April 20: 34 degrees, sunny, 49º by the time I finished. Not warm, but pleasant.

Suddenly I’m surrounded by wildlife: 2 Downy Woodpeckers (Picoides pubescens), 1 Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus), a white-tailed deer, a raccoon, 4 male Common Eider and 3 or 4 females (Somateria mollissima), a flock of 12 Black Guillemots (Cepphus grylle), then a second flock of about 15 (flying, so hard to tell), 2 Black-backed Gulls (Larus marinus), several song sparrows (Melospiza melodia), 1 crow, 1 cormorant, 1 loon.

This past week I’ve trekked from the northern side of Schooner Head to the northern edge of Great Head, and it was fascinating and exhausting, and there was so much to share I had to break up the journey into three posts before it turned into a book. I mean, I hope it will be a book, eventually, but right now it has to be short enough to load! So this is the first post.

As soon as I walked onto Schooner Head, I had left the park and was on private property. I had permission from most of the landowners, but as you can see in the map, not from all. If anyone is reading this who did welcome me, Thank You So Much! The terrain at the shore was steep clefts in the rock, covered in slippery moss-like green algae, and for much of this portion I tucked my camera into my backpack and clung to the stone with both hands while inching along the ledges. It doesn’t look all that high, but it felt like I was climbing Everest. Unfortunately, that meant I didn’t get a lot of photos here.

The rocks I was scrambling over were very cool, and I wish I knew more about them. I do know that the middle one is called a dike, and that dark seam is diorite that came up in liquid form through a crack in the older stone, which I think is part of the Bar Harbor Formation:

I didn’t spot a lot of wildlife down there, but I did find an unfamiliar snail, which after research I think is a Northern Lacuna (Lacuna vincta.)

Over the course of the day I spotted a surprising number of birds, given how empty the ocean has felt most days so far. Clockwise from top left; eider duck, loon, black backed gulls, a flock of guillemots, and a downy woodpecker:

Eventually there was (as usual) a wall of rock straight into the ocean, so I backtracked and scrambled up to the top of the cliff. It stayed high and steep, and I wasn’t able to get back down to the shore within the property I had permission to visit. This is looking down into one of the rock clefts from the cliff top.

Up on top of the cliff, a pileated woodpecker took one look at me and fled. (You’ll see this is a bit of a theme this week.)

Up on top of the cliff, a pileated woodpecker took one look at me and fled. (You’ll see this is a bit of a theme this week.)

When I reached the property edge, I headed back to the road and visited the next place for which I had permission, on the south side of the Head. There are a few items of interest in the middle section which I didn’t get to scout out, but I can share old photos of them with you. There were cannons placed here during the Civil War Spanish-American War [see note at end of post] and although they are long gone now I’ve heard the foundations are still there.

Schooner Head used to be a tourist destination because of the Spouting Horn, a phenomenon somewhat like Thunder Hole: “Schooner Head is a bold headland on the coast, with high rocky cliffs, breasting the surf. In one of these is a long, tunnel-like opening, from whose inner end a cleft opens away into the top of the Head. During rough water the waves rush madly into this passage and dash out at the top, throwing showers of white spray many feet into the air. This is the famous Spouting Horn, which, on the pleasant days usually chosen for this excursion, forbears to spout. Venturesome persons have climbed up through the Horn, at low tide, but it is a perilous and uncomfortable journey.” [excerpted from ‘Sightseeing at Schooner Head,’ M.F.Sweetser, 1888 (as reprinted in Discovering Old Bar Harbor and Acadia National Park, Ruth Ann Hill, 1993.)]

“There are various wild legends connected with the white stain on the seaward face of the Head, which bears a singular resemblance to the lower sails of a schooner. One of these tells of a pirate-schooner, one of Capt. Kidd’s, running in to make a harbor and land treasure at Otter Cove, and disabled off this shore by a broadside from a British corvette, after which she was dashed to pieces on the Head. Hence the mariners along the coast, a century or more ago, often fancied they saw, off this point, the ghost of a schooner, with a shadowy helmsman, flitting past in the white moonlight. There is also a tradition that one of His Majesty’s cruisers ran in here, during the War of 1812, and opened up brisk fire upon the cliff, under the impression that its white face, dimly descried through the fog, was the mainsail of a flying Yankee schooner.” [another bit from ‘Sightseeing at Schooner Head’]

There’s also a small cemetery, and according to Cemeteries of Cranberry Isles and the Towns of Mount Desert Island (Thomas F. Vining, 2000. Updates are posted on this page of the MDI Historical Society’s website) it is occupied by Albys, Bauers, Clarks, Lynams, and Vaughans. I couldn’t see it very well even with a telephoto lens:

The south side of the Head continued the predominantly Red Oak forest we’ve been walking through since High Seas, although I found some White Oak leaves, and there were several stands of Paper Birch and (possibly) Yellow Birch.

The view toward Schooner Head, about 1895. The Brigham cottage stands in the open. “The small creek that flows into the cove … powered a small seasonal mill. The summer cottagers got their water through an aqueduct from the Bowl… . The 1947 fire was traveling at maximum speed and intensity when it passed through here. It burned everything in its path, including the cottages on the Head and nearby (except High Seas).” (photo from Discovering Old Bar Harbor and Acadia National Park, Ruth Ann Hill, 1993.)

After the rugged climbing I’d done on the north side, I was relieved to see the south side was much easier walking:

After the rugged climbing I’d done on the north side, I was relieved to see the south side was much easier walking:

It was comparatively flat with only small patches of slippery algae, and honeycombed with the best tidepools! (Please remember this is private property and don’t make the kind people who gave me permission to show this to you regret their generosity.) Why were they the best? Because they were gardens of seaweed. Seriously, I have never seen so many species flourishing so thickly.

I think I’ve mentioned before that seaweeds stump me, and most of these are new to me, but I managed to identify a lot of them. The wide, flat leaves are a Laminaria species, the wide, frilly leaf with a bright central stem is an Alaria species, the squiggly brown ones are Dumontia, and some of the bright green is Sea Lettuce (Ulva lactuca). I don’t know what the other bright greens are. Yet. The yellowish one at bottom right is Knotted Wrack (Ascophyllum nodosum).

This bright green stuff is Enteromorpha:

The brown patches that look like lichen are a crustose seaweed, meaning it’s a plant that grows as a crust on the stone, maybe a Ralfsia,

while this reddish coloring is probably a different one, probably Hildenbrandia:

while this reddish coloring is probably a different one, probably Hildenbrandia:

So many new species, and I’m only a couple of miles from home! I wonder if it’s because the shorelines I usually beachcomb have a gentler slope, and the ones I’m on now are rock outcrops with a steep drop-off, so I’m seeing species that prefer deeper water or less exposure to the air? Maybe if I’d been able to reach the shore along Sols Cliff I would have seen these sooner?

Now this is something cool that I just learned here – see all the paler dots on the strands of Fucus in the photo below?

Those are conceptacles, the reproductive organs of the plant. They release male and female gametes into the water, and the resulting embryos attach themselves to the rock to form new plants.

I was so busy staring into the tidepools and trying to get photos of all the different seaweeds, that I didn’t notice I had company. At some point I looked up, and a raccoon was standing about five feet away with a shocked look on her face. I kid you not, if she could have spoken, she would have said, “Get off my rock!” She took off as soon as I noticed her, and I only got a few fuzzy photos of her fuzzy bottom.

The ledges with the amazing tidepools eventually sank down into a cobble beach, and I was able to do a little beachcombing there.

A little stream empties into the cove, and a small flock of song sparrows was splashing around in it. They took off when they saw me, but several of them came back to the beach and hopped around pecking at things in the seaweed.

A little stream empties into the cove, and a small flock of song sparrows was splashing around in it. They took off when they saw me, but several of them came back to the beach and hopped around pecking at things in the seaweed.

I had left my collecting bag in the car (doh) so I had one hand full of camera and the other hand full of stuff. It looks like a bouquet, doesn’t it?

To be continued…

____________________________

ADDENDA

April 30, 2015

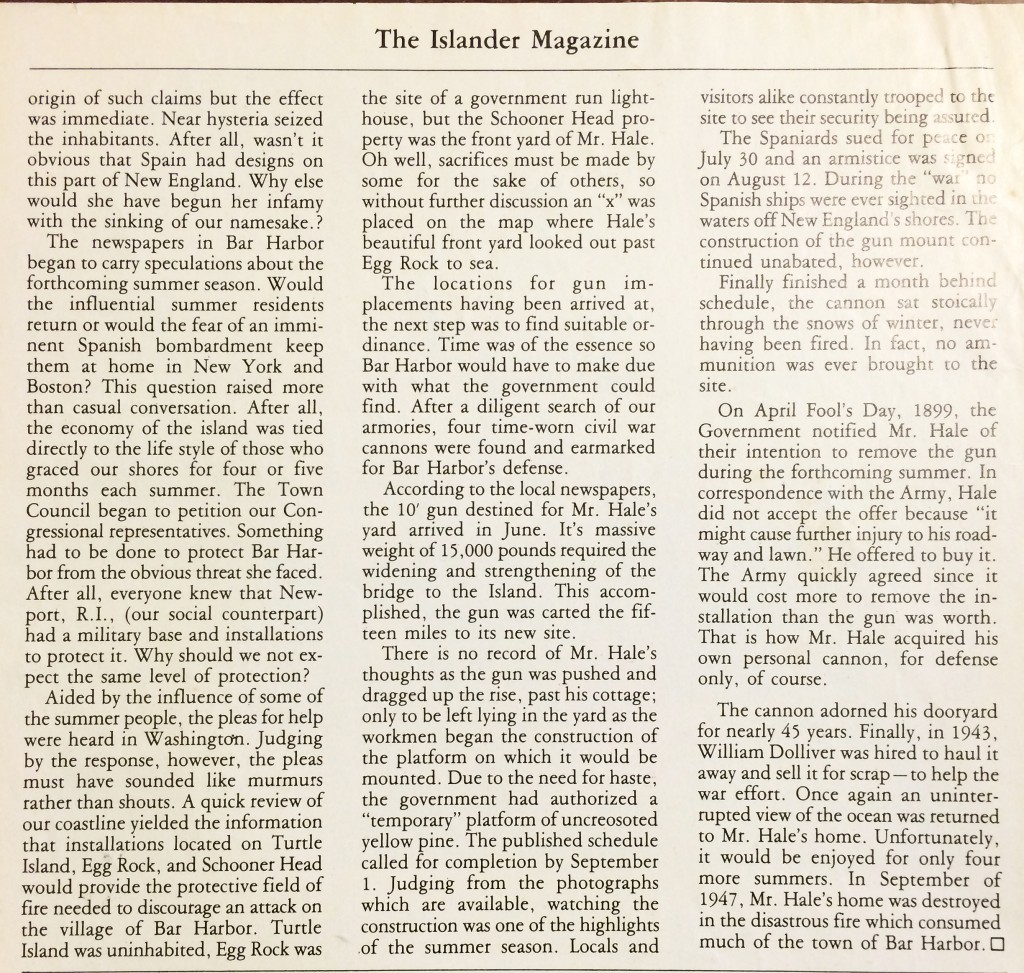

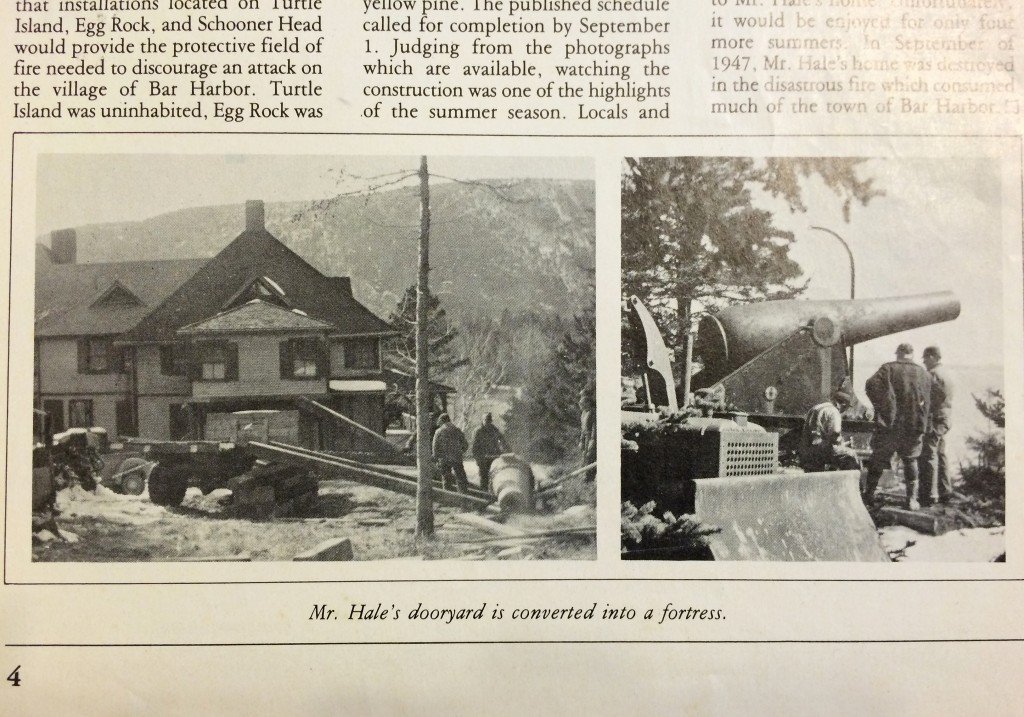

While poking around in the vertical files of the Jesup Memorial Library I came across an article about the cannon (“Cannon in the Dooryard,” Frank Matter, The Islander Magazine, date unknown) that filled in a lot of the details. It was apparently placed on Schooner Head, in the front lawn of the Hale estate, in June of 1898 following the sinking of the battleship Maine in Havana harbor. Because the country expected to be attacked at any moment, the government scrounged up four old Civil War-era cannons and sent them down east. The other guns were placed on Egg Rock and Turtle Island. The bridge to the island had to be widened and strengthened to bear the weight of the cannon. It was a short war – the armistice was signed by mid-August – but the gun emplacements were not completed until October. They were, obviously, never used. One can only imagine how irritated the Hales must have been to have construction going on through the entire summer season. According to the article, Mr. Hale refused Washington’s offer to remove the cannon, saying , “it might cause further injury to his roadway and lawn,” and the cannon remained in the Hale family’s front yard until 1943, when it was sold for scrap as part of the war effort. The Hale estate was destroyed in the Fire of 47. I’ve included the full text of the article for your amusement:

May 5, 2015

Found a couple of photos of the Hale estate before the fire:

and after:

The caption reads, “His Schooner Head estate in ruins Richard Hale pluckily starts a new chapter of his ‘The Story of Bar Harbor,’ a scholar’s must.” From “Mount Desert The Most Beautiful Island in the World” by Sargent Collier and Tom Horgan

November 6, 2016

from “Opulence to Ashes: Bar Harbor’s Gilded Century” by Lydia Vandenbergh

The first European settlers on Schooner Head were William Lynam and Hannah Tracy. Married in Gouldsboro, they moved to MDI in 1831 and started a hundred-acre farm on Schooner Head. [As a side note, can I say how much it irritates me when history books say that male settlers came to the island and brought their wives with them? I don’t think any pioneer farm survived unless it was a joint enterprise, so can we please just start saying ‘they’ instead of ‘he?’] There were few inns on the island until later in the 19th century, and the earliest tourists often boarded with local families, including the Lynams. Several of the early artists who visited (including Frederic Church, I think) stayed here.

Outbuildings of the Lynam farm, with a fish oil press in the foreground. Photo from “Opulence to Ashes: Bar Harbor’s Gilded Century” by Lydia Vandenbergh.

Sawmill on the Lynam farm. Photo from “Opulence to Ashes: Bar Harbor’s Gilded Century” by Lydia Vandenbergh

‘Schooner Head and Lynam Farm,’ Frederic E. Church, 1850-51. From “The Artist’s Mount Desert” by John Wilmerding

Charles Tracy, a New York lawyer and one of the earliest tourists to MDI, kept a diary of his visit here in 1855. Here are his descriptions of Schooner Head and the Lynam family:

from “The Tracy Log Book 1855” edited by Anne Mazlish

from “The Tracy Log Book 1855” edited by Anne Mazlish

You may already know some of this, but a whole web of connections spreads out from that 1855 visit. Charles Tracy’s daughter Fanny, who traveled with him, later married J.P.Morgan. She brought him to Mount Desert Island for their honeymoon, they built a house here, and most of the senior members of his firm (the ‘Morgan Men’) started summering here and building houses. The Morgans bought Great Head for their daughter, Louisa Satterlee (see Coast Walk 8) – her children donated it to the National Park. Alessandro Fabbri, whose WWI transatlantic radio station we talked about in Otter Creek, was the son of one of those Morgan Men. So the web goes from brown bread at the Lynam farmhouse to Gilded Age cottages along West Street to submarines in Otter Cove. Crazy, isn’t it, what one tourist started?

________________________________

WORKS CITED

Collier, Sargent and Horgan, Tom, Mount Desert The Most Beautiful Island in the World.

Helfrich and O’Neil, Lost Bar Harbor.

Hill, Ruth Ann, Discovering Old Bar Harbor and Acadia National Park, 1993.

Matter, Frank, “Cannon in the Dooryard,” The Islander Magazine, date unknown.

Mazlish, Anne, ed., The Tracy Log Book 1855: A Month in Summer, Acadia Publishing Co., 1997.

Sweetser, M.F., ‘Sightseeing at Schooner Head,’ 1888 (as reprinted in Discovering Old Bar Harbor and Acadia National Park, Ruth Ann Hill, 1993.)

Vining, Thomas F., Cemeteries of Cranberry Isles and the Towns of Mount Desert Island, 2000. (Updates are posted on this page of the MDI Historical Society’s website)

Vandenbergh, Lydia, Opulence to Ashes: Bar Harbor’s Gilded Century, Downeast Books, 2009.

Wilmerding, John, The Artist’s Mount Desert, Princeton University Press, 1995.

Save

Pingback: Coast Walk 7 still life | The Coast Walk Project