulls.

…

B: Should we go down?

J: Um, if you don’t mind, let’s walk up here a little bit, I’m kind of needing the rest. …Walking along a level surface is a rest!

B: I don’t mind. If this is all good with you?

J: This is all good with me. The point of the project is to understand how the different parts of the island all fit together and how one kind of landscape turns into another. I feel like I’ve got a pretty good sense of this shore now, and it still looks pretty much like what we were climbing over. If there was a big change, I’d be like, ‘Oh, we gotta go down,’ but …

B: Yeah I was thinking we could’ve gone down there but then we be stuck [climbing up this.]

J: Yeah, but you know, that’s what this whole thing has been like. You go down, you go as far as you can, and at some point it drives you back up. .. But when I start slipping and drawing blood then it’s time for a rest. That’s where I really need new boots. Because these, my foot slides around inside. Gotta get my butt down to Cadillac.

B: Maybe if you agreed to put a Cadillac sticker on your backpack they’ll give you boots.

J: Oh heck, I’d wear a Cadillac flag if they’d give me boots. Wouldn’t that be sight to see!

B: We’d know where you were.

J: Put a bumper sticker [slaps a particular body part] right there.

B: Back in Illinois [there’s] tall grass prairie and I went hunting for the first time and the question is [when] the grass is taller than the people, how do you figure out where the hunters are? So what we did is we’d take bike flags and [inaudible] this is your spot. Turns out that they didn’t really like that spot, so they ended up carrying the bike flag with them as they walked around, and we could stand up on an observation tower and watch all these bike flags moving around.

J: That’s hysterical! Wait, are we there?

B: This is Little Hunters

J: Let’s go down! I can handle stairs.

B: I’ve never been down here. Little Hunters Beach.

J: I haven’t been down here in a long time. My kids were toddlers.

B: Oh this is perfect. If only there were stairs on the way back up! Or maybe we’ll come back up.

J: Well, if we get to Hunter’s Beach, there’s the path. Not if, when we get to Hunters Beach.

B: That is the problem with having the car there.

J: Yeah, exactly, we will get to Hunters Beach! And we’re practically there, it’s just around the point.

…

B: God, I need to get out hiking more. So we had a friend visiting, he’s younger, visiting with his girlfriend, he asked us where to go hiking and we rattled off our favorite hiking spots. He pointed out that they’re all less than two miles in to the ocean. Hunters Beach, and Ship Harbor, things like that. Yeah, that’s where we hike. Less than two miles to the ocean.

J: And why not? I mean, what more could you want in a hike?

B: He was crazy, he hiked mountains and things!

J: Oh I did that. I had a friend, she moved away, but while she was here she wanted to climb every mountain on the island. So there was one summer where she would just be like, ‘Ok, I’m coming to get you,’ and she’d come drag me out and we’d climb a mountain.

B: Well that’s a goal we had for a while, hiking every mountain. And we hiked a lot of them.

J: But not all?

B: Nah. Why would I hike Cadillac, I can drive up it?

J: I’ve heard that the North Ridge is pretty cool.

B: I understand, but you still hike all the way to get to the top and go

J: Yeah, … tour buses. No, I kind of agree with you, I’ve never hiked it. But then I don’t usually do mountains any more. [because all my spare time goes to the Coast Walk] We used to try and haul the kids up when they were too little to argue.

B: Oh, we did it when they were old enough to argue, and then we got tired of listening to them.

J: Yeah. That’s pretty much… when they were probably about ten it started to be more trouble than it was worth. Because up until then we could lure them onward with M&Ms. Then once they got to be about ten or eleven it didn’t work so well.

J: OK, there’s something swimming in this pool. What is that? … Where’d it go? … Well, gone now.

B: Saw it. Oh, there’s a water strider.

J: Oh, mosquito larvae. There’s something there. Some kind of larva. It doesn’t look like a tadpole-y sort of thing. It’s so depressing seeing mosquito larva. Oh, there’s a whole bunch of these little black things swimming around.

B: I just saw that little one over there.

J: Let’s see what happens if we move a big rock.

B: What’s underneath that rock? Critters?

J: Looks like the cast-off skins of something. [Loud splash.] Ah! Sorry. Slippery.

B: That’s not a worm is it? Oh, that’s seaweed right there.

J: A waterstrider. Oh, a couple of them.

B: Yeah, I’ve been watching, there’s one there.

J: I wonder what these white things are. It looks like something used to be attached, doesn’t it?

B: Mmhm. Are they slimy? Is is a snail trail? There was something attached!

J: I got one! It’s a shrimpy kind of thing.

B: Oh cool.

J: Looks more like a shrimp than like a scud. But what on earth is it doing all the way up here?

B: Quick hands! To catch that.

J: That was fun. It’s like being a kid. Catching things in tide pools.

[Another deep cleft – shatter zone – the Cadillac Mountain granite intruded into the older rock – BH Formation/Series and diorite]

B: Oh boy I think we’re

J: going around?

B: unless you feel like jumping!

J: Yeah, no. Wow. Oh, this is amazing. … didn’t I just say, ‘ oh it’s just around the bend?’

B: But I agreed with you. It is just around the bend, we didn’t know about this!

J: We didn’t know how many bends there were around the bend.

B: I want to go that way but I think we’re better off going this way.

J: Yeah, that looks painful.

B: And it looks like something has gone here.

J: Well there’s deer hoofprints.

B: oh dear!

J: Hmm?

B: Bad joke

J: Ha!

I think this might be the cleft I found in these photos:

“Raven’s nest” Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Acadia National Park, catalog #ACAD29539

A little background on the photos – I came across these in a box of unidentified, apparently random photos in the park archives. Certain photos are labeled “Flying Squadron Mountain,” which gives us a good idea of when they were taken. [Flying Squadron was called “Dry Mountain” on early maps, renamed “FS” around 1918, and re-renamed “Dorr Mountain” after Dorr’s death in 1944, so the photos are from the ’20s or ’30s.] The box was full of photos of wildlife, with labels like “Kildeer Eggs in Nest.” This particular sequence started with the raven chicks above, then

“Sully photographing the ravens nest” Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Acadia National Park, catalog #ACAD29539

showed the photographer perched on one side of the cleft (at right) looking down at the ravens’ nest (lower left.) The photographer is identified as “Sullivan” on other photos, so I’m guessing “Sully” is a nickname. Then it starts to get really good:

Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Acadia National Park; ACAD29539 Box 44 #1317

Apparently they wanted to band the raven chicks, so there are 2 guys on top of the cliff with a rope, lowering a third guy down the cliff face. Can you see him there? The nest is directly below him, near the middle of the photo. In the photo below he is dangling with his toes barely on a crack in the rock.

Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Acadia National Park; ACAD29539 Box 44 #1322

And now he seems to be sitting on the nest:

Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Acadia National Park; ACAD29539 Box 44 #1320

The look on his face is very expressive, isn’t it? “If you drop me I will haunt you.”

“Banding Ravens” Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Acadia National Park, catalog #ACAD29539

B: [inaudible, something like Hunters Beach is one of my favorite hikes.]

J: Now why is that? Not that I don’t agree with you, I’m just curious.

B: I love the trail going down there. I love that you start walking down, you can hear the creek going as you’re walking on the path, and then you see the creek, and then as you’re walking down and then you hear the waves crashing

J: And the rocks

B: and the rocks, they’re moving, ch-ch-ch-ch. You hear it before you see it and then when you see it it’s absolutely amazing. And I love doing it in the wintertime because I love that creek in the wintertime when it’s all kind of frozen … I come here a lot because I live down the road; a lot of times for work, like at lunchtime if I want to take a break from what I’m working on, I’ll quickly come do this walk, get rejuvenated.

J: You know the kind of beaches that I go to when I’m beachcombing are completely different. I mean, this one’s not even on my list for beachcombing because [the things you find you aren’t supposed to take out of the Park.] Hulls Cove is an ideal beachcombing beach.

B: But this one, to me it’s the sound. It’s all of the senses.

J: No, I agree with you, I love both this one and Little Hunters Beach.

B: I had never been to Little Hunters before. You gave me a new area.

…

J: I’m glad we’re doing it this time of year, these raspberries would be a real pain.

… [halfway down the rocks at Hunters Beach]

[And then my recording stopped abruptly! No idea why.] We went straight down that cliff in the photo above, and then sort of diagonally across its face to Hunters Beach. It was geology up-close-and-personal!

We’re back in the shatter zone again, and there were some pretty good sized quartz intrusions.

You can see the pink granite intrusions pretty clearly against the older (dark) diorite in the background above. And there’s Hunters Beach, so close and yet so many steep drops away…

This was the final scramble to sea level – you can see a thick band of barnacles just above the water:

In the middle of scrambling down that pink granite spire I spotted this Sphinx Moth caterpillar, and had a quick session of Photographer’s Yoga trying to photograph it (many thanks to Anne Swann for identifying it!):

And then suddenly we were safe on Hunters Beach, listening to the stones rattle in the waves.

I looked back up at the rocks we’d just climbed in equal parts disbelief and pride. I had no idea I could do that! (Thank you, Brian!)

In the next episode Tim Garrity of the MDI Historical Society and Lynn Boulger of the College of the Atlantic join me in wondering why hundreds of starfish are peeling off the rocks at the other side of Hunters Beach.

Pingback: Coast Walk update – Jennifer Steen Booher, Quercus Design

Amazing photographs from the Archives of Acadia and an incredible story of walking on all those rocks to have the experience and the photographs of more recent times. Thank you.

So much information here!! There’s something for the historian, the geologist, the marine ecologist. Please write the book! Also please email me the info found on the campgrounds found and photos? Email address below. What a wonderful project this is and following with much interest.

Hunters is a favorite of mine too. This article is wonderful. I do hope you are writing the book. I miss Brian! I drive by his house every day. The daffodils are up, making me remember Patti. I worked with their daughter, Noelle, for 3 years.

Thank you Sydney, I’m glad you enjoyed it!