Prologue: for folks who haven’t seen the Coast Walk lately, I received a Kindling Fund grant this year to help with the cost of transcribing interviews. Usually I talk to people while we are hiking a section of coast, but I need to use up my grant by the end of the year, so just for this fall I’m interviewing people wherever and whenever they are willing to meet. I’ll present the interviews to you as they happen, and tie them back into the Coast Walks when I pick up that thread again.

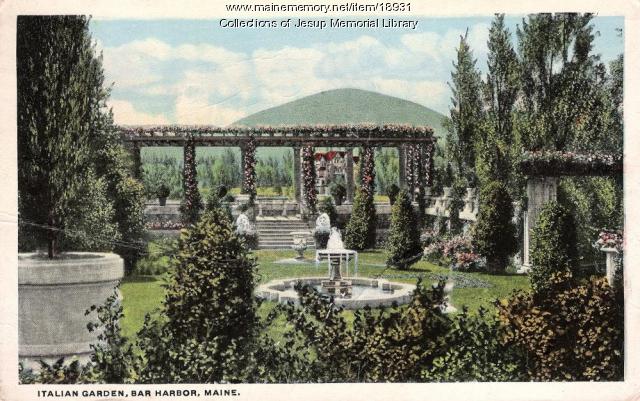

The view from the Asticou Inn.

On October 3, 2017, on a cold, sunny morning (40ºF), I sat down to breakfast with Earl Brechlin at the Asticou Inn. Earl was, until this fall, the editor of the Mount Desert Islander (and the Bar Harbor Times before that), so there’s not much happening on the island that he hasn’t heard about. He’s also a Maine Guide, a historian, a collector of antique postcards, the author of several books about Maine, and as of September, the Communications Director for Friends of Acadia.

Jenn: Thanks for meeting with me. I have to admit I’m really nervous about interviewing you.

Earl: Really?

Jenn: You’re an actual journalist.

Earl: [Former journalist] now that I left [the Islander] for Friends of Acadia. As a journalist I always get nervous when I’m interviewed because I know how many ways it can go wrong.

Jenn: Well good, maybe you’ll take pity on me then if I start going wrong!

Earl: Well no, actually you’re one person I was comfortable talking with so I didn’t worry about that.

Jenn: Phew! Let’s see, I guess the first thing is how did you end up on the island? You’re from Connecticut originally?

Gorgeous wallpaper in the Asticou dining room.

Earl: I met friends in college who had always come here and who had worked here summers and so I decided to try it out one summer. I came down and I worked as a bartender in a restaurant – bartender and waiter – and I just fell in love with the place.

Jenn: Yeah.

Earl: I went back to school in the fall up at the University of Maine, Orono, and said ‘how can I structure my financial aid and my classes to just get done next Spring and move to Bar Harbor?’ I wanted to live there, I didn’t care what I did for a living. I studied forestry and resource business management and I just decided that … that’s where I wanted to spend my life. And it wasn’t until about 10 years after that I realized that I had family ties from here.

Jenn: Really?

Earl: My mom spent her summers on Swan’s Island and my grandfather, her father, is first cousin to Ruth Moore, the writer. … Esther Trask and people over in Bass Harbor are relatives [but] it wasn’t until after I moved here that I found that all out … . My grandfather used to pull traps by hand on a Friendship sloop with his grandfather out of Swan’s Island.

Earl’s grandfather, Carl Foster, on his own lobsterboat. Carl fished out of Muscongus and Round Pond in Midcoast Maine.

Earl: I went to do a story on the Ruth Moore dig out on Gott’s Island for the newspaper and Esther Trask was my grandfather’s first cousin … . She came along and as we were leaving the island she pointed to a house up on the hill on Gott’s Island and she said that was her grandfather’s house. And then I got a chill because I realized that was my grandfather’s grandfather’s house. … And then on my dad’s side, the family [is] Burgess out of Belfast – Abby Burgess from Matinicus Light was actually a relative.

Jenn: No kidding?

Earl: So I had a lot of ties in Maine that I didn’t even realize.

Jenn: So it’s kind of kismet that you ended up here.

Earl: Yeah I think so. I think people end up where they want to be, I mean how did you end up here?

Jenn: Let’s see, so Brian and I started dating in college, and we moved out to California together and loved it. We were in San Francisco for four years. … I [was] volunteering at Strybing Arboretum [and the people I worked with] kind of steered me into landscape architecture.

Earl: Nice.

Jenn: Yeah, and so Brian had, like, every computer geek’s dream job – he was at Ziff Davis Labs back when they did all the testing for all the computer magazines. Something got invented and they put it through its paces. … And the deal was he would leave Ziff Davis so that I could go to grad school, if we moved to Maine afterwards.

Earl: That’s a fair trade.

Jenn: Well at the time I was kind of like, … I loved visiting, but I was not really sure what I was going to do in Maine [to earn a living.]

Earl: Yeah.

Jenn: And so we had a friendly competition, we would move wherever in Maine the first one of us got a job.

Earl: Okay.

Jenn: And he won, he got a job at the [Jackson] Lab, so we came back here. And you know, I’ve never looked back.

Earl: Yeah.

Jenn: … I grew up in a small town, so it’s not that different. But I had been so ready to get the hell out of that small town, I couldn’t imagine moving back to one. I loved living in Boston and San Francisco.

Earl: I bet, how nice. And so you feel like you belong here?

Jenn: Yeah. I’ve lived here longer than anywhere I’ve lived, even the place I grew up.

Earl: … I’ve had conversations with Jock Williams, who builds boats, and we’ve talked about ‘how did you end up on the island,’ and he said ‘I came here because this is where you came to build damn good boats.’ And so we would talk about that difference between finding a place you love and making a life, or going someplace to do what you love and making a life. And so it’s same destination, just different pathways to get there.

Jenn: And I’m at a point where I’m doing what I need to do to live here. I figure out ways to earn a living.

Earl: But you’re an artist too.

Jenn: Mm-hmm. Unfortunately I don’t earn a living doing that.

Earl: No, most artists don’t. Most writers don’t make a living writing.

Jenn: Yeah that’s what the weekly rentals are for.

Earl: Yeah exactly. … a few years after Roxie and I got married and built the house we have now, we built a cottage there which our family uses and we rent out by the week. And that money goes into that account and that’s what the tax check gets written out of.

…

Jenn: So what did you do when you first moved here? Did you go straight into newspapers?

Earl: No, I worked for the Colket family as one of their gardeners.

Jenn: Oh no kidding!

Earl: I had come down here and the first job I got was to be a breakfast cook at the Golden Anchor. I knew that was only part time, I needed something year-round and I heard about this caretaking gig at Kenarden so I went down and talked to them and that was year round, full time, so I went back and quit before I started at the Golden Anchor. I worked for the Colkets for almost three years with the head gardener, Harold Hayes, who grew up here and had worked for three generations of that family. And so I learned a lot of history … .

Earl: And Harold was pretty good, he said, ‘You don’t want to be the head caretaker here or anything like that so what are you doing with your life?’ I thought, ‘Well that’s a good point.’ And the Bar Harbor Times had an opening in the print shop – in Connecticut you always took printing, drafting, wood shop, metal work, as part of your junior high school training just to see if you had an aptitude for it or an interest in it … . We had a little letterpress in our basement because the company that made all these presses and type and everything … was based in Meriden, and we knew this family. We printed business cards, menus for pizza restaurants, we did all that kind of, little side hustle thing. And so I went in, I showed [the print shop] I knew how to handset type, …so I got a job in the print shop running the letterpress.

Jenn: Wow.

Earl: I said to myself, ‘You know, I could do this the rest of my life, it’s good productive work and [there’s] a sense of accomplishment.’ As a matter of fact, I used to print Caspar Weinberger’s party invitations. … He was always worried about hippies invading his parties, this is back in the 70’s, and so what he would do is for parties in California, he’d have the invitations printed in Maine and for parties in Maine he’d have the invitations printed in California, figuring nobody would leak any of them.

Jenn: Right.

Earl: But I had a camera – I was always interested in photography – so I was taking some pictures, and then they started to use [my photos] in the newspaper, and they started having me take pictures for the paper, and then I started doing the editorial dark room for the paper and … making all the prints, much to the print shop manager’s chagrin. Then there was a reporter opening and I didn’t apply because I’d flunked every English course I ever took.

Jenn: Really?!

Earl: Pretty much. Not every one, but I just really didn’t care. And so I didn’t apply because I didn’t think they would ever consider me. And the man who owned the paper at that time, Dick Saltonstall …, he came down to the darkroom and he said, ‘You know, I think you’d make a damn good reporter, I’m going to put you on the editorial staff.’ And that launched a 37-year career in newspapers. So that worked out.

Jenn: It must’ve been a good feeling, but it must’ve been a little bit terrifying too.

Earl: Oh it was. The first day, or the night before the first day, I was like, ‘What do you find to write about every week?’ And I was intimidated by that, but I hit the ground running and from that first day I never wrote all the stories I wanted to, there were just so many great stories out there.

Jenn: Yeah.

Earl: When we started out, we were using typewriters, and ‘cut and paste’ was literally cut and paste – you cut your stories apart and moved the paragraphs around, stapled them together and sent them down to typesetting. And then paste columns of copy onto pages to make the newspaper. So a lot of technology changes since then.

Jenn: It’s funny, I remember when I was in high school we had to take typing classes, everybody, guys, girls, sophomore year thing. …

Earl: Yeah.

Jenn: And of course, by the time I graduated college, we were all using Mac SE’s. Do you remember those?

Earl: I do. I remember TRS-80s, too. My father insisted I take typing. … And back then there were only people on the business track or the secretarial track and I was in a class of 35 kids, big rows of typewriters, and I was one of only three boys, it was all girls in there learning typing. And I was in the way back and I had a Royal 550 Selectric, beautiful electric typewriter, only one row of electrics. And then I got goofing around too much and for the final exam, the teacher made me move to the front row because I was fooling around with the girls in the back too much, so I ended up having to take my final on a manual.

Jenn: Oh God.

Earl: So it dropped me a letter grade but … Yeah and I always thought that was crazy, my father he insisted I do that and then I didn’t use it for years but it all came right back.

Jenn: Yeah. It’s a useful skill. I can still mostly type without looking, which comes in handy.

Earl: Well it was liberating to compose at the typewriter, and try to compose your story so that you didn’t have to cut it all apart. I remember when we first got the first typewriters where you could just back space and the white out would cover it.

Jenn: Yes!

Earl: And still, to this day, when I decide to change a sentence I backspace to erase it rather than highlight and erase. … Once we got computers and you could move entire blocks of type, that was a liberating experience too. Because you’d be typing along and you’d get a thought that you wanted for the next part of the story and maybe it didn’t go there but you got it out of your head, … you didn’t lose anything ….

…

Jenn: You never know where your life is going to take you, do you?

Earl: No Bar Harbor has been great, I had a great career in newspapers, I’m working at a great organization now, and I got married and built a couple homes and had some side businesses, and get to hike whenever you want right out the door.

Jenn: You know what drives me crazy though, is finding the time to go hiking. I live in the middle of one of the most beautiful places on earth and I don’t have time.

Earl: Well I have … debates with friends that work in Washington, DC; they come here and they get to spend a month on vacation. So do they spend more quality time here being a month on vacation versus living here year round, when you have to work so much and so hard to make it work here. It’s not an easy place to live climate-wise, it’s not an easy place to live economic-wise.

Jenn: No.

Earl: So which is the better method? I don’t know, like driving over here today and seeing the ponds and looking out this morning at the frost and everything else, those are all intangibles that you’re not going to get living 11 months in Washington.

Jenn: Well I made my choice.

Earl: Yeah.

…

Earl: I think when I look at being in the newspaper business, as you well know, the best stories never made it into the newspaper.

Jenn: I’m sure.

Earl: Or the juiciest stories never made it into the newspaper. But at the same time, we dealt with people on their best days and then dealt with people on their worst days – I was just talking to someone the other day, there was somebody who was working at the national park and was under investigation for misuse of travel funds and it’s somebody I’d known a long time. So there was no joy in putting that in the newspaper … but that person’s still my friend to this day. And that ability to say, ‘Look I had a job to do, I didn’t take any joy in it, and also I didn’t revel in your misfortune.’ … When I first started the newspaper business they had just started doing Police Beat.

Jenn: Oh really?

Earl: And for years, the Shea family, they didn’t write about the police news and they certainly didn’t put names of people who got tickets in the paper, or the court news in the paper. And that was something that [changed] and there was a lot of pushback on that from the bad guys, there was a lot of intimidation. In those early years I had my tires slashed, I had the windows smashed out on my car and the camera stolen, I had my garden shed … set on fire.

Jenn: Oh my God!

Earl: The editor before me had kerosene poured down her well. It was a little more of the wild west in that respect. I went to a chamber of commerce meeting one night, came out and had four flat tires – two shingle nails in each of the four tires. … We had our windows BB’d on the office, bag of cat shit on the steps and the lock was spiked with a nail so you couldn’t get your key in the lock one morning when I showed up for work. And then the tires … .

Jenn: Wow, it sounds like, well I kind of knew, but you see a side of the island that I’m pretty insulated from.

Earl: Well, I think as editor, you have to be able to go out on some billionaire’s yacht and have dinner with him and then you’ve got to be able to go down to the pier and talk with the fishermen. And luckily when my uncle retired from the Navy, he and my grandfather built a boat and they went lobstering down in Muscongus Bay and I used to go with them, so I’m familiar with lobstering – I’m not familiar with billionaire finance, but … that was one thing people had said when I left the newspaper. They said, ‘Earl … you don’t think you’re going to get asked out on billionaires’ yachts if you’re not editor of the paper’ … . I said, ‘Maybe I’m okay with that.’ That’s not what I live for, but to be effective and for your institution to be effective you need to be able to move in all those circles comfortably. … And so some weeks you get a coffee-stained place mat [with] Stevie Smith’s chicken-scratch for a letter to the editor, and the next one would be from David Rockefeller, so you don’t know.

Jenn: No.

Earl: And that’s something you get on this island you don’t get anywhere else. I really think the socio-economic brackets mingle and mix here more than almost anyplace else, a lot of those artificial distinctions, those institutions like separate clubs and separate organizations, they’re not as stratified as other places. I don’t know if you’ve felt that way.

Jenn: … I think that people are very aware of the class distinctions, they’re very aware that they’re mixing.

Earl: Yeah, yeah you’re right.

Jenn: But they still mix.

…

Earl: … Some of the, we call it ‘older money, ‘that I got to know, when they come up to the island they’d just as soon get ahold of everybody they know from the island and hang out with them. They’re not into the whole every-other-night blue blazer cocktail scene. I noticed that you’ve given talks at the Northeast Harbor Library before and whether you’re done or not, they’re out of there at seven because they’ve got a party to go to.

Jenn: Yup.

Earl: You know, this is their ‘what I do before the cocktail party’ and boom, at seven, they don’t want to be late and they’re out. … And that’s okay, but when I worked for Tris Colket, before he had his stroke, of course, he belonged to the fire department and he had a turnout here and his boots and his coat and his helmet in his vehicle and if he was there at his house and the fire was called in, he went and fought the fire. I was pretty impressed by that – why does a guy with that much wealth care? And he and Ruth always cared about the community.

Jenn: Yeah.

Earl: At the same time – this illustrates that little dichotomy a little bit – my friend Lisa … bought this rowboat and we spent the summer painting it and cleaning it up. It was like a 10 or 12 foot rowboat; we kept it at the town pier and we’d just go row around the harbor or go out to Sheep Porcupine or something. So we’re out rowing around one day and Tris comes in on, he had this 28 foot Bertram with a flying bridge and all this stuff.

Jenn: Yeah.

Earl: So he’s coming into Frenchman’s Bay Water Company to get some fuel. And he’s coming in the channel there and he sees me and he starts waving and he yells, ‘Hey Earl!’ And I was like, ‘Hey Tris, how are you doing?’ And then he gestures to the harbor and says, ‘Which one’s yours?’ Naturally assuming we’re in a rowboat because we’re rowing out to a bigger boat.

Jenn: Right.

Earl: And I just looked at him and I said, ‘This is it, and it’s hers!’

Jenn: That’s awesome.

Digression: Me being me, I went looking for some of the articles Earl talked about, hoping for some photos to illustrate this post. Turns out the Bar Harbor Times has been digitized up through 1968, but from 1968 to the present, it’s on microfilm. Have you ever used a microfilm reader? I’d almost forgotten what a pain in the butt research used to be before the internet. Just in case you’re one of those people who thinks things were better in the past, let me walk you through this:

You have a spool of film, on which are images of each page of the paper. You put it on the spindle at left, thread it through the machine to the other spool, and then turn the knob at far right to make it scroll.

The blue and grey gears are for enlarging and focusing. (It doesn’t focus very well because the machine is pretty much an antique, nobody makes parts for these anymore, and the library has to trawl eBay looking for used parts to repair it, so it is what it is.) There’s no index, so if you don’t know the date of an article, you have to scroll through every page of the newspaper for the whole year in which you think it might have appeared. I started out hunting for the cartoon Earl is going to mention soon, which must have been published in 1986 or 1987, so I started with a reel of papers from November 1986 through May 1987. Never found the cartoon, although I did find a photo of the protest he talks about, but after two hours I discovered that if you get impatient and scroll too fast you can make yourself seasick. So yeah, no articles to illustrate this post. Sorry, there are limits to my obsessiveness. Next time I’ll try the attic where they have bound copies of the paper.

Earl: One of the things, in talking with folks in the National Park, too, is trying to get them to understand that the people that live here do have a different relationship [from] the traveling public to the Park. We feel a greater sense of ownership because that’s … our backyard, that’s the only place we have to go. Downtown Bar Harbor’s surrounded by ocean and Park. There is a greater sense of ownership and a greater sense of concern when rules change or fees get imposed or any of that kind of stuff just because it’s a larger portion of our lives than it is for everybody else. … It’s funny when the entrance fees were first imposed, five dollars per car per week, Gerry Paradis was the President of the Chamber or Commerce and he got up to speak at the meeting where they were talking about the fee, and it was one of the funniest lines I’ve heard ever, he goes “I’ll tell ya one thing … you charge them five bucks, they’re going to want more than rocks and trees.”

Jenn: That’s a good one.

Earl: Woody Woodworth was our cartoonist at the paper then, so we did this cartoon of a ferris wheel on Otter Cliff. But there was a chief ranger then, Norm Dodge, he’s passed away now, and he came up with this genius way to kind of wash the local dissent on the entrance fees. You got a sticker for the whole season back then, [and some locals] could get free stickers. And just like a dump sticker that says Bar Harbor, which announces to the world that you’re a citizen of Bar Harbor [which] is a badge of honor in a small town, … those Acadia stickers [showed you were connected.] They gave them to every volunteer fire fighter, every volunteer in the park, every municipal official, they gave everyone that worked at the newspaper one in case we needed to run out for something, including the receptionist and the drivers. So if you couldn’t get one of those free stickers, you were as unconnected as you were. And they did that for years, and basically it took the critical mass of people that would complain about the entrance fees, and silenced it. It was 10 years before they stopped doing that because it was really getting out of hand, they were giving out a thousand stickers.

Jenn: When did they stop doing that?

Earl: It was a couple years after Norm left so it’s probably been 10 years ago now.

Jenn: I don’t remember the free stickers, I guess I wasn’t connected back then.

Earl: Yeah, you could buy a sticker.

Jenn: I did buy a sticker. I always buy my park pass.

Earl: Norm had this spreadsheet of who could get it or who couldn’t get it and you’d just have to go to the ranger station there and get your sticker. Or like for the paper, we had 14 people on our list and they would just give us the 14 stickers and we’d pass them out every year. I think Chamber of Commerce members got [them], everybody that could possibly be in a position to drive in, you got a free sticker.

Jenn: That’s awesome.

Earl: Yeah.

Jenn: I was a good doobie, I just paid my 10 or 20 bucks whatever it was. It always seemed [reasonable], it’s still what like 40, I think for the year?

Earl: It’s up to 50 for the year now, but again it’s an acknowledgment to the local folks – that half price sale that they do. For [the Pajama Sale], and they do it for Midnight Madness, and they do it for the whole month of December. They don’t do that in other parks, that is something that Acadia does and the regional hasn’t cracked down on that. And to me, that’s a heartwarming acknowledgement that there is a special relationship between the towns and the Park here and that they’re basically saying you don’t have an excuse not to get a pass.

Jenn: Yeah, and that’s how I feel.

…

“Park Protest,” The Bar Harbor Times, Thursday, May 7, 1987. The only relevant article I found on the dratted microfilm.

Earl: So Norm Dodge was quite the character, the chief ranger. They were going to install the entrance booth down at Sand Beach to start taking the fees, and a guy named Milan Tait from Bucksport took out a permit for a protest march to protest the booth and the fees in Acadia and all this kind of stuff. He estimated 2,000 people, so the plan was they were going to march from the ball field in Bar Harbor out Schooner Head Road to the Park. And then TV cameras were going to show up and they’d have all this to say in front of the tollbooth. Well they had advertised they were going to do this march. Norm was in charge of installing the tollbooth and this first one was just this prefabricated thing you sat on a slab. So Norm scheduled the installation for two days after the protest so they wouldn’t have anything to stand in front of. I went down there and I’m waiting for the protest march, … [a local guy] shows up on his motorcycle and goes up in the trees and goes through the leaves and he pulls out this chaise lounge, and he sits there like this, he’s waiting for the excitement to start.

Jenn: Uh huh.

Earl: And then he fishes around in the leaves right next to it, and there was a beer that he’d hidden the night before so he pops open the beer, and he’s having a beer and all of the sudden this van pulls up and Milan Tait, two people in their 80’s and two kids get out.

Jenn: Oh my gosh.

Earl: They realized that [no one was] going to walk all that far from the Athletic Field, so they just drove down in the minivan and then they stood there looking around, there was nothing to stand in front of and they just went away. It was pretty funny. … But [that local guy] was waiting for the excitement, he had stashed that stuff the night before, so I thought that was pretty good.

Jenn: 2,000 people.

Earl: Yeah. Well so I went down thinking if they got 200 it’d still be a picture but …

Jenn: It’s hard to get people to show up.

Earl: Yeah, how did the vigil [go] last night, did people go to that? [Ed.note: memorial vigil for the Oct.1 shooting in Las Vegas.]

Jenn: Yeah, we had about 25 people.

Earl: Oh nice. You know, I’ve been a newsman forever and I shut the TV off yesterday morning, I just couldn’t watch it anymore.

Jenn: I stopped looking at updates around noon.

Earl: It’s like crack cocaine or pulling a lever on a slot machine, you keep watching, hoping for one new fact, one new fact that’s either going to be some good news or one new fact that says why, and that doesn’t happen.

…

Jenn: You know what really got to me, is they showed aerial photos and like the hotel is here and the place where the people were, it was so far away.

Earl: Yeah.

Jenn: I’m like what? That’s a military weapon, why is it civilian hands?

Earl: Yeah.

Jenn: Why are those even available?

Earl: Yeah, I don’t disagree.

Jenn: That’s not self defense, that’s not hunting.

Earl: Yeah, I’m a guy and I own firearms, … and I have friends that own weapons like that and it’s almost like a ‘snicker snicker,’ getting away with something to have one. And you can go on the internet and for 50 bucks buy a kit to turn it to full automatic and do it yourself. … I just don’t understand that, I don’t know why there isn’t an NRA for responsible gun owners, that’s not so rabid.

Jenn: Yeah.

Earl: And that’s another example of why we’ve got to get the money out of politics, it doesn’t matter whether it’s healthcare or whether it’s guns. Somebody, I think it was Colbert, pointed out, ‘Hey look why is it that this guy has a right to have all those guns but for the 500 people that were wounded, getting treated in a hospital is a privilege?’ … That was one of the reasons I left journalism – running a newspaper you have to sort of stand in the middle of the street and say, ‘You guys got good points, [and] you’ve got good points.’ And the more I’m standing there I’m like, ‘No they don’t.’ I’m tired of it and I’m tired of having to do middle of the road because there’s some really clear black and white, right and wrong here. … The whole thing now is, ‘Now is not the time to politicize guns or talk about gun control.’

Jenn: And yes it is, this is exactly the time.

Earl: Yeah well, a plane crashes, we talk about aircraft safety.

Jenn: Yes.

Earl: A bridge collapses, we talk about bridge safety.

Jenn: Mm-hmm.

Earl: 59 people get killed and 500 injured by guns, ‘Now is not the time to talk about gun safety.’

…

Carl Roger Brechlin. Photo from the Moose River Camping Club website

Earl: My twin brother passed away several years ago, and to honor and him and his son who had committed suicide a few years before that, [we] had these coins made up. … You can have that one. I have more, so I give them to people.

Jenn: Oh, thank you.

Earl: Yeah, so … it commemorates Carl – he always loved the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. And he lived at 42 Sandy Lane so that’s the 42, and then the star was for his son. And so anyway, what we do is if you’re on a hike or on the Appalachian Trail or you’re up in the Park or Baxter, you leave one of those coins in kind of an inconspicuous spot and then people come along and find them. And then they take them home and they look it up [online] and there’s a legend of the coin and what they represent and then there’s a link to his obituary so you can read about his life. So anyway …

Jenn: All right, so I’ll have to find a good place to leave this.

Earl: … They’ve been all over the world, they’ve been to Machu Picchu, they’ve been to Ayers Rock in Australia, they’ve been to Antarctica, they’ve been to Tahiti, they’ve been all over the United States, every national park. They’ve been to the highest mountain in Kosovo, they’ve been to Stonehenge. And people take pictures of the coins.

Jenn: Oh cool.

Earl: Carl ran an auction house in Connecticut … so the whole idea was that we would keep putting these coins out … until the day that one day came back in a box of stuff to be sold at the auction.

Jenn: Oh no way! Did it come back?

Earl: It did. … It took eight years and this spring … – my nephew runs the family auction house now – a couple from New Haven came in [with] a box lot of coins and right on top of it was one of those. And Ryan went to them and said, ‘Don’t goof on me,’ because they’re people he’s done business with before. And they said, ‘No, we bought it out of a house … down in Stanford or something,’ and so that was the whole idea, the full cycle of life and the full cycle of material goods and everything else. So we’re still putting them out but the prophecy has been fulfilled …

Jenn: Closing the circle.

Earl: It’s also a way for the people that have come before you to salute the people that come after. … People pick it up and take it, you don’t consider it litter.

Jenn: Yeah, it’s got a nice heft to it.

The Moose River Camping Club logo.

Earl: Yeah. … Now Carl passed away in Harper’s Ferry on a rafting trip with a bunch of us – just had a blood clot went to his brain and he was gone. They said [even] had it happened in the emergency room they couldn’t have saved him. So anyway, what was ironic was, about four years after we started this, I got an email from a woman in Portland who’s head of the main Appalachian Trail club …, saying that one hiker had shown one of those to a steward at one of the lean-to’s and they notified headquarters and she wanted to say while that was a great promotional item for our camping club, it was littering and we were not to put those out on the Appalachian Trail.

Jenn: Oh no.

Earl: And so I put on the website, ‘Don’t leave these on the Appalachian Trail;’ now people leave tons of them on the Appalachian Trail because they feel like they’re sticking it to the man … . We had started a group we called the Moose River Camping Club 30 years ago and … we do a backpacking trip and a canoe trip every year, the same group of guys and family and everything. And so that’s what the MRCC stands for.

Jenn: I think it’s a beautiful idea.

Earl: And the irony was, I don’t know how many people I know in the National Park Service [who] had taken them all over the world and left them. And they didn’t see a problem with it.

Jenn: Yeah. Well I guess when you’re in charge you have to be a little more …

Earl: Yeah that’s true, and that’s fine and I don’t want to stick it in their face, but [if] you look up littering in the dictionary it says, ‘To discard something of no value.’ … And it’s like well, those have value because people pick them up and take them so obviously they value them. I put one on Nesuntabunt Mountain in the middle of the 100 Mile Wilderness on the [Appalachian Trail] here in Maine when I was on a hike … four or five years ago. About two weeks later I got an email from a man in Quebec – he and his daughter hadn’t spoken for years and they decided to go on a trip in the 100 Miles to … patch their relationship up. … It was a hot day and they got up to the top of the mountain and they found the coin and he said, ‘It’s become a marvelous memento of our getting back together.’ Can’t argue with that.

Jenn: Sounds like a little bit of magic.

Earl: It is a little bit of magic. So they didn’t see that as littering.

Jenn: No. I think there’s a difference between littering and leaving something deliberately for the next person.

Earl: Yeah it’s like leaving a note. … You look in the lean-tos on the trail and there’s registers where people leave notes and say ‘Hey anybody seen Corn Dog’ or whatever Appalachian Trail name, or ‘I was here’ and that kind of stuff. It’s the same kind of thing.

Jenn: Yeah. So have you hiked the whole Appalachian Trail?

Earl: No I’ve done pieces of it. I’ve always section-hiked; I’ve done three nights, four days here and there but I haven’t done the whole trail.

Jenn: That’s still pretty cool, I’ve never been on it.

Earl: Yeah, well I’ve done Mahoosuc Notch which is the toughest mile, that’s here in Maine. Then you have the 100 Mile Wilderness – there are roads through there but no stores – so that’s the longest section without resupply on the whole Appalachian Trail. And it’s a great resource, I’ve done parts of Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York, New Hampshire, Vermont, so I’ve done a lot of different sections.

Jenn: Oh, which reminds me, I wanted to ask you, how did you end up becoming a Maine Guide?

Earl: Well we started this group and we were doing all these trips and I would get all the food together and plan a menu for 16 people for five days and do all the cooking and all that stuff and the guys said, ‘You’re really a guide, you ought to just get your guide’s license.’ I was a Boy Scout and always did a lot of camping and stuff so I went through the process and passed the background checks and did the written test and went to the oral boards and got the guide’s license.

Moose River Camping Club excursion to Mooselookmeguntic Lake near Rangeley, 2013.

Earl: I’ve always just been recreational, I haven’t used it for a lot. I’ve taken people on adventures, like taking people on guided snowmobile trips and day hikes and then film producers that are looking for location guides and stuff like that. But I haven’t done it … full time. I’ve wanted to do basic wilderness skills for beginners, and I had talked with the paper company about leasing a spot on the lake that you could canoe to and set up camp for a few days and then teach people mapping, compass, cooking, first aid, woodcraft, those kind of things because I think there’s a lot of people that didn’t learn that as kids. If you’re, say, taking people on Allagash trips, eventually you get a lot of customers that are ‘experience collectors’ – they’ve rafted the Nile and climbed Kilimanjaro – and they want to tell you how to do your job. I want people that are scared that if they don’t do exactly what I say they’re going to die. That’s the kind of people I want to take into the woods. What about you, do you do much camping?

Jenn: Not anymore. I was a Girl Scout, did a lot of camping as a kid, and when our kids were little we did more. We used to go up to Baxter every year, then I started having trouble with my shoulders. I can’t sleep on the ground anymore. I just can’t.

Earl: Yeah.

Jenn: So it’s cabin camping for me.

Earl: Yeah.

Jenn: And when the kids hit high school we couldn’t go away for a weekend anymore – they were so busy! But both Brian and I have been talking about when the kids are out of college we can kind of put the house on hold or the rental part on hold and get a little trailer, do the go-visit-all-the-national-parks-thing.

Earl: … Roxie and I have talked about getting a little 18-footer, nothing real big, and just go for three or four weeks at a time … . I think it’s a fun thing to do. … I may have to get scramming here because I’ve got to work today, is there anything else that you wanted to ask or …

Jenn: No, [but] I was right, you did have some awesome stories.

Earl: Well that’s great, I appreciate the chance to chat.

Jenn: And thank you so much for coming. [Laughing] That sounds so formal. “Thank you for joining me today.”

RESTAURANT REVIEW

In case you were wondering about breakfast at the Asticou Inn, it’s a buffet, and I think it was $15. The pastries were great, the potatoes were very good, the eggs were pretty darn good for a buffet, the bacon was kind of limp, and the coffee was good. No popovers at breakfast, though, phooey.

WORKS CITED

Adams, Douglas. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. New York: Harmony Books, 1980.

“Park Protest,” The Bar Harbor Times, May 7, 1987.